Author David Searcy Moves From Horror To Pondering The Mysteries Of The Universe

ArtandSeek.net January 5, 2016 64

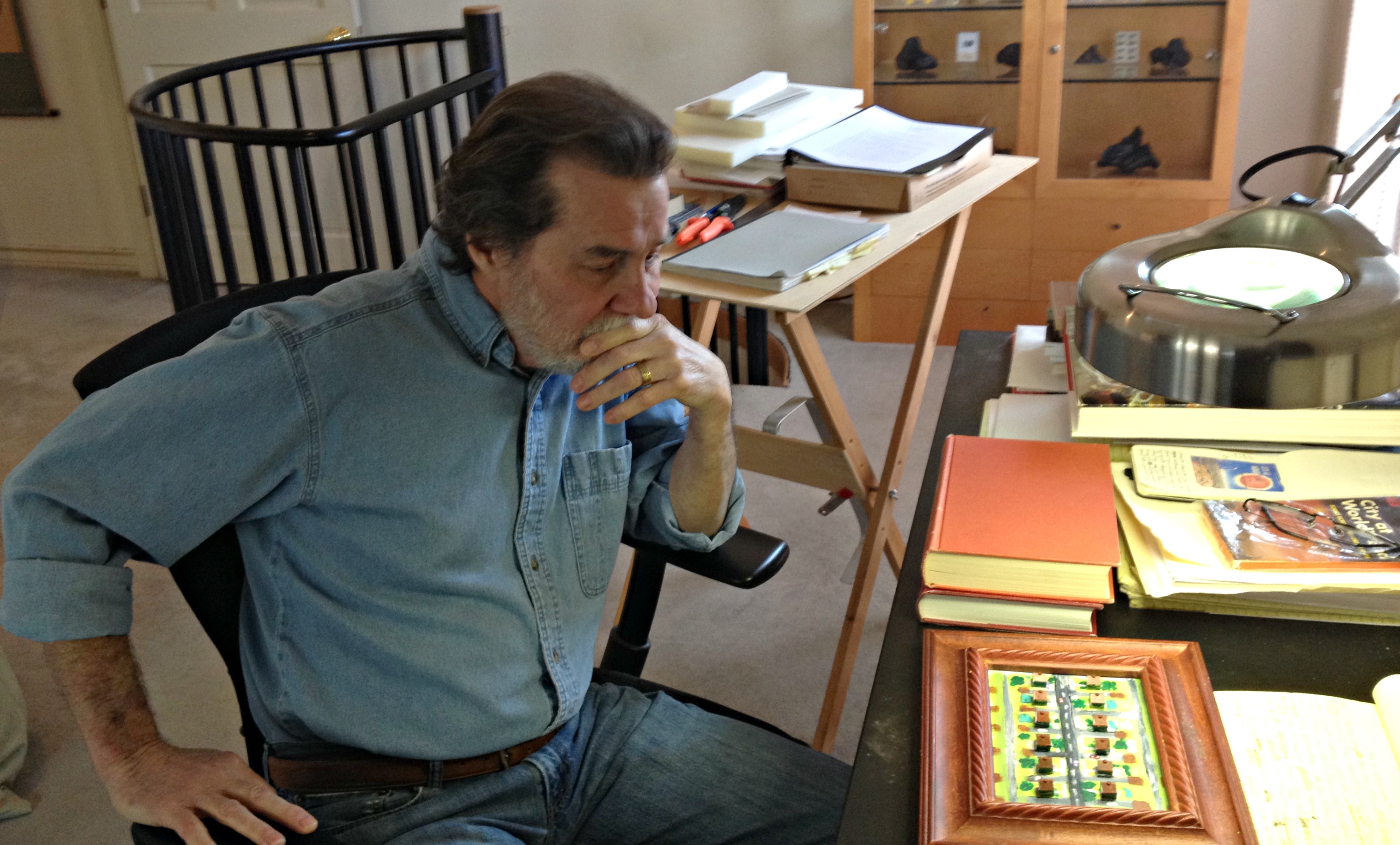

David Searcy at his writing desk. He contemplates a miniature of Dallas real estate cosmology, artist unknown. Above, he fiddles with one of his neat-o, retro-futurist, non-functioning, pseudo-scientific contraptions, attempting to contact Mars. All photos: Jerome Weeks

Fifteen years ago, Dallas author David Searcy debuted with two acclaimed horror novels, ‘Ordinary Horror’ and ‘Last Things.’ But they didn’t sell particularly well. Now, with a new book released this week, Searcy has transformed himself into an essayist, the kind who gets published in ‘The Paris Review’ and ‘Esquire.’ KERA’s Jerome Weeks asks, what happened?

So what did happen? I ask David Searcy

“Well, um, a couple of unpublished novels were in-between there.”

There’s just a little bit more to it than that.

To get to David Searcy’s writing studio in his home, you can take one of three paths. With clanging footsteps, we go up the metal, spiral stairway on the outside of his North Dallas house — a set of stairs Searcy jokingly calls “The Staircase of Sorrow.” (The others are “The Staircase of Wisdom” and “The — actually, he’s not sure which is which anymore.)

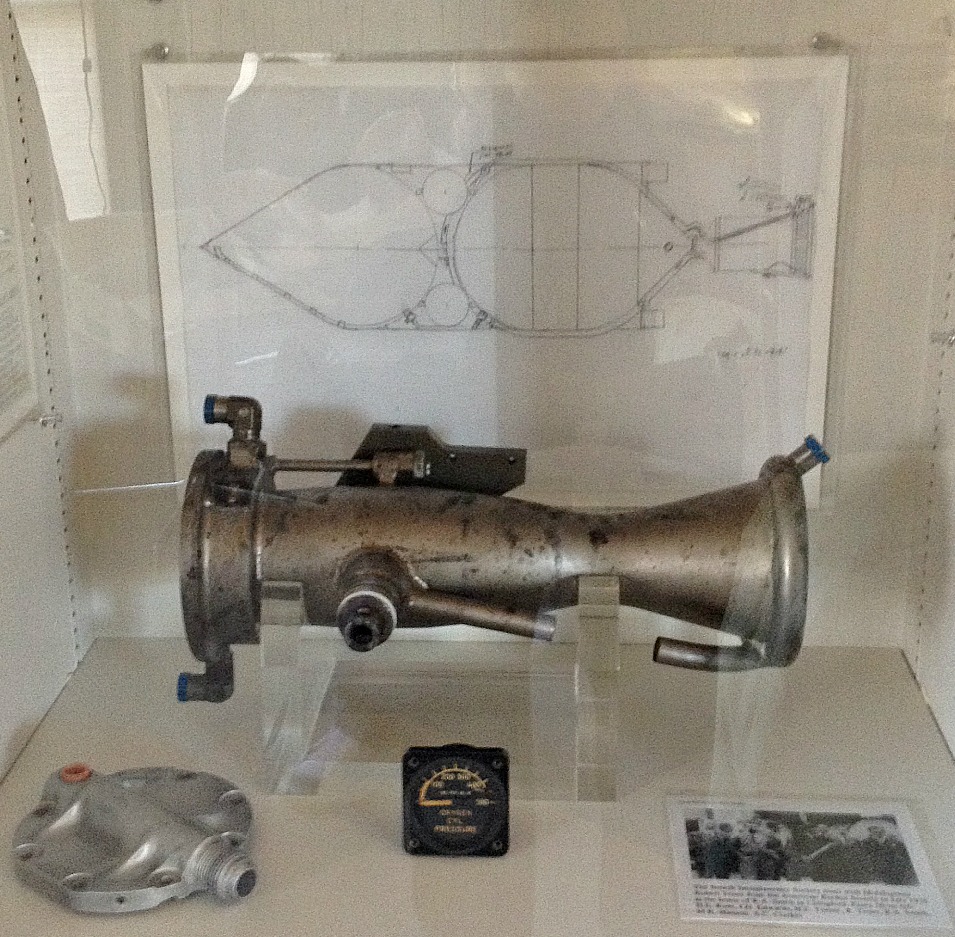

Inside the studio, the visitor is struck by all the orderly, professional-quality displays, glass cases full of small meteorites and huge insects or the flat-file drawers to lay out maps, canvases and blueprints. The place is like a small wunderkammer or chambre des merveilles — a room of wonders. Around the studio, there are Japanese scrolls, sketches of Mars, a gas-powered model airplane and an old rocket engine the size of a microwave — it was built in the ’80s by Robert Truax, an early pioneer in low-cost space travel. Meanwhile, on the writing desk — on his writing desk — Searcy has laid out knives, shears, a hammer and a drill. It’s best, he explains, when he’s both writing and building a little side project, like some jewelry.

The Truax rocket combustion chamber.

Basically, the 69-year-old author has a writing studio that’s like the workshop fantasy of an eight-year-old boy.

“I call it ‘the clubhouse’ sometimes,” he says with a laugh, “surrounded by my idiotic toys.”

All this stuff actually feeds into Searcy’s essays, collected in his new book, ‘Shame and Wonder.’

In fact, the clubhouse kind of resembles a Searcy essay. A typical Searcy essay is an odd, fascinating pile of stuff that he’s stumbled across, picked over, reconsidered, polished up. A Searcy essay doesn’t follow a linear argument. It ruminates; it ponders. It begins with the ostensible subject – baseball, paper airplanes, an artist-friend who owned a fraternal hall in Corsicana – then it wanders off to Enchanted Rock, Hindu rituals or the story of a one-legged tightrope walker crushed by the cast-iron stove he was carrying. It’s often clear Searcy is feeling in the dark for what he needs to make sense of things — the human condition, it would appear. He’ll spend eight amusing pages just deciphering the signs and implications in an ‘Uncle Scrooge’ comic book from 1954. This is a hunt for meaning — driven by the not-so-secret fear that real meaning will never be found; or it’ll be disappointing. Or dangerous. Or it’ll have to be manufactured somehow.

By the end of a Searcy essay, he and his readers are often left blinking in the bright daylight, puzzling over where do we go now? Or why is so much of human life so… marvelously mysterious?

“It’s because it’s a bloody mystery,” Searcy declares. “It’s also a mystery why it should be a mystery. We should take ourselves for granted. We are all we have. How can we find ourselves mysterious? Maybe like in ‘The Princess Bride,’ the word ‘inconceivable’ – ‘maybe we do not know what that word means,’” Searcy says, imitating Inigo Montoya.

“It’s because it’s a bloody mystery,” Searcy declares. “It’s also a mystery why it should be a mystery. We should take ourselves for granted. We are all we have. How can we find ourselves mysterious? Maybe like in ‘The Princess Bride,’ the word ‘inconceivable’ – ‘maybe we do not know what that word means,’” Searcy says, imitating Inigo Montoya.

“There is something to figure out about almost everything. Nothing is what you think it is.”

Searcy can find fear in the placid, grid-like layout of your standard Dallas neighborhood. All the streets and real-estate plots extending into the distance are our feeble attempt to impart order on this vast and violent cosmos. Or just on this vast and empty North Texas prairie. Searcy’s first two novels were what publishers call ‘literary horror’ (he prefers the less pretentious term, “scary stories”). His novels didn’t have bloodshed or monsters; they were more concerned with dread and the unknowable, and as a result, your ordinary horror fan was not happy. His next two attempts at novels stubbornly moved even more into the literary arena – and publishers and editors were not happy.

“I’m proud of him for his sheer endurance,” says Ben Fountain. Fountain is a friend of Searcy; they live only a five-minute walk from each other, across the tollway. Fountain’s acclaimed first novel, ‘Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,’ is currently being made into a film. Fountain says Searcy stuck to his writing, stuck to his own creative intuition, even in the face of rotten luck.

“His agent left the business; his editor left the business. And so he wandered in the wilderness for over a decade. Throughout that time, he just kept writing. And I think that’s part of being a pro. You put down your head and work.”

It was Fountain who gave Searcy’s first two essays to an editor at the esteemed literary journal, ‘The Paris Review.’ And that got the ball rolling for Searcy’s new career as an essayist. The first essay in ‘Shame and Wonder’ — ‘The Hudson River School’ — was his breakthrough, Searcy says. It’s likely to become a Texas non-fiction classic. While sitting in her chair with his mouth open, his dental hygienist told him about her father, a West Texas sheep rancher. He’d been battling a cunning old coyote that had been killing his lambs every year. The rancher settled on one last trick: As a lure, he’d use an old recording of his infant daughter crying.

Searcy tried to craft this macabre little allegory into a piece of fiction, but it never worked. Then he says he gave up, let go of control, opened his mind to whatever possibilities might be out there – and realized that telling how he got that story was his story. Or as Fountain puts it, many essays ask and answer questions. Searcy’s essays ask, What is the question we need to ask?

David, Rocky and the backyard observatory.

“As soon as you start telling a story-within-a-story,” Searcy says, “then telling the story instantly becomes the story. And that just kind of opened me up. And I’m still sitting in the dental hygienist’s chair in a sense, and I’m still trying to maintain that sense of openness.

And silliness.”

He wants to avoid sounding pompous, he says. He has no authority in asking these questions, following these trails. He compares himself to Elmer Fudd — “wabbit twacks!” — following his own footsteps around and around.

The undercutting silliness in ‘Shame and Wonder’ is occasionally provided by the young David Searcy — who, to be honest, isn’t that different from the older one, the one who collects antique Buck Rogers toy ray guns and built his own backyard observatory with a six-inch refracting telescope. Younger Searcy appears in the essays as a befuddled kid, madly in love with outer space and sci-fi movies. He never fully grasps science or, really, the adult world in general. He just loves the look of all the gizmos: the oscilloscopes, the seismometers and whatever that was Peter Graves used for interplanetary communication in ‘Red Planet Mars.’ Young Searcy was the kind of kid who built a clumsy, glue-and-cardboard rocket. In cargo-cult-like fashion, he believed that if he just got the aesthetics right, the rest would follow. The magic would happen. The gods would be pleased. The rocket would achieve lift-off.

Isn’t that how it works? So he lit it up.

“It looked really cool!” Searcy insists. “Just before it melted. Just before it melted — that’s the moment! The extraordinary moment before failure.”

Searcy laughs. His book’s title is held in that dud attempt at a sub-orbital flight. “There’s your shame,” he declares. “There’s your wonder.”