Review: ‘Masque Of The Red Death’

ArtandSeek.net April 16, 2016 55A ballet adaptation of a horror story premiered at the Majestic Theatre last week. The creative people involved – the composer, the dance company, the video artists, the conductor and orchestra – they were all from North Texas, making this a remarkable collaboration. Art & Seek’s Jerome Weeks sat down with KERA’s All Things Considered host Justin Martin – and told him the ballet was definitely not what he expected.

Justin: So Jerome, what are we listening to?

You remember the story?

Yeah, it’s about the plague.

Fact is, Poe’s horror fantasies were not that original. He invented the detective story — a great invention — but when it came to the gothic, many of the traditional items — the imperious aristocrat, the gloomy castle, the antique setting somewhere in Europe, the madness, the supernatural, the blood – these were already pretty familiar when Poe took them on. The gothic novel — ‘The Castle of Otranto,’ ‘The Monk,’ ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho,’ ‘Frankenstein’ — had already come and gone the generation before and wouldn’t be revived until ‘Dracula.’

What Poe did that was original was create the gothic short story. The short story is pretty much an American form, and Poe was its first master, its first great theorist. But the gothic in general — he didn’t add much that was truly fresh.

You probably don’t even like the gothic.

Buttressed by all these prejudices, I feared this new ballet was going to be both gothy-gothic (black leather! steam-punk tutus! scowly make-up!) and rather static (interminable posing!).

And … it wasn’t?

But — back to the gothic.

When it comes to eroticism, Poe’s single use of the words ‘wanton’ and ‘barbaric’ is about as sexually explicit as he gets in this story. But all the convoluted decoration and costuming he loves to hint at certainly suggests sexual frustration and kink: “There was much of the beautiful, much of the wanton, much of the bizarre, something of the terrible, and not a little of that which might have excited disgust.”

So an inclusion of an erotic battle of the sexes in the ballet isn’t farfetched at all. Even so, the overall effect of the costuming, the choreography, the video imagery, was actually to pale and chill out Poe’s overheated prose. Revealing choice: Give most production designers Poe’s setting (and title) with all of its chromatic imagery (every room in the prince’s abbey is color-coordinated), they’d drench the show with the full spectrum of sensual, shocking colors. Not here. The lighting changed hues and the video images certainly had their splashes of color (like the appropriately red velvet seats of the Majestic), but the costumes were vanilla and several video sequences were more or less white. Color was used sparingly — and when it was, it had all the more impact.

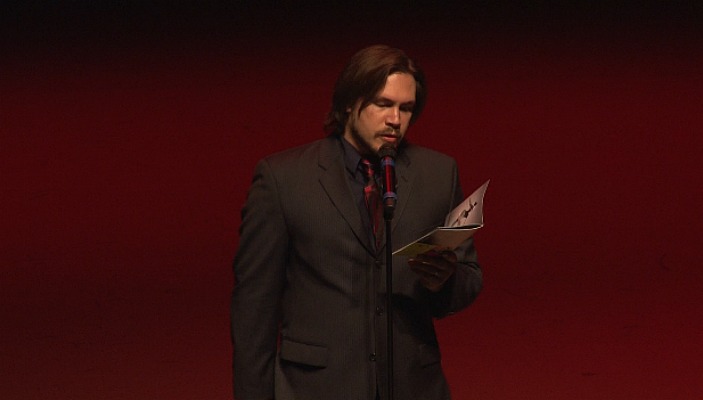

Composer Jordan Kuspa reading Poe’s ‘The Conqueror Worm’ before the performance of ‘Masque of the Red Death.’

Wait. All this doesn’t sound like a horror story.

What’s more, adapting ‘Masque’ into a ballet is perfectly fitting: A ‘masque’ isn’t a fancy French term for ‘mask.’ The ‘masque’ was a genre of grand party entertainment in late Renaissance courts. It involved music and theater and stage effects (even whole architectural structures). But what it generally ended with was a dance for the court, including the king and queen, a graceful symbol of monarchical unity and power.

It’s not clear Poe really knew what a ‘masque’ was (they hadn’t been performed in 200 years). Nothing he describes in the prince’s decadent revels really resembles a formal masque. Poe seems to see the word as a shortened form of ‘masquerade,’ the term he uses several times for the prince’s end-of-the-world-fest, which is described in a flourish of glorious but decidedly vague terms: “There were much glare and glitter and piquancy and phantasm … There were arabesque figures with unsuited limbs and appointments. There were delirious fancies such as the madman fashions.”

I’m willing to bet, in fact, that Poe knew the term ‘masque’ almost entirely from Shakespeare. One of the only instances in which Shakespeare includes a masque in a play is ‘The Tempest.’ And the main character in ‘Tempest’ is called, of course, Prospero — the same name as Poe’s prince.

But again, back to the gothic. What really conveyed a foreboding atmosphere in this ‘Masque’ was, one, Kuspa’s music. It was very rich, dark and theatrical – even a little too much like movie music at times. Poe describes Prospero’s abbey having a big, ebony clock, ticking off the hours, so Kuspa includes hammered chimes solemnly marking the time. The music may churn away in the strings and brass, but the chimes would suddenly bring everything to a halt. We move from the grim and frantic to a hushed, sepulchral air. It’s a dramatic gesture borrowed from things like Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique, but you can’t say it still isn’t effective.

And the other feature that added so much to the proceedings was the background video by Jeff Gibbons and Gregory Ruppe. They employed a wide variety of images and scenery — the seaside, people trapped and squeezed into a box — but most effectively, they filmed the Majestic itself. They made the theater into the prince’s abbey – so we in the audience were all trapped inside it with him.

And with death.

That’s smart.

Like the hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s film ‘The Shining’?

And then it all came thundering together at the end. My only criticism? The video was often so compelling, I sometimes lost track of the dancing. This split effect — between visuals and music and movement — reminded me of director Robert Wilson’s brilliant stage works. Wilson has argued that theater has been overwhelmingly text-based, text-dominant. He wants to counterbalance that bias, staking a claim that the visual is just as important as what is spoken. He’s known for giving his collaborators a very free hand with only a very loose framework or general idea to guide them. So, at times. Consequently, it’s as if the different parts of Wilson’s works run on separate tracks, occasionally intersecting, occasionally one side overpassing the other or sometimes fusing together into something greater than the parts — which was what happened here.

Well, what was the ending like? Prospero still died, right?

So what are you looking forward to this next week?