De Palma’s Phantom Returns To The Majestic, Where It Was Shot

ArtandSeek.net June 16, 2016 42Brian De Palma has always directed his own orbit. Best known for “Carrie,” his early films were largely thriller joyrides. They were pulpy things, laced with technical playfulness, composed of the sort of exotic dark matter that left them destined for cult stardom.

Part of what made De Palma different is that he wasn’t afraid to be. He’d do two Hitchcock knock-offs, then try a comedy. And in early ’73, financing and opportunity aligned to let him turn yet another corner and shoot a film he’d been toying with for years: A haunted horror spectacle, set in the key of rock and roll.

Eventually, he’d call it “Phantom of the Paradise.” And he’d find his architectural muse right here, at the Majestic Theater, an old vaudeville hall turned movie house in downtown Dallas.

Now, 42 years later, the Phantom returns to haunt the space, yet again.

The 2016 Oak Cliff Film Fest, running this weekend, focuses on ’70s New Hollywood, a time when young buck directors like Kubrick, Malick, Spielberg and, yes, De Palma, took creative control away from the studios to pump new life into the form.

As a mascot of sorts, De Palma gets saluted twice during the festival’s events: “De Palma,” a new documentary on his work and process, screens Sunday at Texas Theatre, and “Phantom of the Paradise” shows Friday at the Majestic Theater, where the film’s wildest interior scenes were shot.

Leading lady Jessica Harper will even fly in for a rare public appearance to walk its old boards and reminisce.

Jessica Harper auditioning for “Phantom of the Paradise”

Granted, “Phantom’s” plot territory isn’t any newer today than it was when it was released in ‘74. An obsessive, mutilated music composer, in a mask, haunting a music venue is, well, a touch recognizable.

But instead of an organ, our monster plays a Moog modular synthesizer that fills an entire room. (It’s not a purely stylistic prop. Stevie Wonder used the beast of an instrument — known as “TONTO” — on “Songs in the Key of Life” and “Music of my Mind.”) And rather than being born hideously deformed like that other guy, our Phantom gets his face crushed in a record press. There’s also more blood and glitter — You get the idea.

At the TONTO.

However, fans know appropriation is De Palma’s bread and butter. He steals from the sacred cows, like Alfred Hitchcock and Robert Wiene, in order to build a familiar haunted house.

Then, he dismantles it. Installs trap doors. Dangles severed limbs. Employs trick lighting. And captures the entire exquisite collapse in slow motion, split-screen and other slick, stylized slight-of-lens to delight and outfox his audience.

It’s extremely gratifying. And in “Phantom,” he holds nothing back.

When it was originally released, few were fully on board. Even beloved, longtime “Dallas Morning News” film critic Philip Wuntch, who passed away in 2015, seemed to have a special, but often conflicted, connection to the director.

In his 1974 review, Wuntch scolds “ ‘Phantom’ borrows shamelessly from ‘Dr. Faust,’ ‘Picture of Dorian Gray,’ ‘Phantom of the Opera’ and even ‘Psycho.’ There’s an attempted murder in a shower, with the transvestite victim looking remarkably like Janet Leigh.”

And yet, despite De Palma’s…flexibility…with material, Wuntch’s review vacillates between “what is he doing?” and unrivaled appreciation for the director’s complete irreverence.

“’Phantom of the Paradise’ may be accused of many things — including lapses of restraint and consistency,” he writes. “But one vital, all-compensating thing can be said in its favor: ‘Phantom of the Paradise’ never bores.”

Screenshot from “Phantom of the Paradise”

Wuntch goes on with genuine affection, describing the then-shuttered Majestic as it’s captured in the movie. “It’s great to see the grand old theater again, shining and beautiful, with her arabesque staircases and giant auditorium used to strong advantage.”

He’s right that the film is bawdy. And continuity isn’t strong. (There’s one scene where Swan, the evil music mogul, walks into a room wearing one suit, but out in another.)

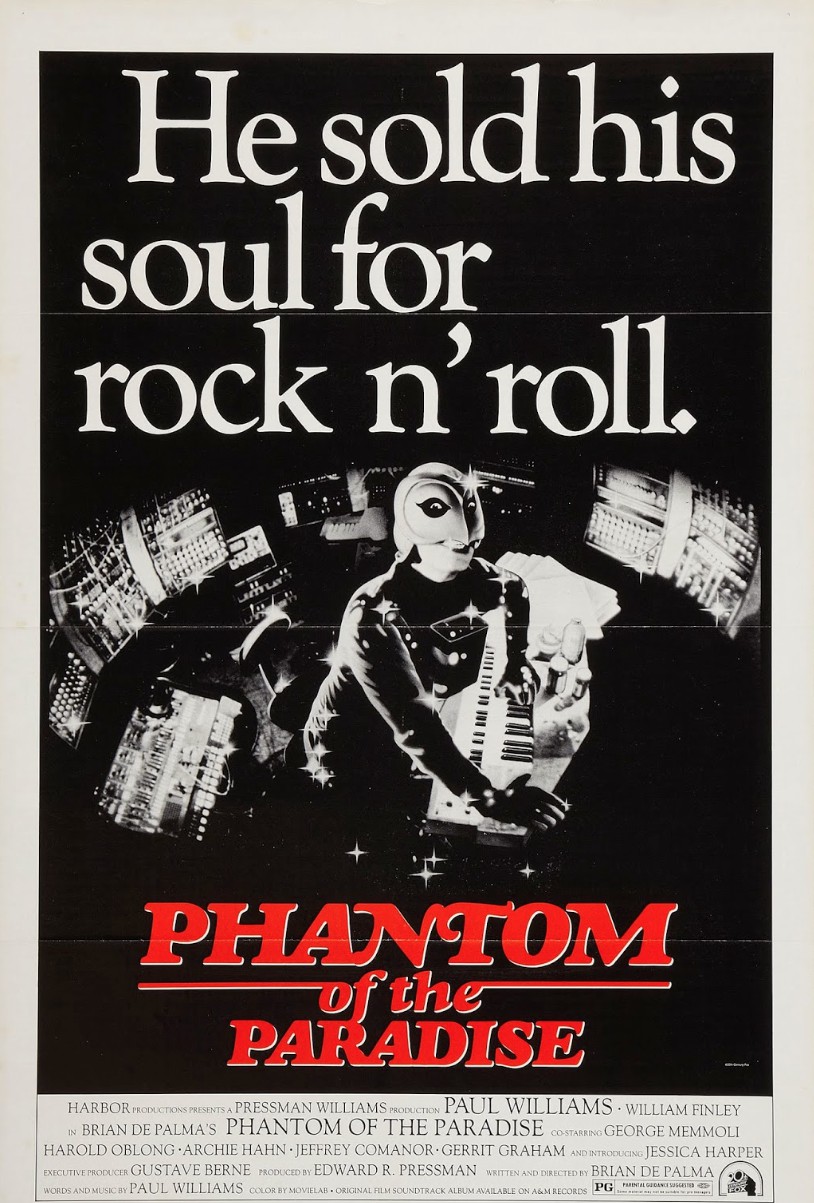

Movie poster.

Wuntch is also spot-on about the theater’s casting as “The Paradise,” the (second) hottest venue the devil ever opened. The old hall is fantastically shot, and “Phantom” serves as the historic venue’s swan song, through a deal brokered after its decline.

De Palma intended to shoot at the Fillmore, but opted out when he saw the auditorium’s blandness. Meanwhile, the still-new Texas Film Commission was busy telling Hollywood about its state’s undiscovered gems.

Soon, everyone got what they wanted. The Majestic found a suitor who appreciated her inherent charm, and De Palma found what he called “…the oldest theatre we could get that has terrific interior design,” in a 1975 interview with David Bartholomew.

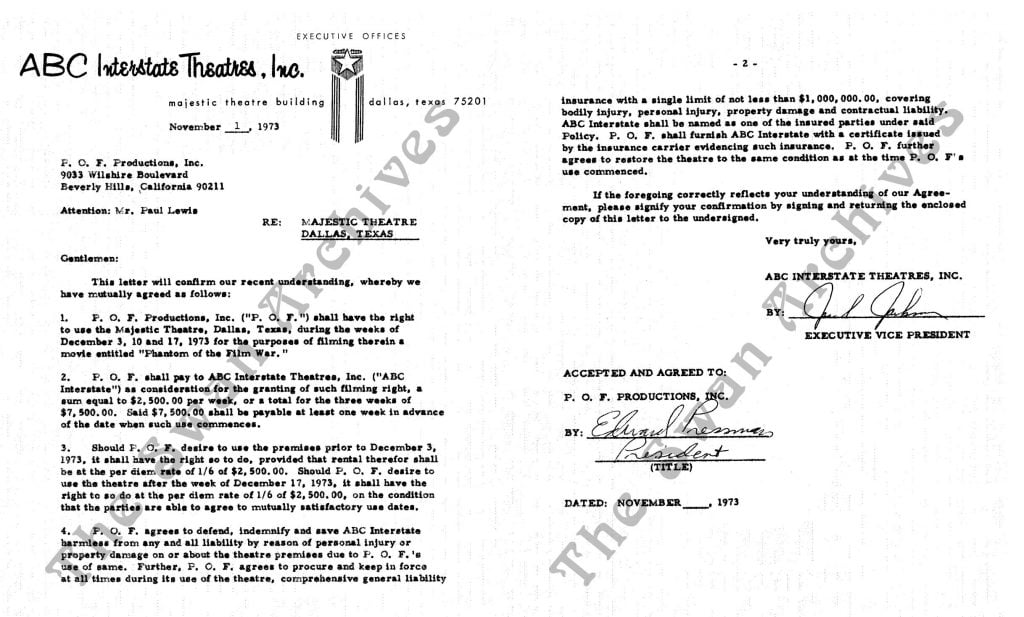

According to an old rental agreement, he got the empty building from ABC Interstate Theatres, Inc. for a song, at just $2,500 a week.

Rental agreement for the Majestic. Photo: Swanarchives.org

With its rich colors, intricate molding, and weighty stage curtains, the Majestic acts as a deliciously feminine foil for Phantom’s set, a pilled-out take on German expressionism and Doctor Caligari. It was designed by Jack Fisk and dressed by his then-girlfriend (now wife), actress Sissy Spacek, who ran errands and decorated scenes as needed. (The pair returned to work with De Palma in “Carrie,” with Spacek in front of the camera.)

In the years that followed, The Majestic’s owners, the Hoblitzelle Foundation, would turn the keys over to the city, which gave it some love, then reopened it as a performance space in ’83. Recently, through a collaboration with Texas Theatre, films have even begun showing there again.

To see the space both then and now, as a sort of environmental split-screen, pop by the “grand old theater” Friday night. And relive the rock opera at the edge of your ever-so-plush seat, because while it may be zany, “Phantom of the Paradise” never bores.

Jamie Laughlin is a freelance writer who covers art and culture topics across North Texas.