Review: The Dallas Theater Center’s Outdoor ‘Electra’

ArtandSeek.net April 21, 2017 38Kevin Moriarty aims to re-ritualize ancient Greek tragedy for digital-age Dallas.

What director wouldn’t? With his ‘free adaptation’ of Sophocles’ ‘Electra,’ the artistic director of the Dallas Theater Center hopes to re-invest the ancient tragedy with the kind of mythic, civic and emotional force it once held. But this is not some trendy, white-box-and-dance-rock revival of Sophocles’ tale of revenge, gods and royal murders. Moriarty took the inventive gamble of staging ‘Electra’ outdoors in the heart of the Arts District – somewhat as the Athenians might have seen it originally at the Theater of Dionysus on the slope of the Acropolis. Moriarty has added modern dress and an electronic update: Audience members wear wireless headphones as we move from site to site in and around Annette Strauss Square. We hear not just the onstage characters; we listen to the spirit of King Agamemnon (Alex Organ) who performs the function, more or less, of the Greek chorus, bemoaning, explicating, beseeching, blessing.

Moriarty sees himself as a ‘big idea’ director, and this entire interactive, city-at-night staging is the kind of large-scale gesture and technical challenge he’s drawn to – akin to turning the Wyly Theatre into a football field for ‘Colossal.’ Or sending theatergoers off in bump-em cars in ‘The Wiz’ to ride along the Yellow Brick Road.

Immersive theater outdoors on this scale is a novel and ambitious experience – probably unique at the moment. Some serious plaudits are in order, then, for the whole daring, striking but yes, sputtering, clunky effort. Moriarty clearly wants to Say Something About the State of Dallas in a Tragic, Ceremonial Form. To give one example: The director reverses the Greek tradition of keeping the violence offstage. Towards the end, he confines the audience inside the Annette Strauss Square’s bunker-like support room, lending the final murders a face-to-face intimacy. We’ve moved from the wide-open amphitheater down into this narrow, utilitarian tunnel to witness some bitter bloodshed. In effect, we’ve gone ‘backstage’ to see what the Greeks never did.

Then we all walk back outside – in single-file – to the Winspear’s reflecting pool to perform a toro nagashi, the Japanese ceremony of floating paper lanterns downstream to help guide ancestral souls to the afterlife. With a cool evening, with people encircling the dark pond and placing (battery-powered) candles on its mirror-flat surface, the entire moment from procession to contemplation makes for an undeniably peaceful, glimmering moment — that is, if you don’t mind being physically herded around by a small army of ushers. And provided you ignore much of what’s being said on the headphones at the moment.

Annette Strauss Square, facing the unfinished 1900 Pearl tower. All photos: Karen Almond.

The fact is it’s difficult to invent a new ritual, a set of meaningful words and gestures that actually have the heart-cracking impact of catharsis. Think of all the balloon-drops at political conventions, all the accompanying punditry and video fireworks intended to exalt and celebrate. These are, indeed, rituals — repeated actions intended to make a statement, mark the occasion as important, connect the moment to the past and extend its impact into our lives. In short, it’s supposed to make these words real. But it’s a rare convergence of rhetoric, events and political leaders when they ever achieve anything remotely like that. Mostly, we roll our eyes or change the channel. Rituals are like re-enacted, collective memories. They embody shared meanings and they transport those meanings from past to present to future. Offhand, I can’t think of any that are battery-powered.

So really, there’s little in our contemporary culture with any narrative so central it could be equivalent to the tragedy of the House of Atreus. Maybe the rise and fall of the Kennedys. Perhaps our Civil War and civil rights struggle. For the Athenians, this was the whole ball of wax, not simply a family brawl re-enacted as entertainment. It was military history and origin myth elevated to national religion, it was ethical philosophy and municipal politics being debated and fought over onstage.

It was, of course, a grimly familiar story. The Trojan War, Part III: The Fallout. When King Agamemnon returned to Mycenae after defeating Troy, his wife Clytemnestra murdered him to live with her lover, the usurper Aegisthus. (Curiously, the program for ‘Electra’ locates us in Argos — which was Aeschylus and Euripedes’ setting for their versions of the story. Every translation of Sophocles’ script I can find locates it in Mycenae.) For years, daughter Electra – the primal resentful teenager – has vowed to avenge her father’s death and now learns her brother Orestes – who everyone thought was dead – has finally come home with retribution on his mind as well.

Sophocles wrote his version in the shadow of Aeschylus’ ‘Oresteia’ trilogy, performed some 40 years earlier and even then considered by the Greeks to be one of their literary monuments. Quite the precedent to go up against. What Sophocles brought to Aeschylus’ story was his famous austerity. He hacked it down but elevated it by focusing on relentlessly driven characters and their fury for justice. He sharpened the stakes, especially in the great face-off between Electra (Abby Siegworth) and Clytemnestra (Sally Nystuen Vahle). Unlike Aeschylus, Sophocles grants Clytemnestra something of a fair case by stressing the king’s killing of their daughter Iphigenia. She reviles her husband for sacrificing her to the goddess Artemis — so the Greek army could finally set sail for Troy. Agamemnon chose his brother’s grievance about losing Helen, plus his own need not to lose face in front of his soldiers — Agamemnon chose these over his daughter’s life.

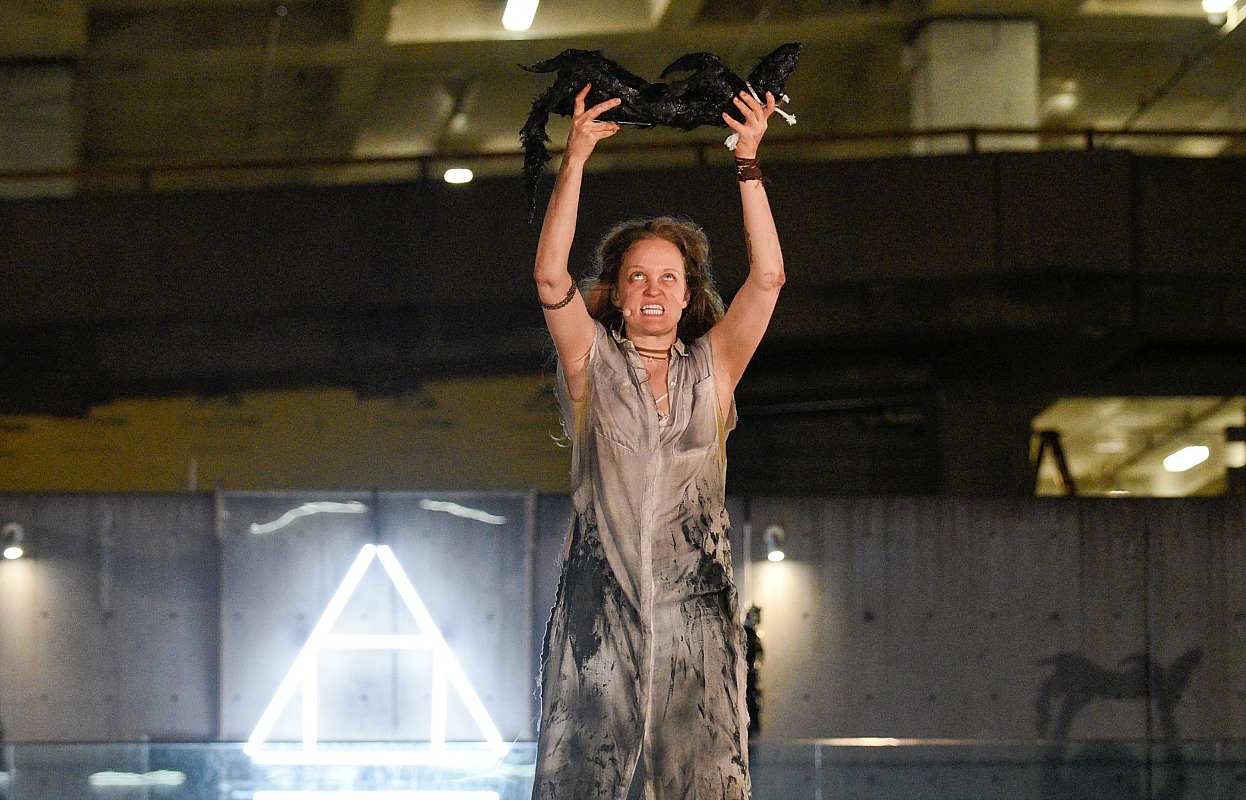

Trust me. She’s really just warming up: Abbey Siegworth as the title character in ‘Electra.’

In effect, it’s much the same choice parents make when we send our children to war: We sacrifice them. This accusation of sacrificial murder gives Clytemnestra more cause for her actions, making her less an adulterous back-stabber. It balances the mother-daughter argument more, tipping it back and forth like a vicious cross-examination. Electra eventually declares outright she’s more than willing to use evil to counteract evil. So – how does one parse out justice from revenge and from family grudges?

But while Moriarty is an ‘idea’ director, he’s not proven himself a particularly effective ‘actor’s director.’ With strong women, he basically sets them on ‘Take No Prisoners, Level 12’ and never has them downshift into anything more subtle. In Moriarty’s torrid, muscular version of ‘Oedipus el Rey,’ Sabina Zuniga Varela (who played Queen Jocasta) at least had the chance to take a break from all her gangland machisma to unveil a needy, lonely, mature woman. In his unattractive but undeniably fierce ‘Medea,’ Sally Nystuen Vahle played the title character as a walking blunt-force trauma.

She does much the same here against Siegworth. Non-stop rage and resentment are wearying to watch and listen to (much less perform), and Sophocles knows this. It’s why his chorus and Electra’s sister Chrysothemis (an appealing Tiana Kaye Johnson) provide (ineffective) voices of caution and common sense. It’s also why some of Siegworth’s best moments come when she suddenly opens up with tender disbelief because Orestes (Yusef Seevers) has seemingly come back from the dead. At last, we all can take a breather. Ditto with the ruse that Paedagogus, Orestes’ loyal servant, spins out about Orestes’ death. All the shouting stops for an action sequence, as actor David Coffee vividly recounts a neck-and-neck chariot race.

But it’s as if all Moriarty can do is try to find new outlets for these characters’ rage: He has Siegworth attack a trash can. OK. So we half-expect her to heave it across the lawn like a professional wrestler. Or stomp on it like a beer can. Instead, she plucks out some crumpled wrappers and strews them in the air. Perhaps Moriarty wants us to see Electra’s long-searing grief as fundamentally childish or ineffectual — because that’s what this looks like: a tantrum.

Orestes (Yusef Seevers) and Paedagogus (David Coffee) at King Agamemnon’s tomb in ‘Electra.’

The director and his actors probably felt the natural impulse to fill up that football-field-sized lawn with some arm-flinging emotions. But the smaller, more enclosed scenes at beginning and end are the effective ones. Brilliantly, Diggie, the scene designer, has created brutalist-concrete walls and white-neon abstractions that evoke Sophocles’ rock-hard style and the sun-baked Mediterranean setting — as well as the Arts District’s own architecture. Diggie’s slabs are as bold and modern as a Louis Kahn masterwork and as primal as an old stone temple — especially in the first scene at Agamemnon’s tomb, which looks as though it was simply trucked over here from the lobby of the Meyerson Symphony Center. Along with Broken Chord’s ominous but restrained underscoring throughout, Diggie’s stark designs make this ‘Electra’ open with a feel of crisp beauty and chilly menace. The music and the set pieces are the strongest, shrewdest elements of the entire production.

Well, and then there’s Dallas itself. With this ‘Electra,’ Moriarty’s main shot at contemporary relevance and civic significance is his fundamental tactic: He uses the entire Strauss Square and the city skyline as his setting. This ancient story is happening right here — right across the street from the valet parking for Stephan Pyles’ Flora Street Cafe.

So let’s consider the city surroundings and what they say, however unintended or ironic. We enter the amphitheater by walking past a small shrine to a local Dallas deity: a white Lexus GS Turbo with the FSport package. It was common for Greek homes to have a small statue of a good-luck god near the entrance. But this is impressive, a display fit for a palace. The car is elevated on a beautifully lit, angled platform, the better for our inspection and adoration. I felt remiss; A bad omen: I’d not brought Lexus-Dionysus an offering.

As we enter the amphitheater, we can see, across Woodall Rogers, the outline and lights of that august American temple, the Federal Reserve Bank. And during the performance, when Electra occasionally shouts a curse to the heavens or in the general direction of her mother’s house, Siegworth seems to aim it at 1900 Pearl, the unfinished tower that looms over the entire drama. It’s a skyscraper that a number of Arts District fans hate for blocking a major view of the Meyerson, for crowding in on Strauss Square’s own expansive airiness, for adding yet another blue-glass, office box to a downtown that doesn’t really need more and for paving over one of the last small bits of green space left in downtown.

I’m not simply having fun mocking things here. I have to believe Moriarty is well aware of how spectacular this view is, what it lends ‘Electra’ with its vast display of urban wealth, commercial vitality and aesthetic sterility. Why else would he go to all the logistical troubles of rain dates and headphones and ushers to stage ‘Electra’ in a location that shouts Here is Dallas in All Its Ambitions?

Tiana Kaye Johnson as the more cautious sister, Chrysothemis.

In David Grene’s translation of ‘Electra,’ Orestes expressly states at his father’s tomb that he’s come to purify and restore his home country. There may be no plague in Mycenae — as there is in Thebes in Sophocles’ ‘Oedipus’ — but Greek tragedies established the trope of opening in a city that’s unwell, troubled, burdened. The palace stands in for the entire city-state, the royals are fateful representatives, the conduits between the gods and ordinary citizens. It’s a metaphor that runs through Shakespeare (“Something’s rotten in the state of Denmark”) to Ibsen, Chekhov and Shaw (“This soul’s prison we call England. She will strike and sink and split”).

But while Moriarity has gone to all this trouble to place ‘Electra’ practically in our town square, I’m not sure what, if anything, he wants to say about the State of Downtown Dallas – other than it makes for a splendid backdrop for a piece of theater. When we come to the final killings that will resolve the House of Atreus for good, Electra dreams of an axe felling a tree. Agamemnon was murdered with an axe, and Aeschylus specifies Orestes uses a battle axe against both Aegisthus (Tyrees Allen) and Clytemnestra. (Indeed, Clytemnestra calls for her own battle-axe to fight her son — way to go, Mom). But staging two axe murders in full view of an audience crowded into a medium-sized room is not an easy bit of fight choreography to pull off convincingly. Limbs need to be lost. Instead, Seevers uses a dagger – which is a little disappointing. All this build-up, all this raging and we get a a couple of minor, back-alley stabbings. But Moriarty seems to want this anti-climactic feel: The evil couple end up as just a pair of corpses, heaped on the ground here, covered by little blood-splattered plastic sheets. Sic semper tyrannis. And as we know, this isn’t the ending-ending. Moriarty has a calmer resolution in mind.

In this scene, a second disappointment comes when, having howled for most of an hour, Siegworth speeds past perhaps the two most blood-curdling words in all of Sophocles. Imagine: As was the tradition, Athenian theatergoers never see Clytemnestra’s slaughter. They see Orestes rush after her, hear her screams offstage, hear the battle axe smash her, hear her cry for pity. “You had none for him nor for his father” Electra says — and watches offstage what the audience can only imagine.

Another scream. Then Electra urges her brother: “Strike – again.”

Now that’s murderous hatred.

I bring up the butchery because it took Aeschylus three full plays to work out all his issues with justifiable regicide and with the Furies, the primordial gods crying for vengeance. Ultimately, he opts in favor of Athens’ trial-by-jury as a divinely ordained solution. Sophocles, on the other hand, sets up the basic moral arithmetic of tragedy in drama after drama: Only bloodshed will expiate, only it will restore order. Don’t look to gods or civic institutions – “blood to answer blood,” as Electra says. Not simple revenge, but sacrifice. In tragedy, the evil are destroyed but the good will suffer (and often die) trying to achieve some modicum of justice. That’s ‘Hamlet.’ That’s ‘Othello.’ That’s ‘The Duchess of Malfi’ and ‘The Crucible.’

And that’s why Sophocles’ ‘Electra’ ends so abruptly, almost like a rebuke to Aeschylus’ extended moral wrestling. The evil king and queen are killed, and David Grene’s translation has the chorus say, ‘O race of Atreus, how many sufferings were yours before you came at last so hard to freedom, perfected by this day’s deed.’

‘Perfected.’ Quite the claim for a screaming double homicide. There’s Sophocles’ austerity for you. That’s it, he declares, This horrid house is cleansed. It’s over.

But Moriarty can’t leave it at such an abrupt, brutal end — so we exit on our candle-lit procession and wend our way to a very different feeling of (attempted) resolution. I couldn’t help but be reminded of the Stations of the Cross on Easter weekend, circling the church and stopping as we hear Jesus has fallen the second time or his face has been wiped.

Instead, we hear Alex Organ explicate the characters’ various futures: what happened to Orestes, what happened to Electra, who got married, who went into real estate. And then we hear his “favorite story” about all this: Iphigenia was never sacrificed by Agamemnon in the first place. (This is, in fact, a variant Greek myth.) The goddess Artemis rescued her and replaced her with a deer.

It’s a lovely thought. But it makes nonsense of what’s preceded it. First, if Iphigenia was never killed and a deer was sacrificed in her stead, then wouldn’t Agamemnon know? Wasn’t he there? Or is this just Agamemnon offering it as a happy notion to make us feel better? If we’re to take this as the Chorus speaking, and not Agamemnon, the deer replacement story still completely undermines one of Clytemnestra’s major justifications for killing her husband. And a major reason Orestes seeks vengeance.

We’re left with a disjointed experience, an ushered promenade around the Winspear, above ground and underground, onstage and off. You don’t get catharsis but who does these days? For what it’s worth, you do get a theatrical experience unlike any other.