A West Dallas Arts Kerfuffle

ArtandSeek.net April 21, 2017 32In West Dallas, a piece of art that reflects on the neighborhood’s controversial housing and development issues has itself caused controversy. The work was commissioned by the city, hung in a city community center and then removed by city officials. Now, the city says it can go back up. Today in State of the Arts, Art&Seek’s weekly look at what’s making news in the North Texas arts scene, we take a look at what can happen when art hits close to home.

When The City of Dallas bolstered housing safety standards last fall, the owner of 300 rental homes in West Dallas said he wouldn’t be able to bring the properties up to code.

Families who had lived in these small homes – some for decades – were told they’d have to move by June. This issue hit home for Dallas artist Angela Faz.

“Yes, so my aunt actually has a home that she’s having to relocate from because the city is cracking down on the landlord,” says Faz. “She has to find another place to go, another place to live.”

Faz’s family lives in West Dallas. Her parents stay in a neighborhood that she says hasn’t been “rediscovered,” but her aunt is obviously facing a different situation.

That’s why she decided to make this housing dispute and the migration of families in West Dallas the focus of her latest work – it’s called “Stories of Displacement, Migration and Resilience.”

“Being a native from West Dallas, I was hoping to get across the fact that there are lots of different changes happening. I sort of wanted to bring awareness to the different changes,” Faz says.

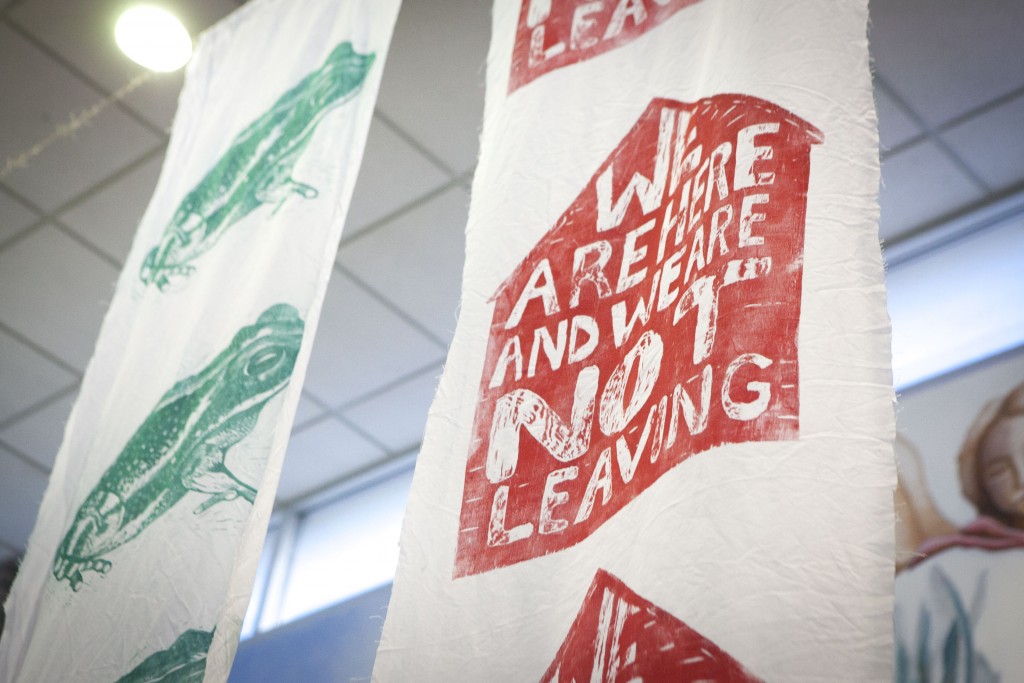

Her work is a series of hand-crafted banners designed to hang from the ceiling at the West Dallas Multipurpose Center, which is run by the city. They feature woodblock prints with messages of migration. One, for example, featured salamanders, which used to be common in the neighborhood.

“People will have to find places to live,” says Faz. “So I was using these animals as a way to kind of tell that story with the hopes of creating empathy for these migratory patterns that are happening.”

Faz didn’t simply rely upon metaphor to explore the development and gentrification of this area. Some of the banners had images of homes and quotes from locals that said things like “We are here and we are not leaving.”

Two weeks ago, those banners were taken down by staff at the Multipurpose Center, which is run by the city housing department. The center’s manager declined to comment. At the time, the city’s Cultural Affairs director Jennifer Scripps said she understood the center had a policy against political displays.

Dallas Office of Cultural Affair Director Jennifer Scripps. Photo: Jerome Weeks

“I certainly honor a city buildings right to remain apolitical,” Scripps says. “If you’re political for one topic or one side of a conversation you open your site up to be political in all manner. And that site is apolitical.”

Scripps said she wasn’t involved in the decision to remove the work. In fact, her office helped pay for it. Faz’s work and several other pieces at the center, and around the city, are part of an art project called Decolonize Dallas. The office of cultural affairs awarded a grant to help fund the project.

Decolonize Dallas organizer, Carol Zou, says the fact that the city funded the work should be reason enough to ensure it has a place to hang on city property.

“It’s called Decolonize Dallas. Its premise is about racial, economic and structural inequality,” says Zou. “But at the same time they’re trying to tell us that expressing something about inequality is too political.”

Zou claims that the city is trying to censor Faz’s work.

“Censorship is when you refuse to show an artwork or an expression of speech, so I think in the sense that the images created by our artist were taken down immediately her images were censored.”

Kali Cohn is a staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union in Dallas and she says it’s not so clear cut.

Cohn says there are lots of things to consider in censorship cases, including how artwork is labeled, how the space where it hangs is normally used and what kind of restrictions the government is attempting to apply. Still, she has concerns.

“Should an artist be compromising in terms of political speech because the government doesn’t like it?” asks Cohn. “You know I think that’s really antithetical to a lot of what we believe about free speech in the United States.”

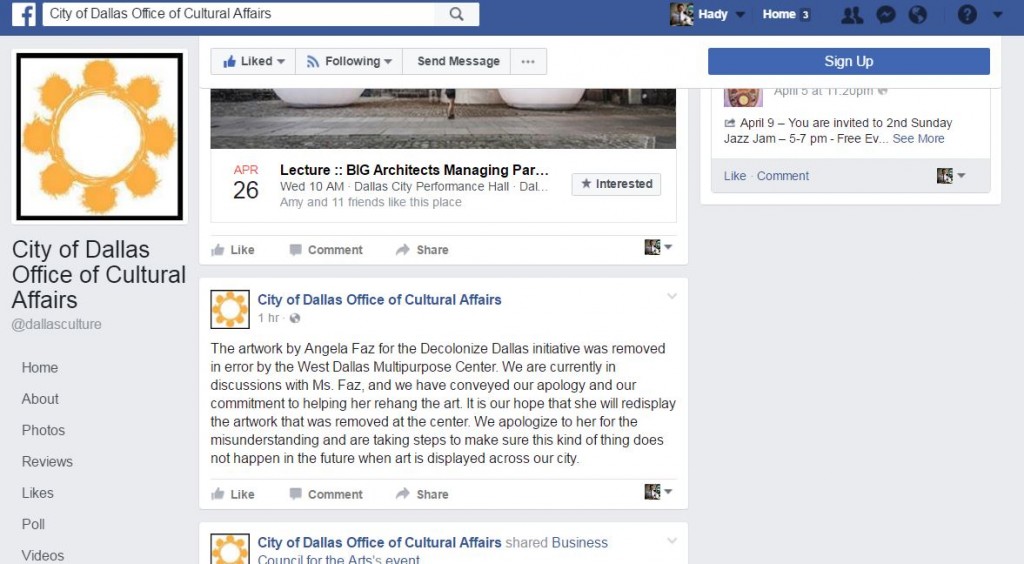

On Thursday, the Office of Cultural Affairs issued an apology via social media, Scripps personally reached out to Faz and she hopes the full work can be rehung.

“We don’t want to be part of censoring,” says Scripps. “No one believes that the voices that are part of Decolonize Dallas and the work deserves to be seen in neighborhood more than I do.”

The many players in this drama are still talking about how to resolve it.

Angela Faz, the artists, and the organizers of Decolonize Dallas hope all this sparks more dialogue about what’s happening in West Dallas – and arts equity.