Six insights On Van Cliburn, Legendary Pianist And Namesake Of The Van Cliburn Competition

ArtandSeek.net June 2, 2017 57In 1958, Van Cliburn took the Texas heat to the Soviet Union and made the Cold War a little warmer when he won the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. Today his legacy continues as the 15th annual Cliburn Competition, one of the world’s most prestigious piano competitions. The semifinals continue through this weekend.

In honor of the competition, Stuart Isacoff, author of “When the World Stopped to Listen: Van Cliburn’s Cold War Triumph, and Its Aftermath” joined Think’s Krys Boyd to discuss the life of the sweet small-town Texan turned American hero and piano icon.

Here are six insights about Cliburn from their conversation:

On how Cliburn’s gift was apparent at the age of 3-years-old:

“The very first clue was probably the one that he gave his mother. She was a small-town piano teacher in Kilgore, Texas with many young students and one day, one of her students had finished the lesson and she assumed had gone on home. And then she heard one of the pieces the student had been playing sounding on the piano in the living room. She called out to him that his parents would probably worry if he didn’t get home. Turned out, it wasn’t the student at all, but it was Van, who simply on the basis of hearing the music sat down and began to play it and he was 3-years-old at the time.”

On the special technique his mother had him do before he played a piano:

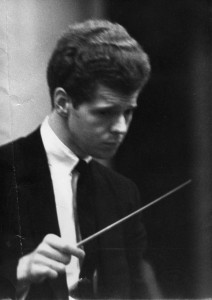

Van Cliburn conducting.

Photo: The Cliburn

“She had Van do things that most of the teachers at the time probably didn’t think about much. For example, she had him sing the music before he played it. And that gave him a certain insight into how to things come alive because, if you’re simply moving your fingers on a keyboard, you miss some of the clues that you would get from the visceral experience of actually singing- that is, where to breathe, how to phrase things, when something should be louder or softer. She gave that gift to him and he ran with it. He had begun this very unique approach to playing.”

On his obligation to serve:

“From the age of four or so, they actually had him serve them dinner and do the same for neighbors. So he would develop this idea that he wasn’t special, he wasn’t too special. And that his life should be a life for serving, a life of graciousness. Unfortunately, this had a negative effect in the concert hall because he began to worry so much about serving the audience, as if they were these guest that he had to wait on that it became a distraction for him. On the one hand, he had this job to do, of bring the music to life. On the other, he had to worry about whether he was really reaching the audience. That created a kind of divided self that gave rise to tremendous performance anxiety. So, from the age of four when he gave his debut, he reported that he had tremendous anxiety every time he had to preform.

Van Cliburn receiving flowers from the audience during the Tchaikovsky Competition (Moscow, April 1958). Photo: The Cliburn

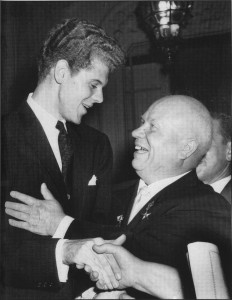

On Soviet political leader Nikita Krushchev’s historic decision to make Cliburn the winner:

Nikita Khrushchev embracing Van Cliburn, after Van won the Tchaikovsky Competition. Photo: The Cliburn

“Jury members actually approached Kruschev to say, I know this is highly unusual but we actual want to give this award to an American. . . What happened was Kruschev gathered his advisors and there were people on both sides of the issue. There were nationalists who felt the medal had to go to a Soviet. I mean, why would you create a Soviet competition and give it to an American? It seemed absurd. And then there were others who felt that the competition would never be taken seriously, if it was skewed politically. And Kruschev listened to both sides. And he came down to the side of giving it to Van… So, without Kruschev it couldn’t have happened. Gilels (widely regarded soviet pianist) had said to Kruschev, ‘If you give the award to Cliburn, it may end the Cold War.’ “

On finding Tommy Smith, the love of his life:

“He [Van] was closeted for most of his life. People who knew him well knew about the homosexuality but it was not something he could show easily. Especially not in Moscow, because it was such a crime there. . . Back home, it probably wasn’t much better. When president Johnson asked J. Edgar Hoover if it was OK to invite Van to the White House, Hoover said ‘Well, he is homosexual…’ and Johnson said ‘Well, I think most musicians are.’ So it was OK with Johnson, but it still was a difficult situation. When Van met Tommy, it was at a time in his life when he had really matured, he had most of his career behind him and they fell in love with each other. Suddenly, when Van was receiving awards, whether it was at the Kennedy Center or even a great award from Putin for service to the Russians- Tommy was with him. They traveled together. It was a deep and abiding love. And when Van got ill with bone cancer, Tommy really took care of him, watched over him, helped him as best as he could till the very last day. So I think that Van found a level of peace and solace in the last 20 years of his life with Tommy that maybe had eluded him before.

On why some thought that Van may have not cared about piano very much:

“She [friend Mary Lou Falcone] thought that for Van, the Piano wasn’t that important. I know it sounds shocking but I tend to agree with that. I think that the piano was a way for him to touch people, to reach people. And it wasn’t the instrument itself that was so important. In a way, he lived for those moments. Not for the moments of being on stage and performing, we know he became a nervous wreck whenever he had to do it. For the moments of reaching out and touching people and having them reach back. I think that’s really what drove the man.

Van Cliburn with President and Mrs. Lyndon Baines Johnson and Vice-President Humphrey and Mrs. Humphrey on his right, April 10, 1968.

Photo: The Cliburn

Interview responses have been edited for length and clarity.