Sex And Power And Toying With People’s Lives

ArtandSeek.net July 5, 2018 49Use someone for sex because you can and then, with impunity, toss him or her away like an empty Veuve Clicquot bottle. It’s been said before, but let’s chime in: Christopher Hampton’s sophisticated stage adaptation of ‘Les Liaisons Dangereuses’ – currently on stage in a crisp revival at Theatre Three – couldn’t be a more apt drama for our #MeToo and Time’s Up moment.

Yes, one does hope this is more than a ‘moment,’ that some long-lasting changes might be made to the power imbalance between the sexes. But the persistent relevance of ‘Les Liaisons’ should give one pause.

When Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ original novel appeared in 1782, it was an explosive tell-all about the Parisian aristocracy romping and wrecking lives for sport. It also offered an indictment of the libertinism the French Enlightenment had degenerated into: Educated freethinking now included tricking women into bed and bragging about it. By 1985, when Hampton’s theatrical version premiered, first in London then on Broadway two years later, the play was hailed for its satiric take on the purported selfishness and upper-class indulgence of the ’80s, the Age of Thatcher and Reagan.

Now it’s Harvey Weinstein’s turn in the pillory. ‘Les Liaisons’ is impossible to watch today without thinking of Weinstein, Bill O’Reilly, Charlie Rose and the other powerful males accused of sexual misconduct, using their positions to coerce victims into silence. Funny, how such a smart stage drama just keeps dragging in the latest definitions of class privilege, masculinity and vulnerability. Can a drama of salons and servants really feel so relevant? Consider what transpired at the Dallas Theater Center with former casting director Lee Trull being fired for ‘inappropriate behavior’ – which set off a still-simmering controversy over how it was handled and reported on. Now imagine if ‘Les Liaisons’ just happened to be scheduled on the DTC season. A righteous and bitter explosion might have gone off in the local theater community.

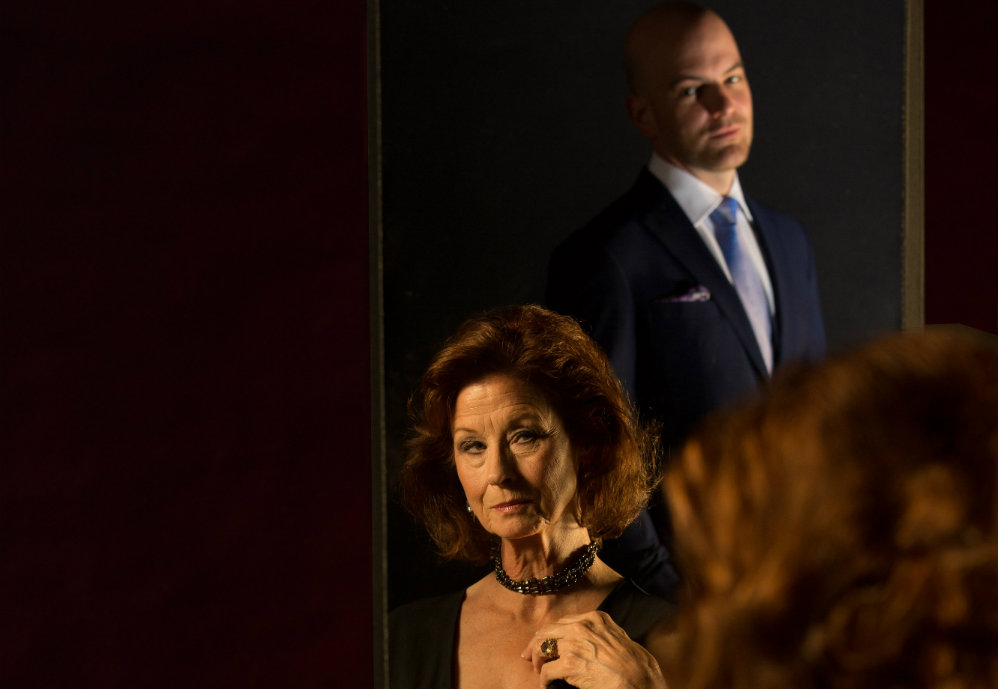

Cindee Mayfield as the Marquise de Merteuil and Brandon Potter as the Vicomte de Valmont. Photo: Jeffrey Schmidt

The generally well-executed Theatre Three staging, directed by Tiffany Nichole Green, is not the first to be done in modern dress. The National Theatre presented its own revival two years ago with Dominic West (‘The Wire,’ ‘The Affair’). The man at the center of the play would seem to be just another Don Juan. But the Vicomte de Valmont sets out to bed a famously religious, married woman just to prove he can. He’s confident he’s that charming, that disarmingly devious. Valmont’s not racking up high scores; for him, it’s the emotional challenge Madame de Tourvel presents that’ll burnish his reputation as a rake. It’ll give him that extra pleasure, humiliating this straitlaced woman who’ll enjoy herself erotically while tormenting herself morally.

There lies the difference between Valmont and Weinstein et al. Bill Cosby was convicted on three counts of drugging and then sexually assaulting women. Matt Lauer allegedly had his office turned into a medieval trap. Valmont certainly gets angry and ugly with the Marquise de Mertuiel, his former lover and now his rival in toying with people’s lives. But it’s difficult to see him actually resorting to blunt force or getting a victim blind drunk.

Valmont enjoys the game too much, especially with a good opponent. Played by Brandon Potter at Theatre Three, Valmont’s a seducer, although what he does with the innocent Cecil de Volanges (Samantha Behan) – another one of his targets along the way – would, by today’s standards, constitute statutory rape. It doesn’t matter that she enjoys herself with him. She’s still underage. And even if she were fully mature, his seduction of her would be callous. He’s just doing it to help La Marquise revenge herself on Volanges’ fiance, a previous lover who’d spurned La Marquise.

The National Theatre 2016 revival of ‘Les Liaisons Dangereuses’ starred Elaine Cassidy, Dominic West and Janet McTeer. Photo: National Theatre

There’s no doubt in ‘Les Liaisons’ that Valmont is a bad man, a cynical sexual predator. But being attractively smart, rich, amusing or stylish – these do complicate the picture. It’s not that charm redeems the criminal; the point is it increases his dramatic appeal. John Milton made Lucifer the most arresting figure in ‘Paradise Lost’ for a reason.

And what of La Marquise, who presents a complicating case of female equality, even superiority, when it comes to using and abusing people sexually? At the heart of ‘Les Liaisons’ is her speech defending her need to be even more devious, more ruthless, than the men she encounters – out of self-preservation. She’s an independent, attractive widow in a world where dynastic marriages with powerful men are the major engines of wealth and property. She has her aristocratic title, of course, but otherwise, she must follow her ironclad rules, using her brains, caution and charm.

Charm, unfortunately, is something Potter doesn’t really convey as Valmont. What made the late Alan Rickman, who originated the role on stage, and John Malkovich, who starred in the 1988 film version, delightful was their feline narcissism. That playful self-awareness is key to Valmont’s appeal because through much of the first act, he’s play acting: He makes a show of being the attentive nephew, the altruistic nobleman, the doting lover, all to seduce de Tourvel – even as he mocks these gestures, all this tiresome do-gooding. Both Rickman and Malkovich let us see the ‘actor’ commenting on the acting, they let us enjoy the sardonic performance, the eye rolls and sighs. Potter’s delivery is flat and dry, his ironies often come across as muttered exasperation.

It’s when Le Vicomte hits hard times and his relationship with de Tourvel (Lydia Mackay) turns out not as he hoped that Potter becomes convincing. Direct expressions of emotion – hurt, anger, doubt – activate him, they suit him better, it seems, more than droll self-reflection. He has a habit of pivoting as if his head, neck and shoulders were a single unit, his arms and the rest of his body dangling from them like a marionette’s. He does this to confront someone foursquare, feet planted, chin up. That and his rock-crusher voice make him formidable, if not subtle. He doesn’t project weakness well, for instance, the broken spirit Valmont exposes in his final confession.

John Malkovich as Valmont in the 1988 film, ‘Dangerous Liaisons.’ Photo: imgur.com

The performer who truly enjoys all the games, all the delicate ironies that twist like scrollwork throughout ‘Les Liaisons’ is Cindee Mayfield‘s La Marquise. This is Mayfield’s richest role in years and she relishes all of it, delivering La Marquise’s catty put-downs as well as her savage, calculated wisdom on triumphing in this man’s world. If anything, Mayfield starts out too imperious already. La Marquise needs to show us some smoulder, some warmth (more than Mayfield does, at any rate). It’s her only weakness, this residual affection and admiration between her and Valmont, and sensing that amplifies our awareness of all that they end up losing here when they go to war, the real heartbreak that motivates these battle-scarred bedroom veterans.

But that’s a small reservation; otherwise, this is Mayfield’s show, and she knows it.

Speaking of scrollwork, director Green does add a few unnecessary frills – like the white animal masks the actors don and doff during scene changes. It’s as if Green couldn’t just tell this brilliantly constructed play in a straightforward fashion. She felt a director’s job was to add stuff, like metaphors – Valmont’s a goat, La Marquise is a fox – stuff that tell us nothing we don’t already know.

Brandon Potter, Lydia Mackay and Cindee Mayfield at Theatre Three. Photo: Jeffrey Schmidt

Other than that, Green’s production is admirably quick, forceful and clear, benefiting immensely from Inseung Park’s superlative set with its two-story, white spiral staircase on one end, like a giant spider’s web. The entire design is clear, sleek and open yet twistingly elaborate at the same time. Nice – there’s your metaphor.

Hampton’s adaptation of de Laclos’ novel is brilliant because it simplifies so much. ‘Les Liaisons’ is an epistolary novel, after all, with a great deal of correspondence (including secret letters) spread throughout a network of aristocratic friends, spies and servants. Yet Hampton cleverly keeps letters and letter-writing a major agent onstage.

He also retains the essence of de Laclos’ view of this jaded world of salons and ruined reputations. For those who, in our #MeToo moment, find the idea repellant that sexual predators are portrayed with a smidgen of sympathy or style, there’s this to consider: Christopher Hampton has insisted that a moral universe truly operates in ‘Les Liaisons.’ In a 1988 interview I did with him, he pointed to the endings for Le Vicomte and La Marquise as perfect proof. Justice prevails.