State Of The Arts: Artist Isa Genzken And The Nasher Sculpture Prize

ArtandSeek.net April 4, 2019 103

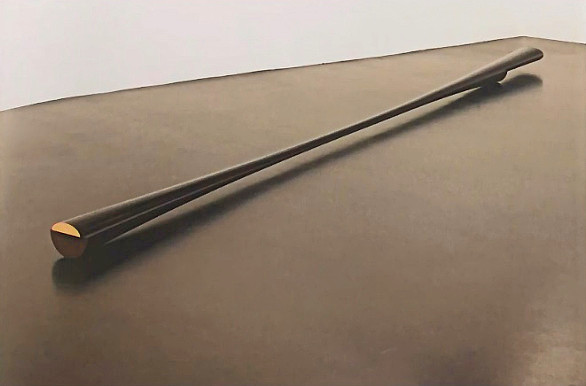

Isa Genzken, “Black Hyperbolo ‘Little Nuts’” (Schwarzes Hyperbolo ‘Nüsschen’), 1980, lacquer on wood. Image courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

This weekend, the Nasher Sculpture Prize will be officially presented to German artist Isa Genzken. She’s had a four-decades-long career, creating everything from elegantly simple sculptures to miniature skyscrapers made of discarded plastic to disturbing, sprawling installations. Genzken won’t be attending Saturday’s gala, but Art & Seek’s Jerome Weeks says this isn’t unusual for the enigmatic artist.

In contemporary European art, Isa Genzken’s a pioneer, a legendary figure. In America – not so much. The Dallas Museum of Art may be the only major Texas museum with a sculpture of hers in its collection. It’s one of Genzken’s series of ‘doors’ from the late ‘80s. Actually, the artwork resembles a low, crude, concrete wall on a steel pedestal. It’s blunt and simple – like a chunk of abstract minimalism left outside to fall apart.

But – not quite.

Door (Tür), concrete and steel, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Rachofsky Collection and purchase through the TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund © Isa Genzken

“This is an artist whose works might look abstract when you first look at them,” says Laura Hoptman. “But they are all narrative, every one of them – particularly the works that began in 1987. Those cement works depict post-war Berlin or are inspired by the ruins of post-war Berlin.”

Hoptman is executive director of the Drawing Center in New York. In 2014, she was one of the curators of Genzken’s first major retrospective in the U.S. The show ran in New York, Chicago and at the DMA. Hoptman argues that the backstory with ‘Door ‘– its references to architecture and the spectacle and decay of urban life – all of these recur in Genzken’s art.

“If you look at the work as a ruin,” she says, “you can see this through-line from 1987 to 2003 with her great group of assemblages called ‘Empire/Vampire Who Kills Death,’ which was inspired by the tragedy of 9/11 – which unfortunately, Genzken herself witnessed.”

Berlin and New York have been Genzken’s homes at different times. She grew up in one after it had been bombed flat. She lived in the other when the Twin Towers were destroyed. Needless to say, her deeply disquieting, sometimes even chaotic-seeming works reflect these events. What’s also reflected: her love of both cities, even as she has decried the transformation of old Berlin into yet more international, glass-boxed corporate towers and luxury high-rises.

While in Manhattan, Genzken created three collage books chronicling her life there. They were assembled together as ‘I Love New York City, Crazy City’ (1995-’96). They contain diary entries, takeout menus, calendars, performance programs, selfie photos, all of them tracing Genzken’s wandering, club-hopping life there, staying in everything from high-end hotels and youth hostels to, yes, a hospital.

Isa Genzken’s ‘Rose’ in Zucotti Park in New York City – the location of the Occupy Wall Street protests.

On a more colossal urban scale, both cities have perhaps Genzken’s most popular, public works: painted-steel roses, 26-feet-tall. Hoptman calls them Genzken’s bouquets but also notes they have more than romantic connotations: The rose is the traditional symbol of German democratic socialism. And one of the two roses in New York is in Zucotti Park, the site of the Occupy Wall Street protests.

Genzken may return to certain, central ideas about alienation, commodification and urban space, but Hoptman grants she can still be hard to peg as an artist, which contributes to her relative obscurity outside of Europe. She’s been boldly creative in so many different directions. Hoptman compares her to Zelig, the Woody Allen character who kept changing and popping up in different eras.

“She first appears in the late 1980s, and her work was interpreted through the lens of minimalism and post-minimalism, though that was somewhat misguided,” Hoptman says. “Then she re-emerges in the mid-1990s as somebody who made assemblages, which is a very different thing than creating a sculpture from whole cloth. She’s also been enormously active in film and performance, painting and drawing.”

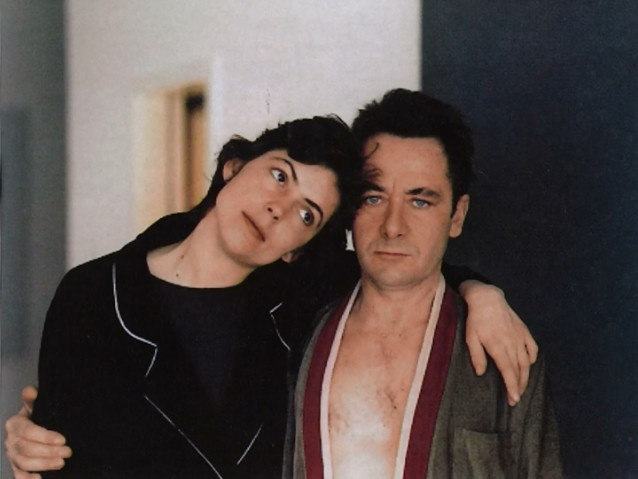

Isa Genzken and Gerhard Richter.

Even at her simplest, Genzken has been innovative. Her earliest, most beguiling sculptures are long wooden poles with gentle curves – called ‘elipsoids’ or ‘hyperbolos’ (top). The curves allow the pole, when lying on the floor, to seem as if it’s floating above it. Those curves are derived from audio waves, and in the late ‘70s, they could not have been carved by hand – not without help.

“As a student,” Hoptman says, “she found a computer programmer who helped her make 3D models of sound. It is very possible that she was among the very first artists to work in this way with a computer.”

Much later, Genzken used store mannequins in her provocative, ragged-looking assemblages, littered with cheap or discarded items. It’s these assemblages – table-top-sized or whole-room installations – that are her trademark work these days. But it’s revealing that Genzken doesn’t call the mannequins either mannequins or ‘statues.’ For her, they’re ‘schauspieler‘ – ‘actors’ – meaning her installations are akin to stage dramas or a movie scenes. Again, she’s telling a story (even in the relatively small ‘Empire/Vampire’ below, note the presence of toy action figures).

But Hoptman says another reason Genzken has not had a typical rise toward international renown is simple. Sexism.

“Genzken was married to Gerhard Richter, arguably at the time of her marriage the most famous German artist,” Hoptman says, “and that, of course, took a toll on her reputation.”

One of Genzken’s series of assemblages called ‘Empire/Vampire.’ This one is ‘Empire/Vampire III, 16,’ 2004. Mixed media, metal, glass, plastic, lacquer, wood. Image courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

Richter was initially Genzken’s teacher. So some attributed Genzken’s early success to his influence. But both belong to the post-war German generation; there was bound to be some overlap in their thinking. Both, for instance, have defiantly confronted their country’s Nazi past – even when that included their own families. Genzken’s grandfather was a Nazi doctor. Richter painted a famous portrait of his ‘Uncle Rudi’ – in full Wehrmacht uniform and coat.

After ten years, Genzken and Richter divorced bitterly. Since then, Genzken has spoken publicly about her treatment for bipolar disorder and alcoholism. Her life has had its troubles – and its chaos.

But Hoptman argues that it’s a cheap form of biographical criticism to attribute the aggressively disjointed and oddly lonely-seeming nature of Genzken’s contemporary work to her recent mental issues. After all, Genzken was evoking Berlin’s blasted, crumbling walls and turning cinder blocks into silent, uncommunicative ‘transistor radios’ as long ago as the 1980s.

In fact, Hoptman argues that a final reason Genzken is not as well known as she should be is “she’s a woman artist struggling to make her name, and she was difficult to work with. And that really is a very large element especially in the commercial art world.”

Isa Genzken, OIL XV / OIL XVI, 2007 Installation wall piece: 23 panels in three segments: aluminum, metal foil, adhesive tape, metal, printed paper Floor piece: six parts: two mannequins, two plastic cases, one glass bowl, metal foil, plastic, fabric Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz © Isa Genzken

Temperamental male artists get excused as geniuses. Difficult female artists can lose careers. And Genzken has certainly been unpredictable and … ‘difficult.’ She once had a friend artist interview her for a short videotape – titled ‘Why I Don’t Do Interviews.” During a ‘New York Times’ interview in 2014, she left in mid-interview. She wasn’t angry – she had just wandered off to look through the Museum of Modern Art’s galleries. And that same year, when that major retrospective came to the DMA, it was announced Genzken would be at the opening. Then it was announced she wouldn’t be.

Then, to the surprise of the DMA officials themselves, Genzken just … showed up.

Because of the artist’s current poor health, that’s not likely to happen at the Nasher gala. But it’s just like Genzken that even her public appearances carry stories with them.

Image outfront of floating astronauts: Isa Genzken, Oil XI, 2007. Vinyl, plastic, and aluminum suitcases; silk screen on laminated fabric; jackets; stuffed animals; plastic; paper; frames; and three fabric-and-plastic space suits; 20 parts: overall dimensions variable. Installation view at the German Pavilion, 52nd Venice Biennial, Venice, Jun 10–Nov 21, 2007. © Isa Genzken courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. Photo: Jan Bitter, Berlin.