Altars, Traditional And Contemporary, Remember Victims Of Immigration And Gun Violence

ArtandSeek.net November 26, 2019 52Yellow caution signs with the image of a father, mother and daughter running were once posted along Interstate 5 in Southern California. The signs were a source of controversy – some said they were offensive and dehumanized immigrants.

Mexico City artist Betsabeé Romero tweaked that image in her latest exhibit, “An Altar in Their Memory / Un Altar en Su Memoria,” recently on display at the Latino Arts Project, a new museum in the Dallas Design District.

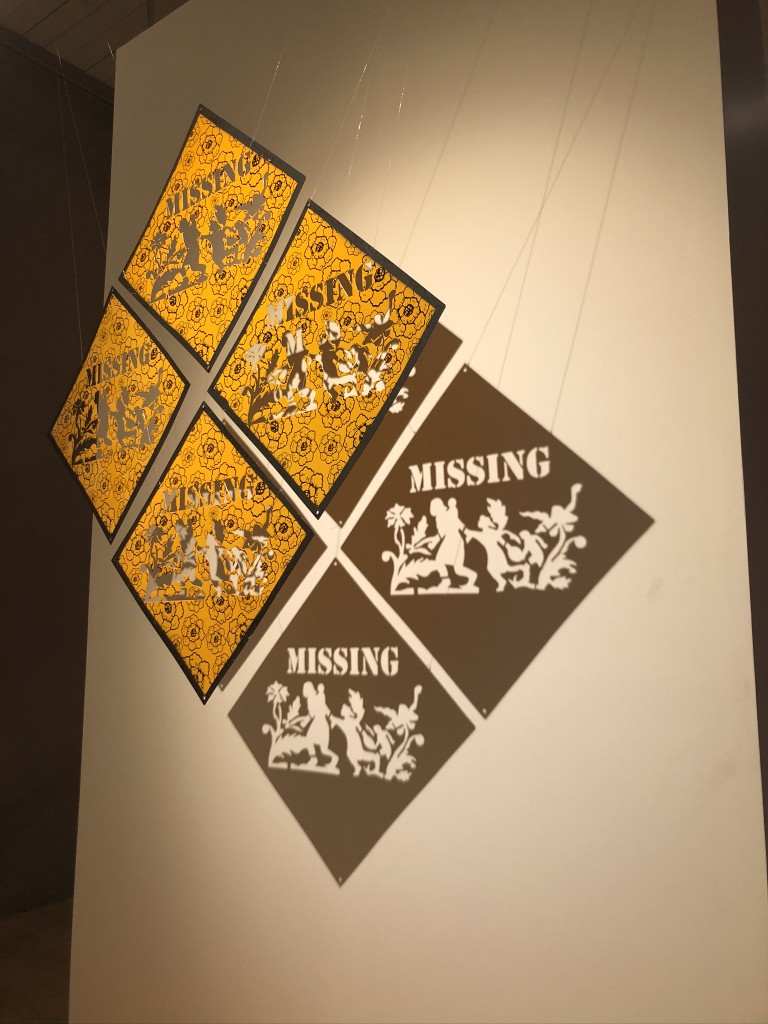

In this exhibit, which highlighted the issues of immigration and gun violence, the word MISSING – instead of CAUTION – are stenciled on diagonal-shaped signs. The image is of a mother with three children.

Betsabeé Romero tweaks the “Caution” sign often found near the US Mexican border in her exhibit, “An Altar in Their Memory / Un Altar en Su Memoria.” Photo: Stella Chavez

“What Betsabeé, the artist, wanted to do, basically, is to pay a tribute to those missing and mothers that [are] trying to bring their children to a better life and they passed away,” said Carlos Gonzalez-Jaime, the museum’s executive director.

He recently gave students from W.W. Samuell High School a tour of the exhibit. The museum waives the entrance fee for school groups from the Dallas Independent School District. On this day, the young visitors are from an Advanced Placement Art class.

“It’s great because of how [the artist] works through a topic and that’s what the AP students are doing,” said Charles Petty, a visual arts teacher and chair of the Fine Arts Department at Samuell. “They pick a subject or topic and they investigate and they make different pieces of art that are all around the same series over the course of the year.”

He said Romero’s work challenges and resonates with his students. One example: a row of orange, yellow and pink shooting targets hanging from the ceiling. They’re made of intricately-cut tissue paper. Skulls surround the silhouette of a figure riddle with what looks like bullet holes. The work honors those killed by gun violence.

From the exhibit, “An Altar in Their Memory / Un Altar en Su Memoria,” by artist Betsabeé Romero. Photo: Stella Chavez

Demi Joi Dacal Dacal, a twelfth-grader at Samuell, said she could relate to it.

“Where I came from in Louisiana like, it’s a lot of dead going on,” said Demi Joi. “Like, where I was raised, it was always people dying, getting shot and some of my family members, too.”

Demi Joi says young people spend a lot of time on their phones, but that seeing and discussing art like this can help her and her peers better understand real-life issues.

Crystal Silva, also a senior at Samuell, said she felt emotional seeing the work because “a lot of people die and it represents that.”

But Crystal and her classmates were also struck by the colorful, enormous altar that greeted them as they entered the museum.

Detail of a large traditional altar in the exhibit, “An Altar in Their Memory / Un Altar en Su Memoria,” by artist Betsabeé Romero. Photo: Stella Chavez

Sugar skulls, bread known as pan de muerto, candles and marigold flowers made of tissue paper adorned the display. It’s just as you would find during Dia de Muertos or Day of the Dead, a celebration of life and death throughout Latin America.

“When you see how delicate and how special is the work of Betsabeé – it’s so profound, it’s so powerful. It’s a lot of meaning behind the work,” Gonzalez-Jaime said.

Take the piece that looks like a dreamcatcher, made from bright red children’s sweaters.

A Dreamcatcher made from children’s sweaters, from “An Altar in Their Memory / Un Altar en Su Memoria,” by artist Betsabeé Romero. Photo: Stella Chavez

Or the row of tires hanging from the ceiling, gold leaf images of a family on them. Look through the center of the tires and you’ll see the shadow of an immigrant family cast by a “MISSING” sign.

Tires from “An Altar in Their Memory / Un Altar en Su Memoria,” by artist Betsabeé Romero. Photo: Stella Chavez

Kristie Hunger, a visual arts teacher at Samuell, said it’s essential that teachers understand what some of her students and their families have experienced coming to the U.S.

“It’s affecting me deeply just to see the [gun violence statistics] on the wall,” Hunger said. “And the numbers of immigrants coming over that didn’t make it across the border into safety that were fleeing death, only to find death at the border.”