David Jeremiah Explores Police Brutality, Masculinity In New Exhibit

ArtandSeek.net February 11, 2020 40Lamborghini-red paint popping off the canvas, children’s play cubes with a Rice Krispie-like coating of concrete and shiny gold bullet casings that form a play on words, draw the attention of visitors at David Jeremiah’s new exhibit “Things Done Changed.”

David Jeremiah discusses his artwork with visitors to the gallery. / Photo: Elizabeth Myong

Hosted at the Public Trust gallery, the exhibit opened this month to a crowd of more than 300. While Jeremiah is quickly building a reputation in Dallas’ contemporary art scene, some still consider him an outsider — and he is. According to a new study, 85% of artists in museums are white.

Jeremiah first gained notoriety in Dallas with his exhibition “The Lookout.” He locked himself in a cell for three weeks and had visitors paint a white Ku Klux Klan hood onto his body. While some consider his art to be extreme, Jeremiah said he wants people to focus on having a candid conversation about race in Dallas.

“A lot of people were like, ‘bro, this is too close to home,’” he said. “Well you can look at it like that if you want to, or you can see it as it is so close to home that we almost have to have the realest version of this conversation, so that we’re not wasting anybody’s life on that day.”

Jeremiah tried to have an honest conversation in “Things Done Changed” with pieces that explore issues from police brutality to black masculinity.

The Story Behind The Art

Much of Jeremiah’s work is influenced by his childhood in Dallas — his perception of race relations and the police growing up in predominantly black neighborhoods, his boyhood appreciation for Lamborghinis and his favorite shows like the Japanese anime series Dragon Ball Z.

The Lamborghini has been a big source of inspiration for Jeremiah who uses the signature red and blue colors in his artwork.

He said the Lamborghini’s “beauty and essence” is rooted in ritualistic violence, explaining that the Italian manufacturer started naming their models after Miura fighting bulls in 1966.

“If there’s another beautiful, perfect body that’s rooted in ritualistic violence as well it’s the human body,” he said.

Dragon Ball Z, once just an anime show Jeremiah liked to watch, became a way for him to understand black masculinity during his time in prison. He said he was drawn towards the recurring plot of Vegeta, a prince who constantly seemed to be in battle with his nemesis Goku.

The character reminded him of the ways men in prison, including himself for a time, would act like Vegeta, calling themselves gods and kings as a way to “uplift theirselves in this mess of a country that’s against them.” He called it a “re-brainwashing” done by black men to survive in the world.

Characters from the show also change form when they are enraged. Jeremiah started to see this transformation as a metaphor for “black masculinity pushed too far.” He said he sees the man who killed the five Dallas police officers on July 7, 2016 as an example of this.

Jeremiah also juxtaposes challenging subjects like police brutality and racial violence with the innocence of toy-like pieces for his 5-month-old son. In Khild’s Play – Building Blocks, the wooden blocks represent Jeremiah’s son while the concrete encasing represents the prison he says his son was born into as a black boy in America. Jeremiah said the piece is also a reflection of his own life decisions that eventually led to his time in prison.

Khild’s Play-Building Blocks on the Public Trust gallery floor. / Photo: Elizabeth Myong

“He’s already imprisoned and if he plays around too much, he can put himself in an even more defined one than the one he’s already born into,” Jeremiah said.

Reflecting on the series, Jeremiah said while his son is too young to understand the concepts in Khild’s Play, it’s an effort to prepare for his future.

“I catch myself trying to give him energy that he’s not ready for, that comes from a worried place,” he said. “You got to be a man.”

What It Means To Be “Primitive”

Jeremiah was once called a “primitive” artist by an acquaintance in the Dallas art scene who commented on his lack of formal art school training. While offended at first, Jeremiah channeled his frustration into his work, embracing a “primitive” way to make art through the sledgehammering, ripping, punching and kicking of wood. What emerged was The Blacks, The Gods and the Devils, a collection of pieces that satirize the very idea of what it means to be “primitive.”

The Story. The Blacks, The Gods and The Devils. / Photo: Elizabeth Myong.

Scattered across the back wall of the gallery, the rugged surfaces and jagged edges look like game pieces in Jeremiah’s mythological world. He calls this universe “The Story.” It is inhabited by creatures he created, like The Blacks, who are the first men and The Gods, who are golden symbols of religion.

“Why not make fun of the primitive art of anything — what did the first person do?” he said. “You start from somewhere and the start is always primitive to a degree.”

Jeremiah’s work often involves going against the grain. Visitors can find a “F**k You” scrawled on the edge of his canvases. It is his own little inside joke, poking fun at the traditional idea that artists should completely paint the sides of the canvas.

A “Redemptive Afterlife”

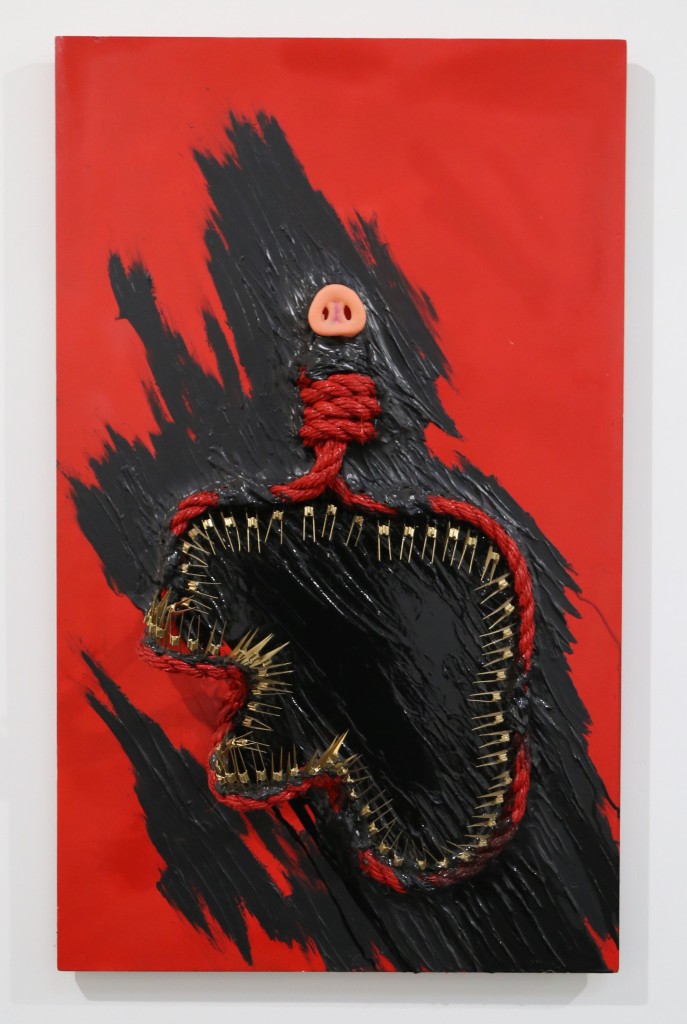

For the series Hamborghini Rally: Soul Hunt City, Jeremiah has an eclectic set of inspirations from Lamborghinis to the movie Hellraiser, to video games like Gran Torismo and Mario Kart.

Each of the pieces represent one of the police officers who was killed during the Dallas police shooting three years ago. They depict redemptive afterlives, according to Jeremiah.

“All of them are in hell but their hell is depicting my favorite video games growing up,” he said. “So basically, they are trapped in this video game where like you perpetually have to chase down this white ghost to get their souls back.”

The Story. Hamborghini Rally: Soul Hunt City is a vivid red color. / Photo: Elizabeth Myong

Imagery of pigs and Lamborghinis combine on the vibrant red coated canvas, which has a life-like rubber snout protruding from the center. Jeremiah said in the world of his series, the longer you stay in this version of hell, the more distant you become from who you were while living.

“So just imagine that they looked like they did when they were still in their flesh and blood body, but over the duration of these past three and a half years going on four years, they’ve turned into this bastardization, hybridization of pigs and Lamborghinis,” he said.

Jeremiah also created a gold grill, decorative covers for teeth, made out of a spool of prison razor wire for two of the “Hamborghini” figures.

“I wanted to give each of them a different rendition of a gold grill to anchor them in a physical element of the stigma that I feel like cops attribute to their prey,” he said. “You know that ni**a has a gold grill, he a thug.”

A visitor looks at one of the Hamborghini Rally pieces. / Photo: Elizabeth Myong.

Jeremiah said he does not intend to promote violence against police with his work. Instead, he wants to find new ways to promote peaceful conversations — something black people continue to do through marches, protests and other nonviolent forms of resistance.

Jeremiah calls the black, sticky looking substance on the canvases “the material.” He won’t share what material or technique he uses to make it.

“That’s all the black sh*t inside of me I’m getting out conceptually, but I don’t talk about what it is,” he said. “There’s some things you got to keep private.”

Jeremiah said art is like therapy for him, but he also hopes that it provokes honest conversation in his hometown where 5 police officers were killed on July 7, 2016.

“Dallas is not going to get away from me,” he said. “I feel like what better place to have a realer version of a real conversation.”