Lost Texas Music Pioneers

ArtandSeek.net August 20, 2020 33In his new book, long-time music writer Michael Corcoran profiles influential Texas musicians of the past — some of the artists and producers who’ve mostly been forgotten. They once were significant creators of country music, gospel, rock, blues and hip-hop. KERA’s Jerome Weeks talked with Corcoran about the lost Texas music pioneers he calls “ghost notes.”

Michael, the title of your new book, Ghost Notes: Pioneering Spirits of Texas Music (TCU Press). What are “ghost notes”?

‘Ghosts notes’ is an audio term. It’s a little sound in the recording that you just barely hear it. It’s like the tapping on the drums of the index finger while you’re hitting the drums. Or guitar players – they’ll sometime mute a string and get a muted sound. And it’s a sound in the background, but it’s the sound that really drives the beat.

Amos Milburn at the piano, right. Photo: YouTube

So ‘ghost notes’ refers to the more than two dozen Texas musicians and producers in your book. They’re pioneers. They created new music styles — in gospel, R&B, country, hip-hop. But they eventually were overshadowed by more famous artists. They never got the fame they deserved. Some of them people may know – like Roky Erikson or former Dallas rapper The D.O.C. — but I’d like to focus on two I admit I knew only a little about.

What drew you to Amos Milburn and Charles Brown, two black piano players from the ‘40s and ‘50s?

Well, first of all, I became a huge fan of Amos Milburn. I was reading Fats Domino’s book, and he mentioned that his primary influence was a guy named Amos Milburn from Houston. And I just thought, well, if this guy influenced Fats Domino, why isn’t he better known?

Amos Milburn was blistering through piano tunes like “Down the Road Apiece” in 1946 – years before Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis. So you see Amos Milburn as an important Texas bridge between boogie woogie piano, jump blues and rock ‘n’ roll.

Yeah, dance music is one of the things that’s distinguished Texas music. It’s why Texas musicians were some of the first to use electric guitars — like T-Bone Walker. They had to fill those big dance halls.

Charles Brown. Photo: YouTube

And then, as I was doing research on Amos Milburn, this name Charles Brown kept coming up. And so, I thought, well, that’s really interesting because Charles Brown is a primary influence on Ray Charles. He’s got that mournful voice. It’s very sensual in a brooding way. And that’s what Ray Charles picked up and changed his sound when “Drifting Blues” came out in 1946.

And in your research, Milburn and Brown, who was also from Texas, they often crossed paths.

Well, they were roommates, and they stayed in the same hotel room together. And I read Amos Milburn’s bandmembers said that he was gay. And Charles Brown’s wife said that Charles was gay.

So I thought that was really interesting. Here’s these two influential Texas musicians, and nobody really knows about them. And on top of that they were gay. [One sign of their relative lack of fame: Although jump blues fans have kept Milburn’s name alive online, you can find albums and record labels that still spell his name three different ways: Milborn, Milburn, Milburne. And while millions may know “One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer” from such recording greats as John Lee Hooker, it was Amos Milburn who first recorded it. For his part, Charles Brown finally achieved some renewed acclaim in the ’80s, thanks in part to Alligator Records, guitarist Danny Caron and Bonnie Raitt, who had Brown open for her on tour.]

So I called Charles Brown’s manager, this guy named Howell Begle – a great guy, he started the Rhythm and Blues Foundation to help black artists recoup royalties.

And I didn’t even mention it to him, but he says, “You know, Charles and Amos used to live together. They were a couple.”

So right off the bat, I got confirmation. But back when they were a couple, you could be thrown into jail for being gay. You had a choice between the closet or the cell block. And in the mid-‘50s, their careers dropped off significantly.

Now, I’m not sure if it was because they were gay. One of Charles Brown’s band leaders said that Charles had an incredibly bad gambling problem. You give him a thousand dollars and it’d be gone in ten minutes. He thinks that had more to do with them not having gigs.

But I don’t know – these two guys are just so talented.

I chose them as examples of the research you do in Ghost Notes. It’s a collection of magazine and newspaper features you’ve written, plus liner notes and updated research. It’s an extension of your earlier book, All Over The Map. That explored the incredible range of Texas music.

Michael Corcoran. Photo: Todd V. Wolfson

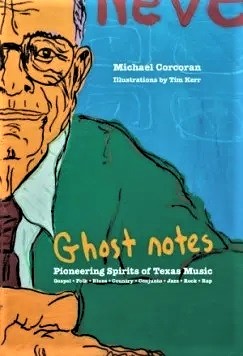

But Ghost Notes looks completely different. It doesn’t look like a typical music history. If it weren’t for the size of it and your name on it, I actually might have taken it for a children’s book. Instead of the usual, black-and-white, historical photos, it has big, brightly colored, hand-painted illustrations. Why?

Finding pictures, getting clearance for pictures, that sort of thing — it’s a huge pain in the butt. I’d love to hire just one person to handle the illustrations. And also, I didn’t want it to look like a sequel to All Over The Map. So I chose an artist to do illustrations for the whole book — a guy named Tim Kerr, who’s in Austin. He’s sort of a legendary musicians from his time in the Big Boys. And he started doing these really cool portraits around town.

So I asked him if he wanted to do it, and he’s a bit of a music history buff, so he said, ‘Sure.’ And I think his paintings really make this book stand out as a rare combination of art book and a music history book.

It’s a nice, sturdy book.

Weighs about two and a half pounds.

Michael Corcoran’s customized Spotify playlist – inspired by the musicians researched and profiled in Ghost Notes. The songs include: “The Grand Finale” by former Dallas rapper The D.O.C., “A Mother’s Last Word to Her Daughter” by Washington Philips, “Two-Headed Dog” by Roky Erickson, “God Moves on the Water” by Blind Willie Johnson and “Up the Country Blues” by Little Brother Montgomery.

Got a tip? Email Jerome Weeks at jweeks@kera.org. You can follow him on Twitter @dazeandweex.

Art&Seek is made possible through the generosity of our members. If you find this reporting valuable, consider making a tax-deductible gift today. Thank you.