Julius Eastman, A Misunderstood Composer, Returns To The Light

ArtandSeek.net June 22, 2021 52When composer Julius Eastman died in a Buffalo, New York hospital in 1990 he was 49 years old, alone, and his music was scattered to the winds. Only recently, friends and scholars have been slowly sheading light on Eastman’s music and the details of his final erratic years. A new recording of his hour-long work, Femenine has just been just been released and NPR reviewer, Tom Huizenga has been listening.

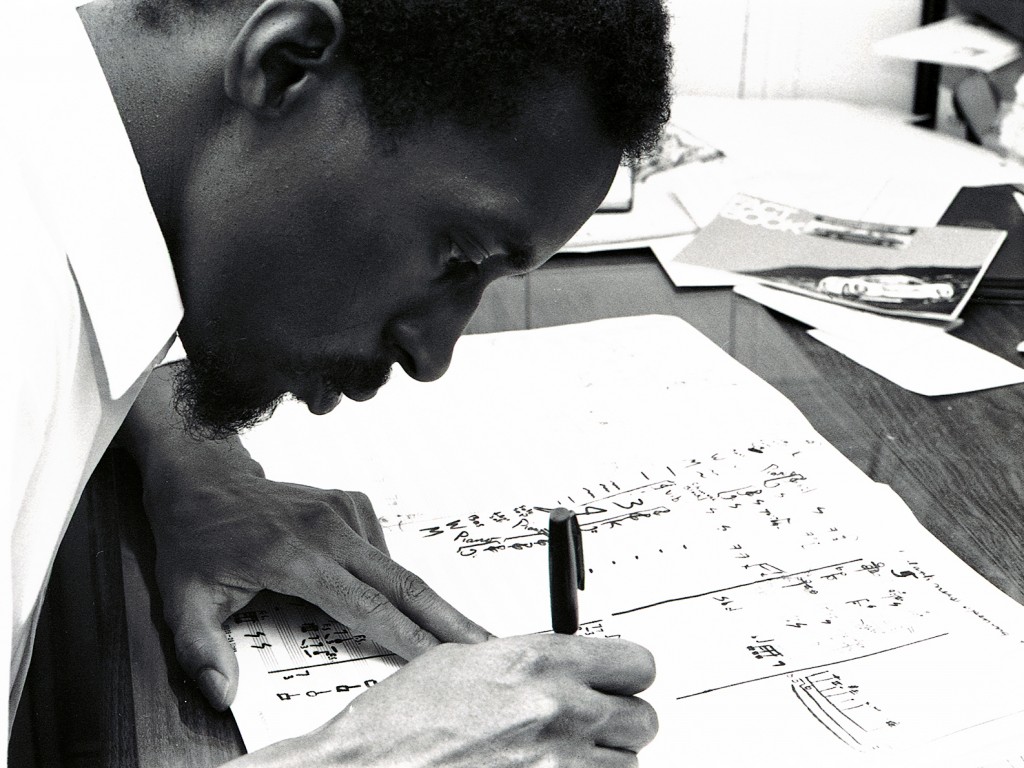

Composer Julius Eastman’s music is slowly moving from neglected to championed. Photo: Donald Burkhardt

Editor’s note: This story includes multiple uses of offensive language.

There have been many misfits in classical music, but Julius Eastman stands tall among them.

In a combustible career, the late composer swerved from critical acclaim to gate-crashing controversy, and from success to homelessness. To be proudly gay as a composer in the 1970s was brave enough; to be Black and gay in that world, even more so. But that confident self-awareness enabled Eastman to write music that was challenging, mischievously irreverent and sometimes ecstatic. Today he’s a visionary to many, even if his insistence on incorporating racial slurs into his titles still ruffles feathers.

Born in Manhattan in 1940, Eastman was a precocious pianist, blessed with a commanding bass voice. He graduated from the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, collaborated with key musical figures like Pierre Boulez and Zubin Mehta, and taught at the University of Buffalo. But in the 1980s, after he moved back to New York City, he began spiraling into unpredictable behavior and rumored addiction. When he died in a Buffalo, N.Y., hospital in 1990, he was just 49 years old and alone. His music was scattered to the winds.

It’s only in recent years that friends and scholars have begun slowly shedding light on Eastman’s music and the blurry details of his final, erratic years — and that a newer generation of musicians has given his work a fresh look. Among those is the Los Angeles-based ensemble Wild Up, which has just released a singularly jubilant performance of Eastman’s 1974 work Femenine (pronounced feh-meh-NEEN), a mesmerizing 67-minute groove that unfolds one beautiful moment after another.

Eastman’s score for the hour-plus piece is only five pages of manuscript, and the entire work is based around one melodic building block, a two-note theme in the vibraphone that emerges from a forest of bells. For Christopher Rountree, Wild Up’s founder and artistic director, that made Femenine a kind of creative sandbox for the musicians to play in.

“It is a short score,” Rountree says. “And one that, maybe because of its brevity, encourages an amazing creative maelstrom. I love that something so gargantuan, like Femenine, can come from something so succinct.”

Composed in a minimalist style for winds, marimba, vibraphone, sleigh bells, piano and bass, Femenine was prescient for its day, premiering some two years before Steve Reich‘s lauded Music for 18 Musicians. In Wild Up’s freewheeling performance, it sounds as fresh as ever: The group adds a few bells (literally) and whistles, both to Eastman’s score and the example set by his own relaxed 1974 recording of the piece.

“The biggest liberty is the inclusion of a dozen or so long solos — all at architecturally significant moments in the piece,” Rountree explains. “Most classical players don’t grow up improvising, but most of the players in Wild Up are composers and improvisers as well.” Along the way, solos pop up for piano, cello, baritone saxophone, flugelhorn and even vocalists — a nod to Eastman’s gifts as a singer, which earned him a 1974 Grammy nomination for his arresting performance of Eight Songs for a Mad King by Peter Maxwell Davies.

Near the end of Femenine comes a characteristic Eastman curveball: From the depths of the roiling ensemble, the hymn tune “Be Thou My Vision” rises momentarily. It’s perhaps a foreshadowing of the religious pieces — One God, Buddha and Our Father — that the artist would write near the end of his short and tumultuous life.

Eastman’s career began auspiciously at the Curtis institute, where he studied with revered pianist Mieczyslaw Horoszowski at age 19, and played only his own works at his graduation recital in 1963. The details of his life in the years right after college are sketchier according to Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and his Music, a 2015 book co-edited by Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach, and still the most authoritative text on the composer. But we do know that in December 1966 he made his New York debut as a soloist at Town Hall, with a program that mostly featured his own compositions.

In the years that followed, Eastman would breach the boundaries of the classical avant-garde, a white and Eurocentric club then and now. His collaborators included John Cage, Morton Feldman and, importantly, Lukas Foss — who, in his position at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presided over the Center of the Creative and Performing Arts, a hothouse of experimental music. Eastman would have many opportunities to perform his music there over the years, and would eventually teach at the university beginning in 1970.

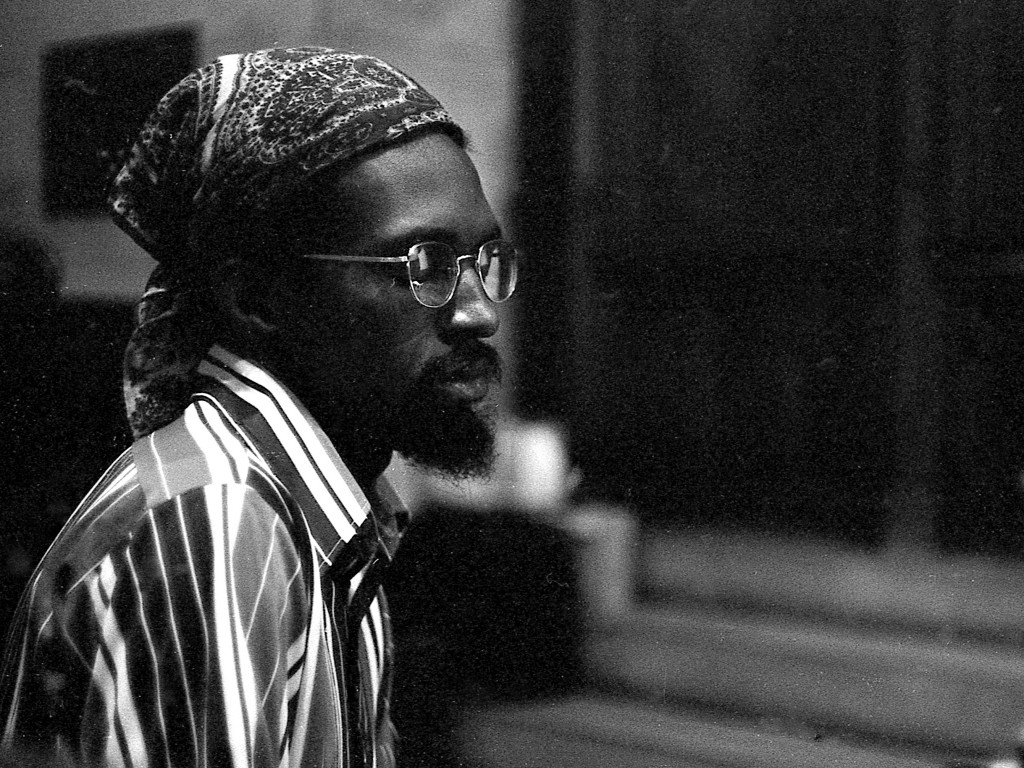

Known for his singular compositions, Julius Eastman was also a gifted vocalist, dancer and conductor. Photo: Ron Hammond/New Amsterdam Records

Early on, Eastman was characterized as shy, with few friends. But as his personality blossomed, he became the charismatic, uncompromising artist that many who knew him remember. His personal motto, which he described to the Buffalo Evening News in 1976, was “to be what I am to the fullest: Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, and a homosexual to the fullest.”

When he moved back to New York in the late ’70s, he wrote a series of enraptured works that remain his most controversial. The titles of these pieces, created in 1978 and ’79, contain slurs that most would call slap-in-the-face offensive. The music, though, mesmerizes in a non-confrontational flow of ideas. Even to presenters and audiences today, the contrast between the sound of these works and their names — Crazy Nigger, Dirty Nigger, Evil Nigger, Nigger Faggot, Gay Guerrilla — is nearly as jarring as the names themselves. At a 2019 music convention in Canada, a concert was canceled because Mary Jane Leach, a composer and friend of Eastman’s, had given a lecture wherein she discussed his works, using their full titles, preceded by a language warning.

For Eastman, using this language wasn’t only about being himself “to the fullest.” By wrapping himself in stereotyped personae, he hoped to raise questions about racism, homophobia and the power of words to provoke. He faced opposition to the titles firsthand when he presented his music at Northwestern University on Jan. 16, 1980, and introduced the works to the audience himself after a decision was made not to print the titles in the program. In the recording of that concert, released in 2005 as part of a three-disc set of his music, his introductory comments can be heard:

“Now the reason I use that particular word is because for me it has what I call a ‘basicness’ about it. That is to say, I feel that in any case, the first niggers were of course field niggers. Upon that is really the basis of the American economic system. Without field niggers you wouldn’t really have such a great and grand economy that we have. So that is what I call the first and great nigger — field niggers. And what I mean by niggers is that thing by which is fundamental, that person or thing that attains to a basicness, a fundamentalness, and eschews that thing which is superficial or, what can we say, elegant.”

As for the work itself, Eastman labeled its undulating and repetitive style “organic music,” describing the process as mainly additive with a little subtraction as needed. “They’re not exactly perfect, but there is an attempt to make every section contain all of the information of the previous sections, or else taking out information at a gradual and logical rate.” In an essay that appears in Gay Guerilla, composer and critic Kyle Gann writes that these works stand apart from the minimalist movement: “At the time, his music seemed an exciting and eccentric part of what was going on, but looking back today, his pieces sound particularly distinctive, as though he had not only absorbed minimalism, but could see into its future.”

Gradually, Eastman’s future looked increasingly grim. Friends and relatives described his behavior as unpredictable. R. Nemo Hill, once Eastman’s lover and roommate, told Packer that the artist was the architect of his own demise. “He lived the titles of his music,” Hill said. “He was the ‘crazy nigger’ and the ‘gay guerrilla.’ He was fearsome. He took aspects of his identity and foisted them on people in this provocative way.” According to Hill, Eastman never locked the doors of his apartment. Although he was robbed by one of the homeless people he knew, Hill reports that Eastman would visit the men’s shelter to give pedicures. “He was so brave. He inspired me,” Hill said.

In the early and mid-1980s, even while he was having some success composing and performing with Meredith Monk, Eastman’s troubles continued. Drinking and drugs were suspected. He was evicted from his East Village apartment, given to him by his brother, for not paying rent. City officials threw his belongings on the street, including what undoubtedly were numerous manuscripts of his music. (One of those might well have been Masculine, a companion piece to Femenine for which no score or recording has been found).

The composer George Lewis reports running into Eastman on a midtown Manhattan street in 1984, only to learn that he was staying in a homeless shelter. As the decade wore on, there was a stint as a Tower Records clerk, and rumors that he was living outdoors in Tompkins Square. By the time of his 1990 death, he mostly had slipped out of the view of his social circles. Kyle Gann was among the first to learn of it — some eight months after the fact — and wrote his belated obituary for The Village Voice.

For reasons we may never know, Eastman died far too young. But he left us much to think about — on both musical and personal terms. Long before words like “genderqueer” and “nonbinary” entered common usage, he was modeling his own kind of gender fluidity: Eastman gave performances of Femenine wearing a dress, and in a 1979 article called “The Composer as Weakling,” he hops freely between pronouns, writing: “The composer is therefore enjoined to accomplish the following: she must establish himself as a major instrumentalist, he must not wait upon a descending being, and she must become an interpreter.” Beyond exploring our authentic selves, he seemed to ask that we wave our own flags vigorously, especially in the face of opposition. It wasn’t just his startling music that was ahead of its time.

Wild Up’s new rendition of Femenine takes a page from Eastman’s personal playbook: It’s exuberant, a bit in your face, sometimes capricious, and always surprising. It’s also just the first in a series of Eastman recordings the group is planning. What kind of performance practice will develop around his music, now that more musicians are taking it up, is thrilling to imagine.

For Rountree, playing Eastman brings out strong feelings. He says that there was dancing, weeping and “lots of unheard hugging” in the studio after the final take was recorded.

“The most remarkable thing about Julius’ music is its ability to send musicians closer to themselves, to force agency on them, and pull their insides out,” Rountree says. “His pieces inspire creativity, in a totally singular way.”