A Big Push To Re-Think Miniature Paintings

ArtandSeek.net August 17, 2017 40Welcome to the Art&Seek Artist Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the personal journey of a different North Texas creative. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

Ambreen Butt in her exhibition, “I Am All What Is Left Of Me” at Dallas Contemporary. Photo: Yesi Fortuna.

Ambreen Butt is a leader in revitalizing the centuries old form of Islamic art known as miniature painting. Recently, she moved to North Texas. And she’s begun using her techniques to create giant installations. In this week’s Artist Spotlight, I learned how she confronts gargantuan issues, by starting small.

When you enter the Dallas Contemporary, the 40,000 square-foot space can make you feel tiny.

Ambreen Butt’s installation “I Am All What Is Left Of Me”at Dallas Contemporary. Photo: Kevin Todora.

This is especially true standing next to Ambreen Butt’s grand installations. The works are six feet tall and twelve feet long. They feature lavish color and ornate designs that originate from Butt’s training in the seductive art of miniature painting.

“It’s miniature, but it’s not,” explains Butt. “I went from very very small to, you know, all these crazy scales. And in the process I kept redefining my relationship to miniature painting.”

Butt is new to North Texas. Her family moved from Boston to Southlake early this year for her husband’s job.

Originally, she was from Pakistan where she graduated from the National College of Art in Lahore. The school is one of the only institutions in the world to grant degrees in miniature painting.

“You know when I chose miniature painting as my major, there were hardly any students there,” Butt says.

The traditional miniature painting technique requires enormous patience. Artists paint one tiny stroke at a time with handmade brushes made from a few squirrel hairs. Paintings are as small as 3 inches square and can take weeks to complete.

“This whole kind of [feeling], you know, [like] ‘I need to see it finished’ kept you going,” Butt says. “There’s this element of surprise too, like what it’s going to look like when it’s finished? And I think it’s because of that, I am able to do what I do today.”

Miniature paintings were very popular in Southeast Asia during the 15th and 16th centuries. But then European colonization happened.

“Miniature painting kind of flourished during the Mughal era. And after the fall of Mughal Empire, basically it became a dead art form,” says Butt.

Today the school’s program is thriving. That’s in part due to Butt. She’s one of a group of contemporary artists rethinking the sophisticated genre.

“They’ve just expanded it in different directions,” says Pieranna Cavalchini. She’s the Curator of Contemporary Art at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. “That’s the case with Ambreen, you know, with different materials, with different size. Certainly with different stories, different ideas that are in the work.”

Pieranna Cavalchini, Curator of Contemporary Art, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Photo: Pew Center for Arts & Heritage

She’s known Butt, and watched her work evolve, for nearly 15 years. And earlier this year, Cavalchini and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum commissioned Butt for a large scale installation that hung on the exterior of the museum (Listen to story here).

“So certainly the initial miniature paintings are made with paper and they’re layered, and then [she] to moved into resin and then to huge digital projections – she’s gone far.”

Butt is still inspired by miniature painting. Her pieces are large now, but they still require lots of patience. The exhibit includes a large portrait of a 5 dollar bill. It’s made from thousands of pieces of torn cash that have been rolled and precisely placed. The work’s a commentary on money and politics.

Ambreen Butt’s “In God We Trust” series, part of the exhibit “I Am All What Is Left Of Me” at Dallas Contemporary. Photo: Kevin Todora.

Justin Ludwig – curator at the Dallas Contemporary – says Butt is creating a visual language.

“So this notion of small, little delicate paintings that are often figurative – that’s not what’s happening,” says Ludwig. “She’s creating large scale installation pieces that deal with aesthetic repetition.”

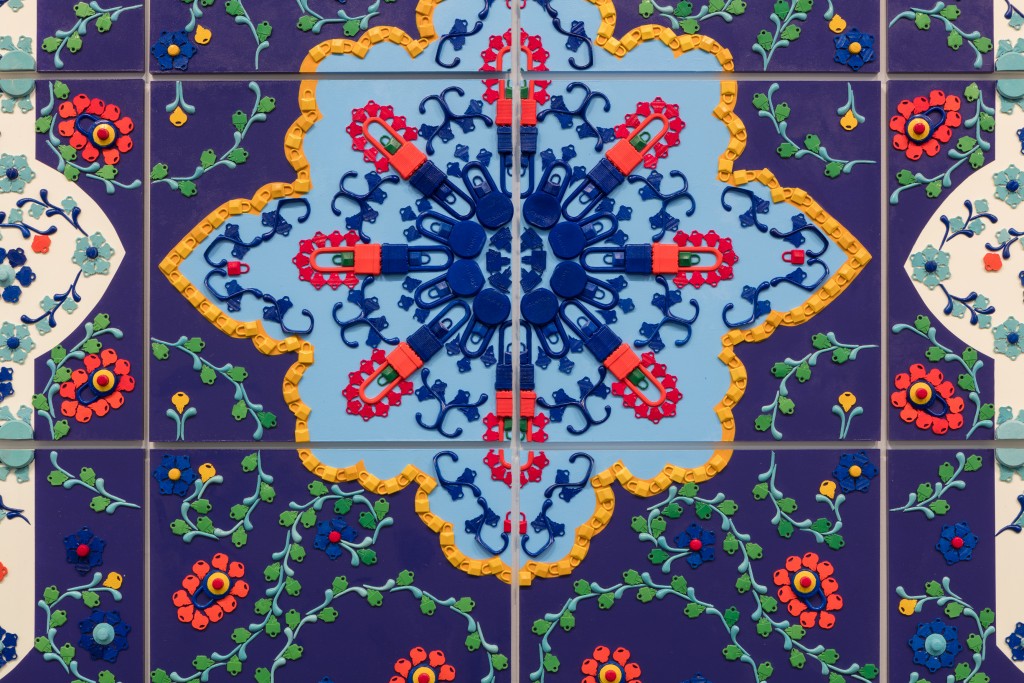

Ludwig points to three pieces that look like giant Persian rugs. They were created to hang in the US embassy in Islamabad.

Locks, keys and coat hooks decorate the pieces. They’re made out of resin and dyed bright colors. For Butt, they imply things like the US Travel Ban or some people’s fear of Middle Easterners since September 11, 2001. But she says the work doesn’t have to be read politically.

Ambreen Butt. Detail from installation at “All Am All What Is Left Of Me” at Dallas Contemporary. Photo: Kevin Todora.

“Keys!” exclaims Butt. “You know the symbolism is just so positive. And there’re more keys here. There’s only a few locks, but keys are just like openings. It’s like when you say the word ‘open’ – so much imagery comes to mind.”

She says her art reacts to political issues like terrorism, violence and political oppression. But she wants audiences to find their own meaning.

“You know if people come in and they just take it at the surface – as it’s beautiful – that’s fine,” Butt says. “They don’t have to get at exactly what I’m thinking – as long as it makes them think of something and you know it will lead somewhere.”

Butt expects her work, large or small, to evolve. She knows beauty will always be integral. And she hopes her audience will grow with her and grasp the big ideas behind her work.