A Book Hidden for 30 Years Prompts This Conversation About Dallas’ Record On Race

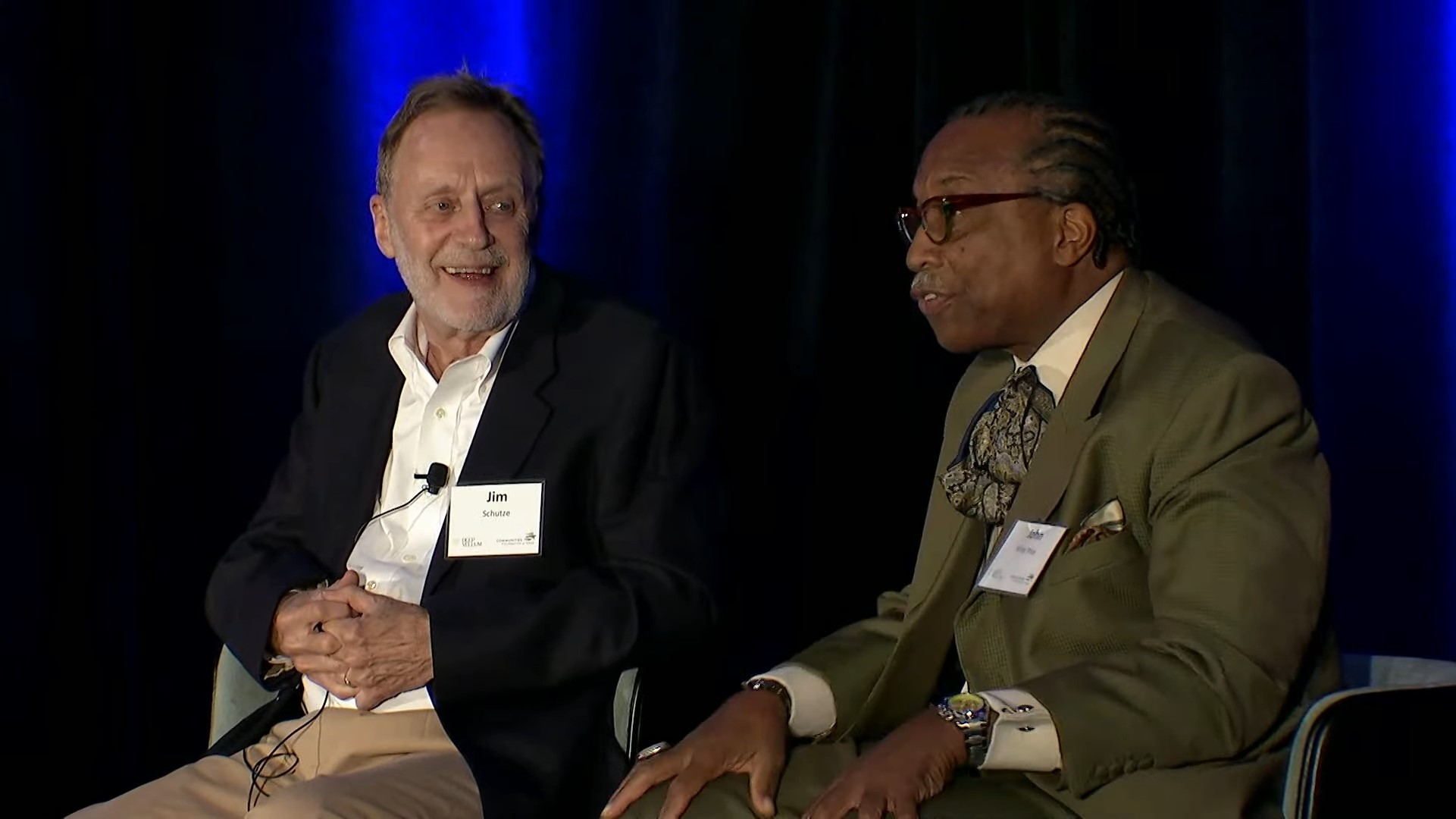

ArtandSeek.net September 14, 2021 22In the end, the two men — who’ve had their differences over the years — were accommodating. They joked with each other as they discussed their different views on, among other things, whether or not, over the past 34 years, Black people have really improved their position in Dallas’ power structure.

The occasion for Tuesday evening’s live-streamed, public conversation between author-journalist Jim Schutze and Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price was the re-release later this month of Schutze’s 1987 book, The Accommodation, the first eye-opening, even incendiary, history of race relations in Dallas. In it, Schutze lays out how the city’s powerful, white establishment worked for decades to keep segregation in place, to push Black homeowners into designated neighborhoods, to keep Black children out of the Dallas public school system –all the while making the occasional, often empty gesture toward advancing civil rights.

The conversation, moderated by Noelle LeVeaux of the Communities Foundation of Texas and held in a ballroom at the Pittman Hotel in Deep Ellum, marked Deep Vellum’s re-publishing of the book, which has been out of print and hard to find for decades. They chatted for little more than 30 minutes, but in that time, Schutze and Price came down solidly on opposite sides of the question.

Author-journalist Jim Schutze and Dallas County Commission John Wiley Price discuss the book The Accommodation.

It was a friendly disagreement. Schutze occasionally held out hope — hope in a younger, more skeptical generation, for instance. And he cited cases where, in his experience, Dallas was so far back in race relations in the ’80s that things must have improved since then. He recalled how he was summoned to appear before the Dallas Citizens Council — at the time, the all-white businessman’s committee that pretty much ran Dallas — and was asked, point blank, what do Black people want?

“And I said, so you guys know that I’m white, right?” Schutze said. Then he added, “I walked out of there, thinking, ‘Wow, this is like 1920.’ So I think we’ve moved from there.”

But Price repeatedly returned to “symbols versus substance” — in particular, civic infrastructure. Or what he called “white folk’s welfare.”

Despite repeated calls over the years for racial unity, for “Dallas together,” Price said, “we got some Black people in place [in positions of power], but when you look at the bottom line, nothing has really changed.”

With billions of dollars at stake in building schools, roads, parks, water treatment plants, he said, “look and see who has been the GC, the general contractors. I mean, anybody can take a shovel and dig a hole.” But are Black people designing the projects? Are they partners on the project?

“African-Americans, Hispanics — we have to fight for the crumbs,” Price said. “You know, Black lives cannot matter until Black economics matter.”

On this point, Schutze agreed: “The commissioner knows what he’s talking about. In 40 years of covering city hall and the schools and so on, I’ve certainly learned the real story is, ‘Who gets to build that bridge?’”

But for his part, Price hailed Schutze’s groundbreaking book for what it revealed about how Dallas was really run, why Dallas seemed stuck in a pre-civil rights era: “It’s imperative that we need to know the history . . . why Dallas has gotten like it is.”