Artist Lee Lozano: From An Unmarked Grave To Gallery Walls

ArtandSeek.net April 14, 2016 63

Lee Lozano is buried in an unmarked grave in Southland Memorial Park in Grand Prairie. Photo: Jerome Weeks

In the 1980s, Lee Lozano quit the New York art world and moved to Dallas. When she died here in 1999, Lozano was buried in an unmarked grave in Grand Prairie. But recently, her artworks have been selling for more than half-a-million dollars. And, now finally, they’re getting shown in a Dallas gallery. KERA’s Jerome Weeks says none of that is actually the strange part of Lozano’s story.

Of course, it depends on how you define ‘strange.’ Murray Smither was an art dealer in Dallas; now he’s an appraiser. He knew Lozano in her later years.

“I brought her over to my house one time,” he says, “and gave her a glass of wine, which is probably the worst thing I could have done. She began to speak to other people in the room.”

To be clear, I ask, were there were any other people in the room?

“There were no other people.”

Lee Lozano’s ‘Wave’ paintings at the Wadsworth Atheneum. Lozano stipulated the walls be painted black to display the works.

That was actually mild behavior – coming from Lozano. Smither says, in New York, if she had a beef with a gallery, she’d sleep in a box outside on the street as a protest. Having gallery visitors walk around the homeless woman to get in — it was bad for business.

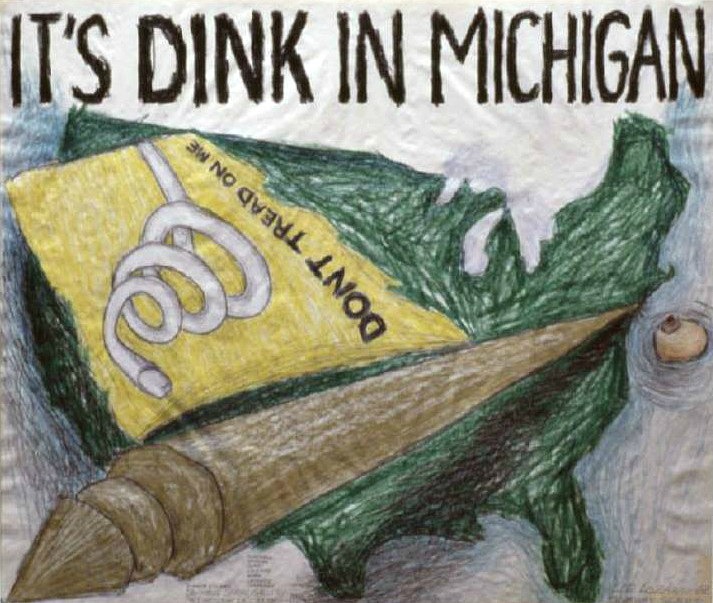

In the ’60s in New York, Lozano was an electrifying young artist — a pixie-ish character in early photos who, by all accounts, was a pixie with a sharp mind. She started as a minimalist painter — scraping paint into monochromatic waves like the grooves on a vinyl record (a celebrated series of her “Wave” paintings is in the Wadsworth Atheneum). Then she turned to aggressive drawings of tools and hardware, screws and wrenches. Then her crayon images began to get increasingly genital and come with word balloons like big ‘New Yorker’ cartoons, shouting puns and nouns and obscene, deadpan jokes.

Then she became completely disgusted with the New York art scene and more or less disappeared. By the early ’80s, she moved to Dallas. That move was partly prompted by the need to support her aging parents. They’d moved here from their home in New Jersey when her father, who’d worked in department stores, got a job in Dallas selling furniture. But by 1988, Lozano’s father filed a protective order against Lozano, who’d been living with her parents. He claimed his daughter had been attacking him, hitting and kicking.

So if Lozano were that erratic – talking to hallucinations, assaulting her father, drinking, taking drugs, possibly anorexic – why didn’t people try to get her help? Smither says it wasn’t that simple.

“It was a toss-up between whether she was performing or she was schizophrenic,” he says. “But she was also, without question, one of the brightest women I’ve ever met in my life.”

One of the four works on display at Site 131: Lee Lozano, ‘Untitled,’ no date, crayon and conte on paper.

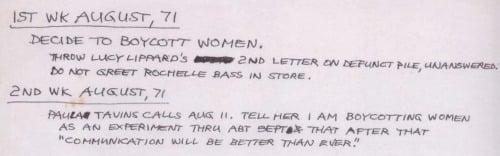

She was performing sometimes — meaning some of Lozano’s antics were actually conceptual artworks, performance pieces. Starting in New York in the ‘60s, conceptual art emphasized ideas and actions over making objects. Conceptualists blurred the lines between art and life. In 1969, Lozano began avoiding public functions at galleries; she’d come to hate them. She considered her refusal to attend an artwork; she called it her “General Strike” piece. Her “Grass Piece” involved smoking dope every day for 30 days straight and recording its effects on her art. Lozano would write out her ideas and plans in her notebooks — like the script for a play or like the instructions for a science experiment.

The use of text like this was also a conceptual form, known as ‘language pieces.’ Photi Giovanis is the owner of the New York gallery Callicoon. “What stands out to me the most was the radicality of the language pieces,” he says. Giovanis is the curator of a new Dallas show that features four small artworks by Lozano. Conceptual artists would use language as design — bold, block lettering — or the content of the words (their ‘statements’) to evoke advertising, public signs, government warnings, critical theory. And some used them like operator’s manuals. “They would write instructions,” says Giovanis. “But Lee took it to this whole other level where it just affected her life.”

The beginning of her “Boycott Piece” in Lozano’s Notebooks.

“Seek the extreme,” Lozano wrote in 1969. “That’s where all the action is.” That’s possibly her most famous statement — the kind of attractively extreme declaration that would become famous. Less famous are statements throughout her notebooks of wanting to lose her identity, to stop being an ‘artist’ — either as an ego-less entity, a being open to the cosmos, or simply just an ordinary person. In her notebooks, art could provide tremendous clarity, art was a soul-sucking business, being an artist could be a burden.

Perhaps Lozano’s most infamous conceptual work involved avoiding women. Counter-intuitively, she decided she could improve her dealings with other women by not talking with them. She tried it for a month in 1971 – she called it her ‘Boycott Piece’ – but she would work at it until she died 28 years later.

Not surprisingly, avoiding half the population complicated life for her – and for others. In Dallas – to take just one example — Murray Smither would have to cash Lozano’s checks. When Lozano needed money she’d contact her two New York art dealers — Barney Rosen and Jaap van Lehr — who had a warehouse full of her works. They’d sell some and send their friend Smither the check. But he’d also have to cash it – because Lozano refused to talk with female bank tellers.

Even Lozano’s rejection of New York and moving to Dallas — that was a conceptual work she called ‘The Dropout Piece.’ Was she still ‘dropping out’ throughout her stay in Dallas or were her actions — wandering among the bars on lower Greenville, getting drunk — more a question of emotional or mental instability? We’ll never know because she was never officially diagnosed as anything. So just how long ‘The Dropout Piece’ lasted is a matter of speculation.

“Now, I don’t want to say that she stopped making work,” says Giovanis, “because I do want to take ‘Dropout’ at its word, that it is a piece and that it was happening.”

Site 131 in the Design District. Photo: Jerome Weeks

It’s certainly possible; Lozano was nothing if not uncompromising. She often took her art to its insistent and logical conclusion. But others point to all the psychological and professional negations in her life – withdrawing from galleries, from public occasions, from women, from New York, from her parents. Why not from art?

By the time Lozano died of cervical cancer at the age of 68, New Yorkers had rediscovered the artist who, as far as they were concerned, had fallen off the end of the earth. Three gallery shows ran at the same time, drawing from different periods of her work, followed by a major exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut. Even with such renewed attention, when Joan Davidow saw a Lozano retrospective at PS. 1 in Manhattan in 2004, she was stunned.

“I’ve been spending my whole career focusing on Texas talent,” she says. “And I did not know anything about her.”

Last year, Davidow opened a new Dallas gallery, Site 131. Her gallery pairs or groups artists together to set off thematic sparks – a local Texan with a New Yorker, for instance. So when Photi Giovanis suggested a show of Lozano’s works, Davidow jumped at the idea. At last, Lozano’s art would be seen in Dallas, and as a lead-in to the Dallas Art Fair, no less, which opens Friday.

The new Site 131 show is called ‘Dropout,’ Lozano’s works are displayed with art by five other artists.

All of whom are women.

- Read more about Lee Lozano in Robert Wilonsky’s 1999 profile of her in the Dallas Observer.