Changing The Conversation Around Women And Race One Zine At A Time

ArtandSeek.net July 28, 2017 34In Dallas’ refugee-rich Vickery Meadow neighborhood, there’s a group of artists that’s determined to change the conversation around women and race. These artists are young, but age doesn’t stand in their way.

The local Trans.lation art collective in the heart of Vickery Meadow is a safe space – for immigrants, refugees and anyone in the community who wants to be heard. Today, it’s reserved for four young women: Sade Velazquez, 12; Jasmin Quintanilla, 18; Htee Shee, 17; and Rooha Haghar, 17.

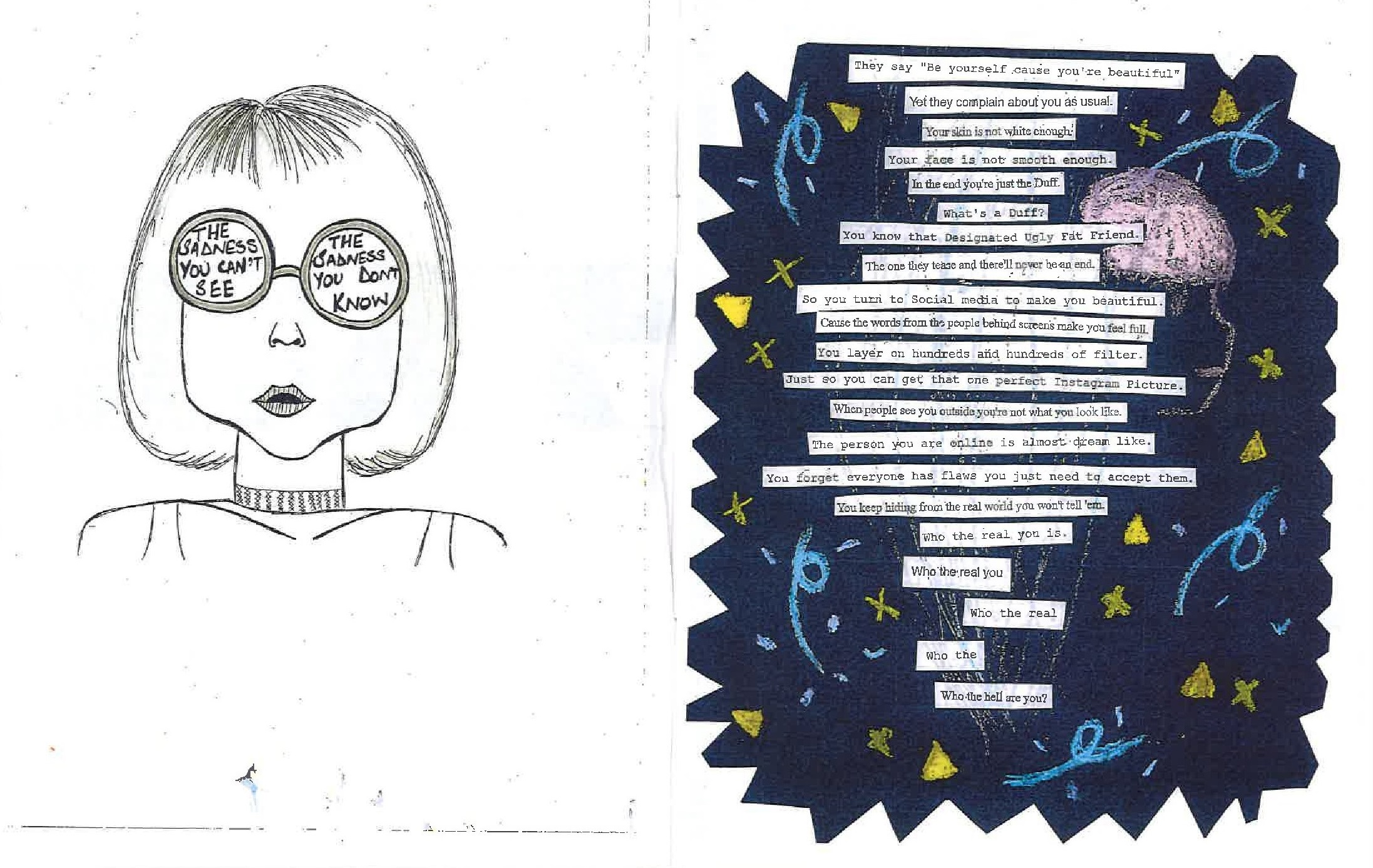

They, along with four others, came together a little over a year ago to publish “Zine-X.” It’s a small booklet – 4 by 6 inches – filled with poetry, original sketches, collages and other artworks. Jasmin Quintanilla launched the zine, inspired by a documentary about the Riot Grrl movement – the underground punk feminism of the ’90s.

“Girls around the world are never represented enough or they never get a chance to actually speak their voice,” Quintanilla said. “So ‘Zine-X’ is kind of like a way for girls in the neighborhood, who I know don’t really get a chance to speak out about things they’re uncomfortable with.”

Things like politics, racism, xenophobia and sexism – things that have touched every corner of these girls’ lives.

“I think now with the political climate, things that I create always have that message of ‘This is what I’m fighting for. This is what’s wrong,’” Quintanilla said.

A lot of that is how women and people of color are treated in public spaces. Sade Velazquez is Quintanilla’s little sister, and at age 12, she’s sick of being told that she doesn’t get it.

“Because I am young, and adults don’t take young women seriously, and especially young women my age,” she said. “They think they know what’s right for you, and that makes me upset.”

A spread in “Zine-X”.

The group has published two zines, which they’ve passed out at DaVerse Lounge in Deep Ellum. In the meantime, each girl also works on her own personal project. Velazquez, for example, is working on her own zine – one that focuses on the pivotal women of the farm labor rights movements of the ’60s.

Women like Dolores Huerta.

“A lot of people see Cesar Chavez as the full face, and I’m kind of just doing my research, looking at old articles, old photos and making artwork that represents how even in such a period like that, women were still silenced and not able to participate and allow themselves to be proud,” Velazquez said.

Gender, race and sense of place have always been an artistic focus for these girls, but since Donald Trump was elected president last fall, they’re finding it harder to feel at home.

Htee Shee is a Karen refugee from Myanmar, and her family has been in the United States for a decade. These days, though, they can’t ignore the rhetoric around refugees.

“I used to read a lot of YouTube comments, and I’m like, ‘OK, so there are people out there that are still racist that still want people who are not like them to get out of their country,’” Shee said. “And that really got to me. That really hurt me in the heart.”

She has to remind her parents this is their home, but that doesn’t stop them from worrying they’ll have to leave some day.

What really irks Rooha Haghar is the misinformation circulating about refugee resettlement.

“I’ve had teachers tell me that refugees should stop coming to America because, first, America is losing its whiteness or its American-ness,” Haghar said. “And second of all, he’s tired of paying for us with his tax money.”

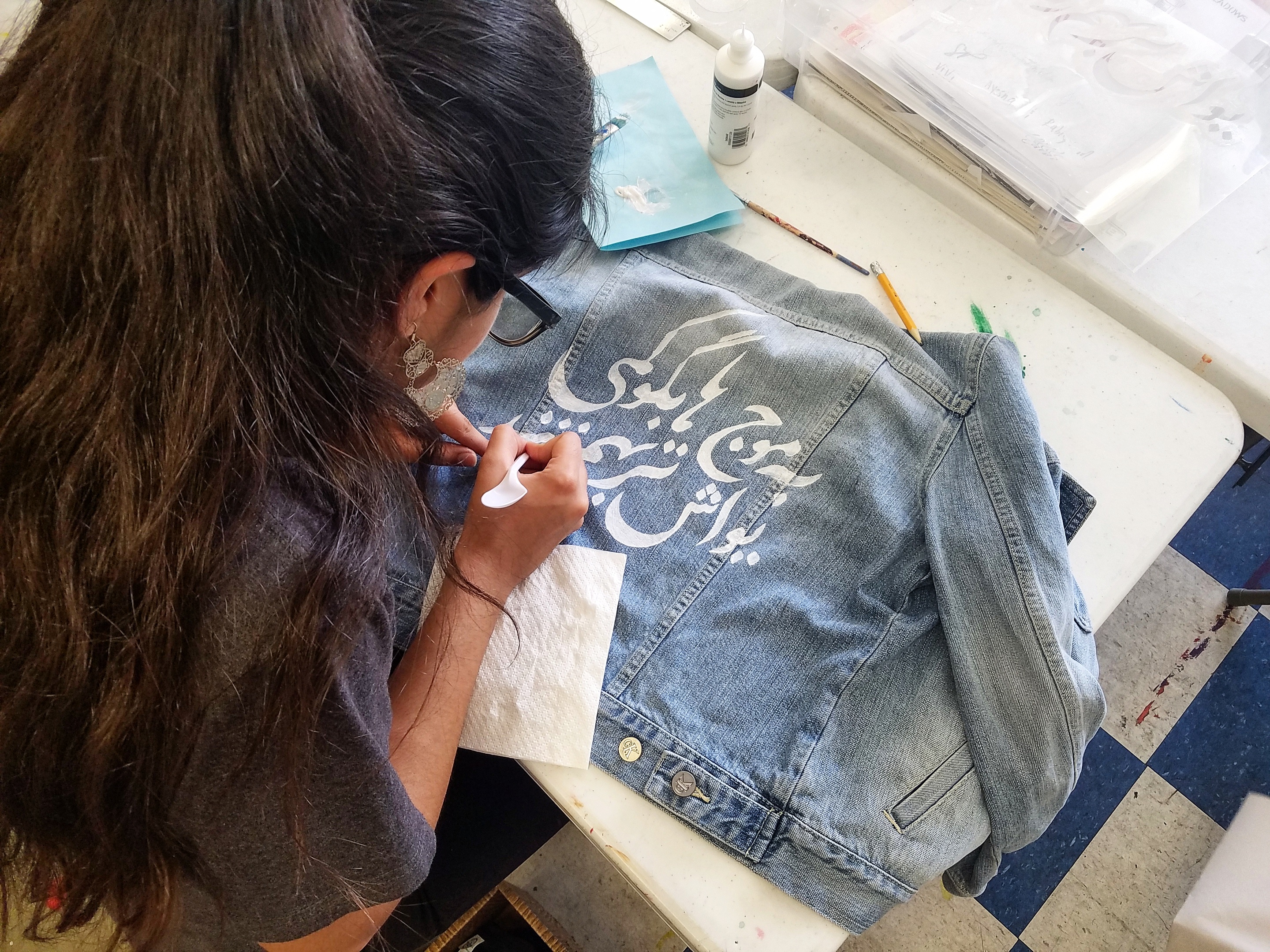

Rooha Haghar. Photo: Stephanie Kuo

Haghar came to Vickery Meadow from Iran four years ago. She said whatever taxpayer dollars she got in the beginning for resettlement, her family is already paying back through working and paying taxes. She added that those dollars went to freeing her family from religious persecution, and hopes people feel that it was money well spent. She channeled her anger and her longing for home into spray paint, applying a stencil of a poem in Farsi onto the back of a denim jacket.

“Tell the waves of the ocean to crash into each other slower,” Haghar translated.

Art like this is a way for her to stay close to her roots.

“Every morning when I wake up, I try to remember what my childhood looked like,” she said. “I know it sounds stupid, but I really don’t want to forget these things.”

For these young artists, culture and the past are inescapable. So is the present.

The election, Donald Trump, racist slurs, culture shock, immigration, pride, identity, mental illness, LGBT rights, Black Lives Matter, oppression, friendship, family, being the angry minority – all these things and more weigh on them constantly.

“It’s hard,” Quintanilla said with a long sigh. “It’s hard.

But it all serves as an important reminder: Though she be but little, she is fierce.