EG Hamilton, Best Known As The Designer of NorthPark Center, Has Died.

ArtandSeek.net May 10, 2017 48EG Hamilton, who received a lifetime achievement award for his design of NorthPark Center in 2014, has died. He was 97 and died Monday night at Clements Hospital. Hamilton had lived long enough not only to be honored by the Dallas chapter of the American Institute of Architects for his entire career but to see NorthPark’s 50th anniversary.

We re-post our portrait of Hamilton from 2014.

The Dallas chapter of the American Institute of Architects is handing out 21 awards this Thursday, including a lifetime achievement award to EG Hamilton. Hamilton co-founded the firm OMNIPLAN and he’s designed homes and office buildings from Geneva to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. But KERA’s Jerome Weeks reports North Texans know him best for one ageless landmark that turns 50 next year.

NorthPark Center can fool a visitor. The building opened in 1965 and at first sight, it may not impress, what with its simple lines and its cream-colored brick. Beyond the stores here, what’s most striking visually are the decorative plantings, the fountains and, of course, the notable artworks from the collection of the late owners, Raymond and Patsy Nasher. It can even look like the building was designed to house and encompass them. It wasn’t; the sculpture collection came later.

Architect Vel Hawes worked on different expansions at NorthPark; he has a knowledgeable eye for the building. “One thing that always strikes me about NorthPark is the light,” he says, pointing up to the clerestory along the ceiling. “These little windows along the edge plus the skylights always bring in natural light. I think that’s always important, and then the Nashers had a great sense about the placement of art. So generally it’s always placed very well.”

But a major reason NorthPark is so clear, uncluttered and harmonized is what’s not here. There are no glaring signs, no competing hodge podge of corporate styles for the many restaurants and stores. EG Hamilton designed NorthPark, and he said the decision was a collective one, made early on with Nasher to limit the palette, keep things simple.

“Up until then and since then,” says Hamilton, “each department store had its own architect, used his own materials, his own style, and the center had its own, so visually it was chaotic. But this was a goal of mine, to make this into architecture instead of a stage set. And nobody had ever done this before.”

And for Hamilton’s aesthetic to work — and to continue to work — it required Nasher to push back against the retailers’ desire to control everything about their brand and graphics. Hamilton’s design had them tightly circumscribed

“You do not touch the ‘framework’ of the building,” says Hawes. “Everything has to be approved – and these are details that will kill a deal.” Hawes recalls flying to California to meet with one retailer who wanted to cover their store with red brick. When this was denied, the company threatened not to come to NorthPark.

“Fine,” Hawes says with a laugh and a shrug. “Ray won’t let you come.”

NorthPark is a classic example of late, commercial modernism. It uses a limited range of colors and materials. It’s very spare and polished (one of the few ornamental details are the little, abstract tree icons on the corners of the storefront frames — remember, this is a ‘park’). This kind of serious, meticulous, modernist aesthetic is still best summed up by architect Mies van der Rohe’s famous declaration, “Less is more.”

Republic Towers lobby. Photo: Jerome Weeks

Hamilton calls himself not just a modernist but a minimalist. “I feel like I lived and practiced in the golden age of contemporary architecture,” he says, “which was, you know, from the twenties to maybe eighties. Mies van der Rohe was my hero. He was the greatest architect of the 20th century.”

But by the ‘70s, modernism, “the International Style,” was getting kicked around — particularly by Americans, like Tom Wolfe, who derided it as a radical, left-wing import from Europe and insufficiently yee-haw American-baroque. Architect Robert Venturi’s famous dismissal was “Less is a bore.” But perhaps what truly hobbled international modernism in the public eye — and would do the same to the fanciful post-modernism that followed it — was that developers found it could be cheap. So they made tons of cheap knockoffs of Mies’ Seagram Building and Le Corbusier’s high-rise housing.

But with the original modernists, the spareness of their designs were often countered by the luxury and modern-immediacy of their materials: marble, leather, stainless steel, chrome, bronze, polished concrete. NorthPark may seem ordinary, even modest, because it’s made of brick. The bricks actually help keep the center from being aggressively severe or purist in the high modernist, white-cube manner. They lend a soft tone to everything. And when Vel Hawes worked on the additions to the mall, he found the sand-surfaced brick Hamilton chose was subtle, richly colored – and actually expensive. The sand finish meant the bricks broke easily during production – so there were plenty of discards, raising the costs.

“We looked at any number of other bricks,” recalls Hawes,(below). “And you put them side by side, and it’s like a Rolls Royce vs. a Model T. I mean visually, it’s not nearly as handsome.”

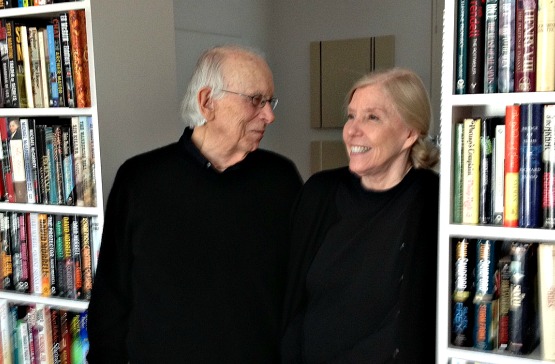

Hawes says that this simplicity, consistency and understated elegance are characteristic of Hamilton’s work, whether it’s the second Republic Tower in Dallas or the early phases of the UT Southwestern campus. Or the many homes he’s designed, such as the classic one, the ‘Hexter house’ at 3616 Crescent Avenue, or the home he designed on Abbott Avenue, where he lives with his wife EAnn Thut. She’s been the head of interiors for their designs.

“This house represents my values, my wife’s values,” Hamilton says on a tour of the house. “It’s minimalist, it’s functional and in our mind, beautiful.”

The lifetime achievement award recognizes not just Hamilton’s designs but his leadership. In 1956, with George Harrell, he established Harrell & Hamilton Architects and that morphed into the firm, OMNIPLAN. He’s also a past president of the Dallas AIA chapter. By 1990, though, he was more manager than designer at OMNIPLAN, so he and his wife left to form Hamilton Studio, and they’ve continued to work on projects, notably homes.

But leadership means more than just companies formed, positions held. For Hamilton, it’s the responsibilities architects have to more than satisfying their clients, responsibilities to the larger community that will experience their designs. “Professionalism” is what he calls it, and fears that once architects

“I really received a lot of motivation from the idea that I might be doing something worthwhile. It was more than just a business. It was almost like a religion to me.

One project the Hamiltons are working on is adding an elevator to their home, the part that’s three stories tall. It’s getting a little hard for him to get up and down all the steps.

But then, EG Hamilton is 94 years old.

EG Hamilton’s home. Photo: Jerome Weeks