Fort Worth Lynching Tour Brings Little-Known History To The Forefront

ArtandSeek.net April 12, 2021 17The tour begins in a parking lot near the Stockyards.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon in March, about 20 people gathered around Adam W. McKinney, co-founder and co-director of the arts organization DNAWORKS.

McKinney opened with a question.

“Has anyone heard of Mr. Fred Rouse before this tour?” he asked.

Not many people raised their hands. That’s not surprising, because Rouse’s history is not well known.

“I think that that’s by design,” McKinney said. “That there’s a reason why we don’t know this history. And as artists, we feel it’s important to share this history.”

Fred Rouse, a Black Stockyards worker, was lynched in 1921. The Fort Worth Lynching Tour: Honoring the Memory of Mr. Fred Rouse visits several sites associated with his murder, and is designed to push against the urge to gloss over ugly chapters in Fort Worth’s past.

In 1921, the Stockyards were not a tourist destination, but actual stockyards. Workers there were on strike, and meatpacking companies hired non-union workers like Fred Rouse to replace them.

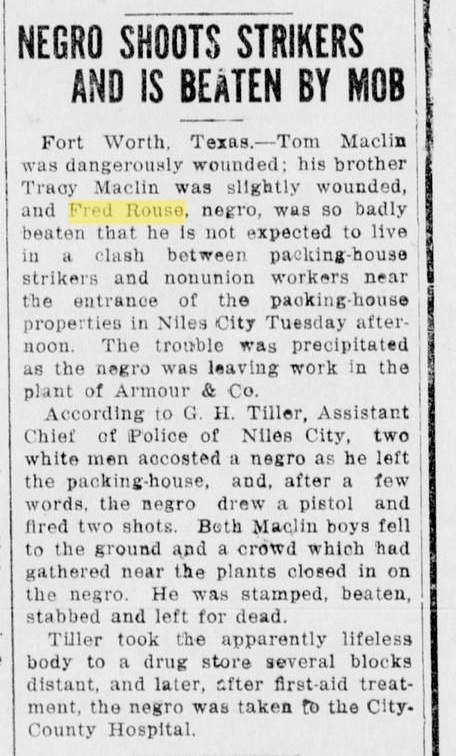

Newspaper accounts at the time claimed that during a clash outside the packinghouses, Rouse shot and injured two strikers.

The account of Rouse’s beating, published in the Plano Star Courier. At the time, the Stockyards were located in a separate town called Niles City. From UNT’s The Portal to Texas History

A mob beat Rouse, hospitalizing him. He spent several days recuperating before another mob came to the hospital, kidnapped him, shot him and hanged him from a tree.

Rouse was one of thousands of Black Americans lynched in the United States between the Civil War and World War II, according to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative.

“Terror lynchings were horrific acts of violence whose perpetrators were never held accountable. Indeed, some public spectacle lynchings were attended by the entire white community and conducted as celebratory acts of racial control and domination,” the report states.

One of the tour’s first stops is the spot where Rouse was hanged. Today, it’s an empty lot, covered in brownish grass. The tree was cut down shortly after Rouse was killed.

The other tour sites don’t seem like much at first, either. Cruising downtown on bikes, the tour group eventually came to a short brick building near the Bass Performance Hall. It used to be the City & County Hospital, where Rouse was recovering when he was abducted.

McKinney punched up an app created for the tour. It offers a performance or a bit of history associated with each site. At the hospital stop, an actor reads the account of the night nurse who turned Rouse over to the mob. McKinney played the recording over his speaker, and it echoed down the street.

“I called their attention to the fact that he had no clothes, and they replied that he would not need any. Pretty soon they came, bringing out the negro Rouse, almost in a run. The negro offered no resistance, but was groaning very much. They went out the door with him and said ‘Goodnight’ to me,” the actor read.

Today, the old hospital is part of the Bass Performance Hall complex. The basement, which McKinney said was the segregated ward for Black patients, has seen other uses since.

“We had someone come on the tour in December who said that he had his prom in the basement,” McKinney said.

Standing on the sidewalk across from the old hospital, McKinney asked the group for a word that described their thoughts so far.

For tour volunteer Brian McCarthy, the word that came to mind was “heartbreaking.”

“So little has changed in a hundred years,” McCarthy said. “Today, you can murder a man on the street in broad daylight with people filming on a phone. You don’t even have to wait ‘til midnight.”

As McCarthy pointed out, racist violence didn’t end 100 years ago. Extrajudicial killings, at the hands of white police officers or white civilians, continue today.

McKinney said in an interview that memorializing Rouse is also a way to memorialize recent victims.

“To remember Mr. Fred Rouse also means to remember Atatiana Jefferson in Fort Worth, Texas,” McKinney said. “And to remember Mr. Fred Rouse also gives us an opportunity to look through the portal at Mr. George Floyd.”

Cycling enthusiast Chiquitha Moore came on the tour, not expecting it to bring up any emotions, but it did. It made her think about all the ways acts of racism in the past affect her today.

“The feelings that are associated with that are passed down from generation to generation. Not knowingly, but it does occur,” Moore said. “It’s why you interact the way you interact. It’s why you do what you do. It’s why you are who you are in the workplace. It changes how you move through the world.”

The tour moves backwards along the route of Rouse’s lynching and ends on a grassy hill beside the Trinity River.

In the distance, cars rumble down North Main Street, past a decrepit brick warehouse. That, too, is an ugly relic. The Ku Klux Klan built it in the 1920s as an auditorium, at a time when the group was brash enough to parade around the city.

Adam W. McKinney speaks to the tour group on the hill overlooking the old KKK hall, the brick building in the distance. Photo: Miranda Suarez/KERA

“Anybody heard the Yiddish word ‘chutzpah’?” McKinney said. “Audacity.”

DNAWORKS is involved in an effort to turn the old Klan hall into a civil rights museum and performance space, named after Fred Rouse. They also plan to turn the lot where he was hanged into a memorial park.

Like the Fort Worth Lynching Tour, the goal is to take sites that hold a history of pain and destruction and turn them into places of remembrance.

Got a tip? Email Miranda Suarez at msuarez@kera.org. You can follow Miranda on Twitter @MirandaRSuarez.

Art&Seek is made possible through the generosity of our members. If you find this reporting valuable, consider making a tax-deductible gift today. Thank you.