Going Deep With The Pulitzer Prize-Winning Music Of ‘Anthracite Fields’

ArtandSeek.net April 10, 2019 18The award-wining musical composition ‘Anthracite Fields’ conveys the human consequences of the coal industry over time – from children working in mines to today’s electrical power grid. For the newest Art&Seek Spotlight, Jerome Weeks reports ‘Anthracite Fields’ is an epic, five-part musical history getting its Texas premiere Monday from the Soluna Festival.

Listen to the video above. Go ahead. Even just the first 30 seconds or so.

So, don’t you think what they’re singing – it sounds . . . silly, doesn’t it? The 24 performers in the Verdigris Ensemble, the North Texas choral group, are rehearsing ‘Anthracite Fields’ at the Royal Lane Baptist Church. The oratorio is by Julia Wolfe, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2015 for composing this.

And it sounds like … insects?

Then you learn what it’s about.

Wolfe is evoking the work of the so-called “breaker boys,” children employed in coal mines from the 1860s through the early 20th century – young boys, eight to twelve years old. Sam Brukham, director of Verdigris, explains that the breaker boys were “the young kids picking apart pieces of anthracite coal. You couldn’t do this with gloves because, you know, you couldn’t be as accurate or as quick with gloves.”

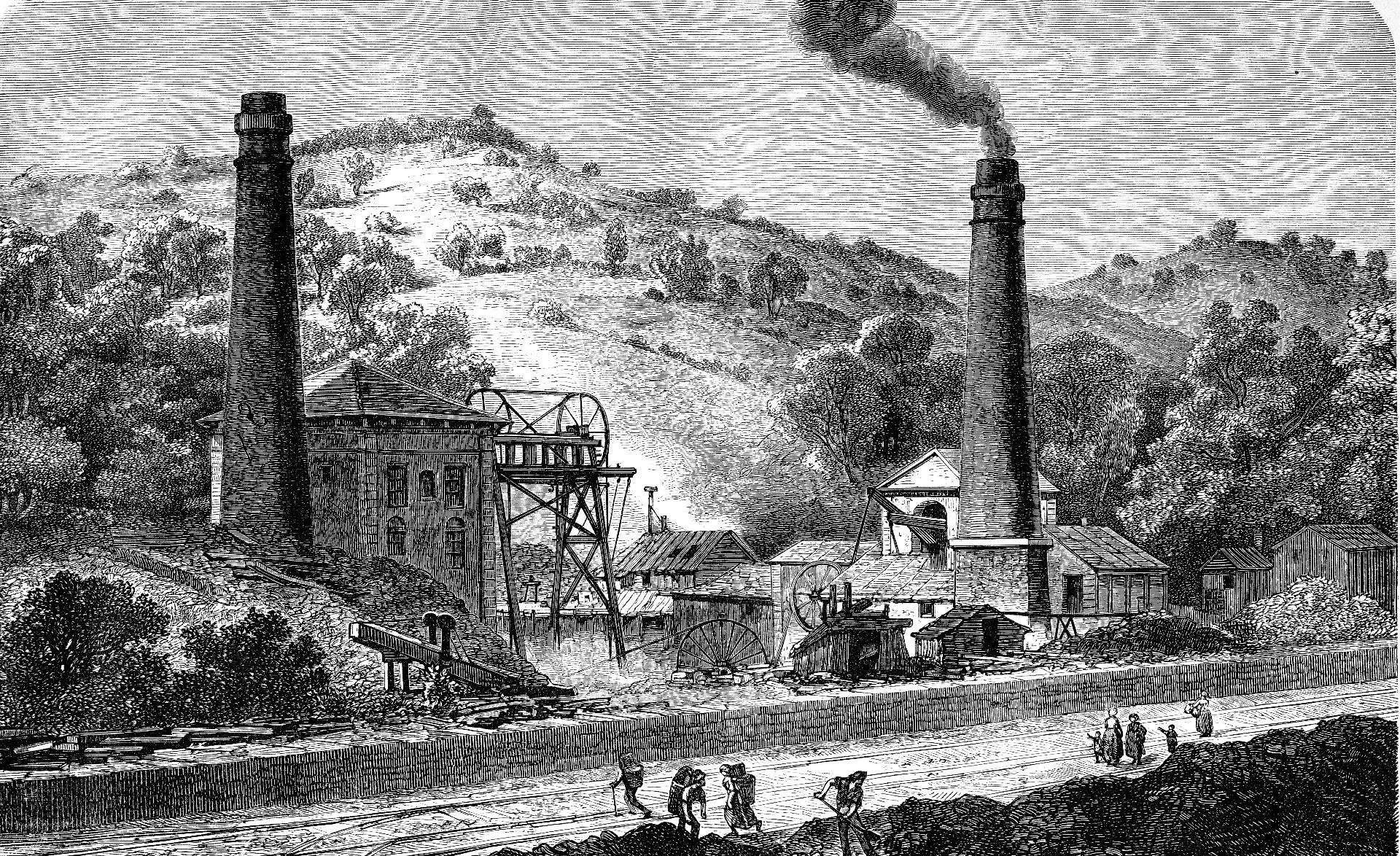

Coal pit mine, 1865. Image: Shutterstock.

So as chunks of rocks came down the conveyor belt from the mine, the breaker boys would first hammer them apart – hence, ‘breaker boys’ – and then pluck out the sharp pieces of coal from the shale and quartz – with their bare hands. They’d lose fingers, they’d lose hands. Some were even trapped by the conveyor belt, dragged into the machinery and crushed. Supervisors would have to disentangle and remove the bodies. But they’d do this only after the work shift was over. This continued in coal mines (sometimes illegally)– up through the 1920s.

Back then – before gas engines took over – everything important was fired by coal: trains, steamships, central heating, kitchen stoves. It was America’s first major energy industry and it built this country – while devastating eastern Pennsylvania. Wolfe draws on oral histories and children’s rhymes to convey the hazards of coal mining, the miners’ long fight for better pay and the many ways we still use coal for 30% of our electrical needs today.

She even includes a commercial. To promote anthracite coal, the industry created a marketing campaign around a fictional character named Phoebe Snow (not the pop singer who died in 2011). All dressed appropriately in white, Phoebe Snow boards a train bound for Buffalo.

And when she arrives, Phoebe discovers her snow-white dress is still white. That was the great advantage of anthracite: Hard and dense with carbon, it burns and leaves very little coal dust. In comparison, earlier kinds of coal – especially charcoal – coated entire cities with grit. In the case of London, the sulphur content of British coal was so high, it contributed to the infamous ‘pea soup’ fogs that proved lethal to Londoners. Anthracite makes up only 1% of the world’s coal, so it’s highly valued. And the American coal industry touted it with a slogan that may sound strangely familiar.

Anthracite was “clean coal.”

Sam Brukham conducting a rehearsal at Royal Lane Baptist Church. To perform ‘Anthracite Fields,’ Verdigris had to expand from its usual 16 members to 24. Photo: Jerome Weeks

In 2015, when Wolfe won the Pulitzer, she told NPR that she became fascinated by coal – America’s first major energy industry – and how it transformed the nation – partly because she grew up about an hour north of Philadelphia, near the Pennsylvania coal region. Yet she really knew nothing about it. “So I started to look into it,” she said. “And I thought, this is really fascinating, this life, this industry and how dependent we were on it.”

Musically, the minimalist repetitions in ‘Anthracite Fields’ sound tricky for singers – keeping the many tiny patterns and slight variations straight. Not all the music in the oratorio is composed like that. But Derrick Brown, a Verdigris singer, says what might seem like mindless chants can achieve tremendous power – like when they sing variations of the name ‘John’ over and over.

“I think she wanted to set all the names of men who’ve died in this region,” Brown says, “and the list was too long. The only way that we could narrow it down was to sing the most common name, ‘John,’ and the first syllable of their last name. And the first movement is still 20 minutes long [the movement includes more than just the ‘John’ chorus]. It’s a very humbling way to start this memorial to the industrial revolution and what we have now.”

In addition to Verdigris, six musicians from the Bang on a Can All-Stars will perform ‘Anthracite Fields.’ Bang on a Can is one of the country’s leading new music ensembles. Performers in the All-Stars have played with everyone from Philip Glass and David Byrne to Ornette Coleman.

Sam Brukham of Verdigris says, “This is a huge honor for us. And to be able to say that we worked with Bang on a Can – that has been my dream, and I didn’t think that I’d achieve it until I was 40 or 50, and here I am at age 26!”

Today, the Pennsylvania coal mines are played out, emptied of 5 million tons of coal – leaving the eastern region the poorest and sickest in the state.

Verdigris, on the other hand, is just getting started. It’s only two years old – and on Monday, they’ll sing ‘Anthracite Fields’ with the composer, MacArthur ‘genius’ grant-winner Julia Wolfe, in the audience.