Here Be Monsters: Reviewing The DTC’s ‘Frankenstein’ And Theatre Three’s ‘Jekyll & Hyde’

ArtandSeek.net February 13, 2018 79Dallas is being haunted – by some very old frights but they’ve given a new jolt. Or some dapper outfits.

Dallas theater companies have staged the two great modern myths invented by 19th-century gothic authors. The production of “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ that recently closed at Theatre Three was Goth-y gothic – a kind of mildly kinky Halloween dress-up with a few complications that lent the familiar tale some new, not-exactly-drop-your-teacup surprises. But the ‘Frankenstein’ that just opened at the Kalita Humphreys Theater – a co-production of the Dallas Theater Center and SMU – offers galvanizing gothic: It’s all harrowing shadows and deafening electro-shock, with a titanic performance by Kim Fischer (above) as the abused Creature who stalks his creator through darkness, rain and blood.

Gothic literature has typically reheated leftovers from the past. It’s no accident the gothic more or less began in 1764 with the novel, ‘The Castle of Otranto” – just as the Industrial Revolution was gearing up. Aspects of Old World aristocracy and medieval Catholicism were crumbling away in the face of giant economic, social and technological rifts. But partly as a result of their aging power, those relics – monks and church graveyards, castles and monasteries, virtuous maidens imperiled by moody, Byronic aristocrats – those relics were gaining a sexy, new aura of death, danger and the otherworldly.

Think of ‘Dracula,’ and you’ve pretty much got the gothic wrapped up in a coffin, a crucifix and an opera cape.

But Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus ‘ (1818) and Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ (1868) are distinctly modern, regardless of the garlands of gothic gloom they borrowed to cheer up the place. “Frankenstein” – adapted to the stage by Nick Dear and thunderously directed by Joel Ferrell – is the story of a man inventing another man, indeed, a superman, and then abandoning him to his fate. It’s the Garden of Eden without God.

Shelley was, in fact, criticized for her novel’s godlessness: The Creature may quote Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost,’ but when did this new Adam acquire a divinely-created soul – if all it took for Frankenstein to bring him to life were some stolen body parts and the right voltage? That’s one reason Shelley’s later revisions backed away from her revolutionary original, inserting moralizing sentiments about how ‘scientists shouldn’t play God’ – the same fears of technology and the modern world that often surge through monster movies, waving torches and pitchforks. Victor Frankenstein is an ambitious medical student defying the limitations of science and nature. But though the arrogant Frankenstein may not win many popularity contests, he is headed down the same road that leads to today’s heart transplants and contraception, reconstructive surgery and prosthetic limbs.

And, yes, to bio-engineered food and animals and even humans as well.

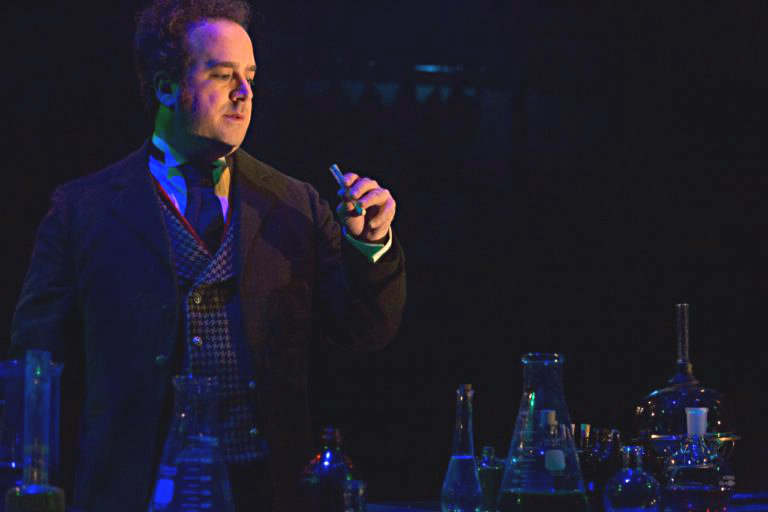

If only I could remember that fabulous mojito recipe. Michael Federico as the good doctor in Theatre Three’s ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.’ Photo: Jeffrey Schmidt

On the other hand, in “Jekyll and Hyde” – in the adaptation by playwright Jeffrey Hatcher, directed by Christie Vela at Theatre Three – a doctor finds inside himself impulses so contrary to his own enlightened, public persona they might as well be a separate creature. Which he intends to chemically distill and extract. But he ends up unleashing it instead – and enjoying it. And down that particular road lie Freudian therapy, dissociative identity disorder, anti-depressants and anti-psychotics. And yes, hallucinogenics and brain implants.

Consequently, both ‘Frankenstein’ and ‘Jekyll’ split off from the traditional gothic: They involve medical advances intended to improve humanity, whatever the bad ends they actually achieve. They point to the future and its possible transformations rather than to the cobwebbed past. They are the moment when gothic horror leaps into science fiction – and crashes on us.

Spoiler alert: Despite their good intentions, despite all the electrical zaps and colorful serums, neither doctor takes home a Nobel Prize. But what also unites ‘Frankenstein’ and ‘Jekyll’ – beyond the mad scientist figure – is the unbreakable union (and unending struggle) between the supposed hero and the supposed monster.

When Danny Boyle directed the world premiere of Nick Dear’s ‘Frankenstein’ at London’s National Theatre in 2011, he came up with a casting coup by having his two stars, Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller, alternate in the lead roles of the Creature and Victor. (On opening night at the Kalita Humphreys Theater, playwright Dear said this was Boyle’s idea. The two men had worked together for years shaping the script, but only a director or producer – no mere playwright – could cause this alignment of stars.) Boyle’s production was astonishing, dramatically inventive and justly popular. It has been one of the biggest hits of National Theatre Live’s telecasts for years now, and the next time it re-runs at the Angelika Film Center or the Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth, mark your calendar.

Double-casting like this can be a marketing gimmick or a display of actorly indulgence: One British newspaper happily declared, when Cumberbatch plays the Creature, you get to see Benedict’s bum! But twinning the actors and their roles underscored Shelley’s shifting attitudes toward Victor and his Creature. Despite the novel’s power and undeniable influence, it stumbles around a lot at first, not unlike its Creature. But all those multiple letter writers cluttering the narrative eventually lead to Victor recounting his struggles to Robert Walton, the polar explorer who found him lost on the Arctic ice. And that leads Victor to relate the time the Creature narrated his own story to him. In other words – to paraphrase Jill Lepore from a recent issue of ‘The New Yorker’ – the Creature’s story is nestled inside Victor’s, like an infant insider its mother.

Wait. It was you? Alex Organ as Victor Frankenstein and Kim Fischer as the Creature in the DTC’s ‘Frankenstein.’ Photo: Karen Almond

They’re unreliable narrators, to be sure, but they are inseparable, at times both compromised and sympathetic. Critic Lawrence Lipking in 1996 argued that this moral complexity is a chief reason ‘Frankenstein’ has spawned so many differing interpretations that don’t necessarily cancel each other: feminist ones (Victor ‘births’ a man because he wants to take on a woman’s power, and the Creature’s violent birth recalls Mary Shelley’s own harrowing difficulties with pregnancies and infant death), racialist ones (the Creature is described as having yellowish skin, distinctly non-European features and is even called a slave) and historical-political ones (the radicalism of Shelley’s father, William Godwin, identified itself with scientific rationalism – fit that into your view of the imperious Victor. Just how strongly did Mary dislike her Dad?).

Creator and Creature, Lipking argues, are on a moral seesaw throughout the novel, and it’s the the loss of this ambivalence that flaws Dear’s adaptation. Dear didn’t want to eliminate Walton and the multiple narrators but finally killed him off to simplify the storyline. On the other hand, he kept the Creature’s voice. In most movie incarnations, particularly the famous 1931 Boris Karloff film, the Creature only grunts or snarls. He’s not allowed to speak – as he does in the novel. (One could argue – as Karloff did and subsequent critics have – Karloff’s tremendous performance of mute anguish actually made the monster even more pitiable.)

To offset all this cinematic silence, Dear lets the Creature have his say. But this leads to a simplistic turning-of-the-moral-tables. The play basically indicts Frankenstein, over and over. From the ear-splitting, tortured crucifixion that opens Ferrell’s production at the Kalita, we see the Creature as an abandoned and abused child. Meanwhile, Victor, that genius, is obsessed and oblivious, the ultimate absent father. We’re back, once again, with Hollywood’s mad scientist, unconcerned about the human fallout caused by his insatiable quest for knowledge.

“Who is the real monster?” asks the DTC’s marketing campaign. That’s not even a question here. But to quote Lipking again (from ‘Frankenstein, The True Story’): “Which of us, in Frankenstein’s position, would not invite the Creature home, give him a good hot meal, plug him into ‘Sesame Street,’ enter him in the Special Olympics, fix him up with a mate and tell him how much we love him? Surely such treatment would result not only in a better Creature but a happier ending for everyone … [But this would mostly just permit liberal-minded, modern audiences a warm feeling of moral superiority.] It does not have much to do with the novel that Mary Shelley wrote. For ‘Frankenstein’ does not let its readers feel good. It presents them with genuine, insoluble problems, not with any easy way out.”

Women REALLY don’t fare well around these guys. Fischer, Jolly Abraham (face down on the bed) and Organ in ‘Frankenstein.’ Photo: Karen Almond.

To take just one insoluble problem: Should Victor create the mate the lonely Creature asks for and longs for? Or should he destroy his work-in-progress because this same Creature is a multiple murderer? (Not shown in Dear’s version: the Creature even frames a person for one of his murders.)

With Alex Organ’s absolutely chilly performance as Victor and with Fischer as a half-naked man-child crying out for justice and companionship, it’s pretty hard not to feel ‘radical empathy’ for the brutalized Other. But read Shelley’s original scene in her novel about a “demon: at the window whose grin expresses “the utmost extent of malice and treachery,” and you may find yourself feeling more hesitant about giving the Creature the chance to reproduce. Who, you might ask are we to judge the poor wretch? After all, as a species, we humans have been massively murderous.

But in that case, why would we want to unleash a super-predator upgrade of ourselves?

Critics and scholars used to advance the notion that Shelley was demonstrating Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideas of the social development of human nature in the way the Creature is mistreated and learns to hate (“Everything is good as it leaves the hands of [God]; everything degenerates in the hands of man … he disfigures everything”). But if we argue that Frankenstein (and the other people who treat the Creature cruelly) is the real monster here, then shouldn’t we forgive Frankenstein as well for wanting to kill the Creature? After all, he murdered Frankenstein’s innocent brother.

But later critics and scholars began to see quite the opposite response: Given the Creature’s violence, given the fact that he’s not actually a ‘natural’ being, “Frankenstein’ may well be Mary’s cutting critique of Rousseau and her husband Percy Shelley’s ideas on atheism, science and the innate goodness of humankind. Her novel is, in its own way, a Frankensteinian experiment: Let’s see just how well my hubbie’s ideas play out under these conditions. Whatever results she may have intended, her story and its fearsome moral implications have long since taken on a life of their own.

I must confess these doubts about Dear’s adaptation didn’t occur until I saw Ferrell’s production at the Kalita. That’s partly because, in watching the National Theatre production twice, seeing Cumberbatch and Miller flip roles, one’s sympathies and attention tended to switch back and forth, as they do in the novel. But at the Theater Center, we are on the side of the persecuted Creature all the way, no matter how much Fischer’s initial, child-like being – banging away happily on an empty bucket – turns terrifying and vengeful.

Something else the DTC production underscores: the adaptation’s homoeroticism. For decades, feminist critics have noted that women don’t fare well in Mary’s novel: Mostly, they’re either dead or soon-to-be dead. They’re martyrs to masculine ambitions. But while the victimization of the feminine ramps up the masculine nature of Victor and his experiment, it’s everyone‘s reactions to the Creature that are so telling here. A single glimpse and people recoil in disgust and hatred – all except for Victor. He extols his Creature as magnificent, even glorious.

True, the medical student is thrilled that his experiment has surpassed expectations. But the lean, muscular Fischer remains barely clothed throughout, wearing only a breechcloth and long coat, and Organ rhapsodizes about his physical presence, all the while the Creature’s scarred scalp and greasy hair make him look like some badly roughed-up rough trade. Frankenstein even decides not to kill him – standing over the body of Frankenstein’s own, freshly murdered wife (played by the easy and warm Jolly Abraham). Then, when the two men chase each other across the Arctic ice, it definitely seems their relationship has moved on from parent-and-child, scientist-and-specimen or even artist-and-artwork to something sexual and broken. It’s like the world’s worst gay divorce. On a badly planned cross-country ski vacation.

Natalie Young, Jeremy Schwarts, Michael Federico, Kia Boyer and Cameron Cobb out for a stroll in ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.’ Photo: Jeffrey Schmidt.

Having said all that – yes, I’m aware it’s a lot, there’s only 200 years of interpretations and films to get through – it must be said the DTC’s ‘Frankenstein’ is probably Ferrell’s boldest, darkest, most dramatically forceful effort since ‘Cabaret.’ Thanks in large part to Amelia Bransky’s stark but swirling set embellished by David Bengali’s flashing projections, this is one of the more sophisticated uses of the Kalita.

It takes a degree of chutzpah to try to follow Danny Boyle’s box of wonders at the National – considering that company’s bountiful rehearsal time and resources (real fire! real rain! real sparks!). Inevitably, perhaps, one senses more than a touch of over-compensation from Ferrell, the need to overwhelm: This is Hideous! This is Terrifying! the show keeps shouting at us with all the blinding lights (by Tyler Micoleau) and deafening sound design (by Ryan Rumery).

The hammering gets predictable. You just know Ferrell will give his ending a final, full-stop, symphonic crash. Yet Shelley’s novel actually finishes on a hushed, open-ended note that remarkably seems to anticipate Roy Blatty’s touching farewell soliloquy in ‘Bladerunner’: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe … All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.” Not surprisingly, replicants are sci-fi descendants of the Creature – right down to Blatty pursuing and killing his father-figure, Eldon Tyrell.

In ‘Frankenstein,” the Creature mourns in Walton’s cabin onboard his ship. He tells him, “‘I shall die [and] soon these burning miseries will be extinct. … my ashes will be swept into the sea by the winds … Farewell.’ He sprung from the cabin-window [and] was soon borne away by the waves, and lost in darkness and distance.”

The production would be even more moving, more ominous, if it ended with only darkness and the sound of wind.

Dear simplified ‘Frankenstein’ to focus on and heighten the battle between creation and creator; Jeffrey Hatcher, in contrast, has fancied up “Jekyll and Hyde,” and at Theatre Three, director Christie Vela obliges. This particular corner of Victorian London is lit up all red like an Amsterdam brothel (lighting design by Aaron Johansen).

Stevenson’s novella is a moral allegory about our divided human nature and unacknowledged drives as much as it is a horror story about a monster on a rampage. But Hatcher has divvied up the central split personality, so that the vicious Mr. Hyde is now played by four different actors. A pity no one thought to play ‘Can You See The Real Me?” from The Who’s ‘Quadrophenia.’ We can jump into Jungian archetypes or other mythic interpretations – even the way we hide behind online aliases and avatars today – but it’s worth remembering that Mr. Hyde doesn’t actually exist in Stevenson’s original story – not as any kind of separate being, that is, and certainly not as a tag team. With four different incarnations, the fact that he is simply Dr. Jekyll on a bender, the evil in Jekyll concentrated and heightened but still just Jekyll — all that gets lost. Not complicated or more interesting, just … diluted. When Cameron Cobb or Kia Nicole Boyer is playing Hyde, for instance, he doesn’t look all that “repulsive” or “abominable,” as he’s described. One could certainly see the logic in making evil attractive. If it weren’t, who’d ever do it?

Jeremy Schwartz and Mr. Hyde in Theatre Three’s ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.’ Photo: Jeffrey Schmidt.

But that’s not what Stevenson’s story is about. In 1868, he didn’t have the psychiatric understanding of repression to explain Jekyll’s compulsive need to create an alter ego that runs brutally amok. But he sensed the bifurcation in Victorian England – between London’s rampant child prostitution on the one hand, and Victorian ideas of progress and propriety on the other. In fact, Stevenson rejected a later interpretation of his story that linked it to a real-life case of ‘multiple personality disorder.’ That’s too easy, too individual.

The lack of any pat, inner explanation for Jekyll’s actions only makes ‘The Strange Case’ more applicable to Stevenson’s general time and place. Unlike the multiple narrators in Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein,’ Stevenson’s tale has a calm, clear and unassertive narrative style because it’s told from the point of view of Jekyll’s good friend and unflappable lawyer, Gabriel Utterson (the kind of fellow who admonishes others with “tut, tut”). This entire approach — and its resulting tone — is important. It’s a basic element Hatcher’s adaptation lacks – at least in Vela’s hands: Victorian restraint. Stevenson’s prose alone conveys an entire world view of stability and accepted behavior that gets turned upside-down and inside-out when Utterson discovers what his friend has done — indeed, by implication, what any of us, even the best of us, is capable of in private.

Which is why Dr. Henry Jekyll needs to be if not the height of honor and reason then certainly what was once meant by a “true gentleman,” someone whose name is followed by “M.D., D.C.L., L.L.D. and F.R.S.” (doctor of medicine, doctor of civil law, doctor of laws and Fellow of the Royal Society). If he weren’t so handsome and tall, as Stevenson describes, Jekyll would practically sag under all the public respectability and distinction those initials confer.

We need this because Hyde thrives in stark contrast to everything Jekyll represents: He’s unreasoning, cruel, impulsive, uncaring, self-indulgent, violent. He’s even described as “repulsive” to Jekyll’s good looks. But the various crimes and murders Hyde commits in Stevenson’s story are essentially unmotivated – he’s just that bad. But such random malignancy doesn’t provide much narrative depth or interest. So Hatcher gives Jekyll, played by Michael Federico, a reason to murder Sir Danvers Carew. His Jekyll is yet another one of our medical forensic geniuses, an Asperger-y compulsive like Dr. House or the Benedict Cumberbatch version of Sherlock Holmes. During a homicide dissection in an operating theater, Jekyll can’t help but make Carew look like a fool and a perv, and Carew (Robert Gemaehlich) responds with huffing threats of dismissal and exposure. So farewell, Carew.

In a program note, Federico even declares the obsessive Jekyll “kind of insane.” But if he starts utterly neurotic, then turning into Hyde really isn’t that much of a walk on the wild side, is it? And Stevenson’s moral allegory isn’t all that scary or all that applicable to the rest of us. You know, us normal, sane, healthy, proper folks in the seats.

If I were asked to cast any local actor to play Mr. Hyde, my sole and immediate choice would Vela’s: Jeremy Schwartz. And he certainly doesn’t disappoint here. Simply by his size, his presence, his manner, Schwartz’ Hyde is a thug to be reckoned with. Or best avoided. But he’s only one-fourth of this Hyde, so that chilling effect is watered down, and watered down even more when he also plays the reasonable Mr. Utterson.

Ironically enough, this actually makes Schwartz’ two-sided performance more succinctly like ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ than anything else in Hatcher’s stage adaptation.