Panning For Gold: A Musical Instrument Aids One Man’s Recovery

ArtandSeek.net June 27, 2019 31You can go to a Denton coffeehouse and listen to a musician playing an instrument that looks like a laptop flying saucer. Art & Seek’s Jerome Weeks reports it’s known as a handpan – and the odd invention and the musician playing it have more than the usual relationship between performer and instrument.

Gracen Lee playing 1:

Gracen Lee playing 2:

Gracen Lee is a 55-year-old Korean immigrant who lives in Denton. Gracen is his stage name as a musician. His given name is Harold Lee. Two years ago, his life more or less blew apart.

“I experienced the death of my marriage,” he says, “and the death of my father in about a three-week period.”

Lee’s father worked for Gulf Oil. He moved the family from South Korea to Houston in 1981. Lee eventually combined his computing skills and the architecture training he got at UT-Austin to create virtual buildings for video games. Lee, his wife and their three sons moved to North Texas, where his wife has family, and Lee got into retail sales.

But then came the divorce and the death of his father in 2017. Lee spent his nights, depressed, scrolling through YouTube videos. Until he came across a person playing something that looked like a steel clamshell.

“Within about 45 seconds into watching that video,” he recalls, “I became obsessed. I stayed up all night long, watching different videos.”

Lee wanted to find one of these instruments, learn how to play it. The sound the instrument makes is clearly percussive. But it’s also ethereal and dreamy, almost as if it’s some ancient temple chime from Asia. Turns out, the thing was invented less than 20 years ago by two artists, Felix Rohner and Sabina Schärer – in Switzerland.

“And they patented it and they called it ‘hang’ [pronounced HOH-ng]” Lee says. “And my understanding is that ‘hang’ in that particular dialect in Switzerland means ‘hand.’ They also decided that they were gonna form a company called PANArt.”

An original, first-generation ‘Hang’ drum. Photo: Handpan Guru

The story of the hang and how Gracen Lee became North Texas’ leading – that is, perhaps only – public handpan player – both stories are unusual. And connected.

You may have actually seen a hang – it was just called something else. In America, it’s often known as a handpan. But it’s also a hang drum or a steel pan or even a pantam. The original Swiss name, ‘hang,’ is a trademarked term by PANArt – but only in Switzerland. Still, to avoid patent and copyright infringement issues, in 2007, the American company, Pantheon Steel, came up with the name ‘handpan’ (an Israeli distributor later used ‘pantam’). And although the two Swiss artists invented the hang, they clearly drew on the technology inherent in a popular, earlier, folk-created instrument from Trinidad: the steel drum. Technically, steel drums, hand pans and xylophones all belong to the ‘idiophone’ family of instruments. They’re all made of metal that you bang on to cause vibrations.

“A handpan is basically an inverted steel drum,” says Bryant Evangelista. “A handpan is composed of two shells that are glued.” Where a steel drum is open-bottomed – the better to be loud and ringing – the handpan is a sealed shell, and that bottom half helps give the drum its unique, softer resonance.

Bryant Evangelista is an Austin handpan maker, perhaps the only one in Texas. His company is called Pansnap Music. Each of his handpans is hammered out, hand-made. In fact, he got his start making steel drums – sweating over them, hammering them out by himself with a steel sledge. Now he uses an auto-hammer.

“If you saw my workshop today,” he says with a laugh, “all you’d see are hammers everywhere.”

Bryant Evangelista in his Austin shop. Photo: courtesy Pansnap Music.

Musically, the handpan sounds more mellow than the typical island steel drum; it lacks the sharp, pinging tones, even though it still sounds gently metallic. Partly, that’s because you don’t traditionally play the handpan with drum mallets, just your bare hands. And it’s partly because you usually hold it against your body, most often in your lap but sometimes with a guitar strap slinging it across your hip. Your body softens the sound.

“You’re connected with this instrument,” Evangelista says, “and when you play it, you feel the resonance of the drum.”

Actually, some small companies have even developed fabric or open-bottomed handpan stands to ease any back or leg strain – while still preserving the instrument’s sound.

But when it came to Lee’s quest to find and play the thing he saw on YouTube, he faced two major hurdles. First, he didn’t know much about music – at all. He can’t read sheet music. He never really learned an instrument, although he remembers noodling on a piano when he was a child. In fact, when Lee finally tracked down, purchased and received his first handpan in the mail, it came with a slip of paper in the package. It said ‘D minor.’ Lee says he didn’t even know what that meant. Because he’d bought the instrument on sale from a California shop that was dumping its line of handpans, he assumed ‘D minor’ was a grade – he’d bought some leftover, sub-par piece of metal.

In truth, handpans – like most other metal percussion instruments (chimes and bells) – are tuned to a particular pitch. By pure coincidence, Lee’s minor-key, supposedly ‘low-grade’ handpan perfectly suited his somber, reflective inclinations.

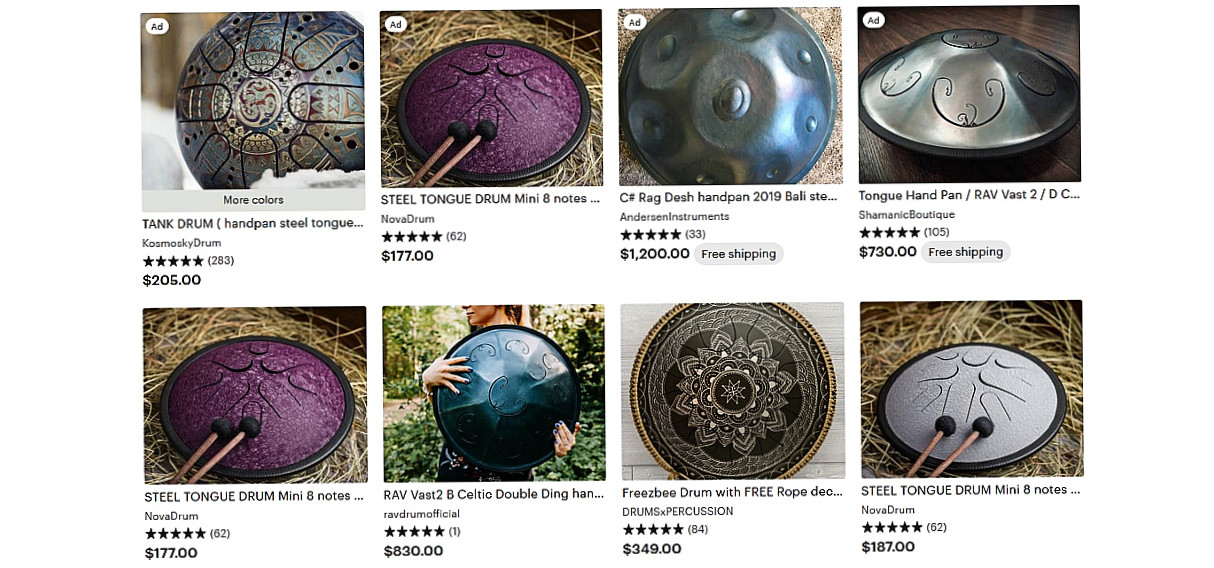

A small sample of the many colorful variations of the handpan available just on Etsy.

But Evangelista says Lee’s lack of musical training is actually pretty common among handpan players. And it has not proven to be a serious impediment. That’s one of the metal drum’s appeals.

“The learning curve is not a lot,” he says. “The way the handpan is laid out, it’s very easy to make music.”

You just thwack it with your thumb or tap it with your fingers. You don’t have to master complex fingering techniques – like with a piano, guitar or violin. And it’s easy enough to experiment with. Different spots on the shell produce different notes or tones (that’s what the ‘dimples’ are for). And you can even learn to dampen or heighten the “sustain,” that is, the reverberation.

But the other difficulty facing Lee was just getting his hands on one. PANArt had consciously kept its business small-scale, tightly controlled and artisanal in nature. For Rohner and Schärer, the Swiss inventors, their hang was a work of art, a sound sculpture. They resisted attempts to mass-produce it or sell their company to a conglomerate. This kept the instruments’ quality high but their instruments rare. As an example of PANArt’s anti-corporate thinking, Lee says early adopters had to write an essay to the company, explaining their thinking about music, what they wanted to do with the hang, etc. – all before they were permitted to buy one.

Then, in 2013, PANArt stopped producing the hang. Except in isolated cases. Instead, the company has moved on to other sound sculptures, concentrating on developing and manufacturing new variations of metal ‘talking pots.’

Lee’s second handpan, which he bought from Pansnap in Austin. Photo: Jerome Weeks

With PANArt ceasing production, the price of a first-generation hang “went up tremendously,” Lee says. “I actually saw one for, like, $17, 000 on eBay.”

Currently, there are less than a handful up for auction on the website, ranging in their asking price from $4,300 to $8,500. Back in 2001, the cost of those first hangs was $400.

Lee eventually found a lower-priced handpan online. Different sites nowadays offer hundreds of elaborately scrolled, engraved and torch-colored variations as well as what amount to cheap knockoffs. They’re now called tongue drums, tank drums, moon drums, vibe drums even ‘freezbee’ drums (echoing ‘Frisbee’). But when PANArt stopped making its hang, that also left the market open for serious craftsmen like Evangelista in Austin – which is where Lee got his second drum, this time a brighter, major-scaled one called a Solaris.

Since its invention, the handpan has gained a distinctly New Age-y vibe. Some are even called “chakra drums.” That’s partly because of the hang’s artisanal, anti-corporate origins, its relative simplicity and seemingly ‘native’ or esoteric aura. Many are sold with Celtic, Arabic or Asian artwork on them – none of which actually has much to do with the instrument, its design or its Swiss origins.

But the main appeal is perhaps the obvious one: The handpan’s warm, soothing sounds seem to suit places like spas, yoga studios and meditational retreats.

But if anyone could attest to the beneficial, even spiritual, effects of playing the handpan, it would be Gracen Lee.

“My playing the handpan – it has less to do with musicianship but it has more to do with my pain,” he says. “This is how I was able to process my loss and my grief.”

He says playing the handpan has helped his own spiritual recovery. That’s why a man with the given name Harold Lee started calling himself Gracen. He wanted to express his gratitude to a higher power.

When he plays the hand pan, Lee explains, he feels as though he himself is an instrument – of God.