Racing Across Texas – In A Series of Stolen Cars

ArtandSeek.net October 12, 2018 34Welcome to the Art&Seek Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the cultural creativity happening in North Texas. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists and artworks we’ve chronicled.

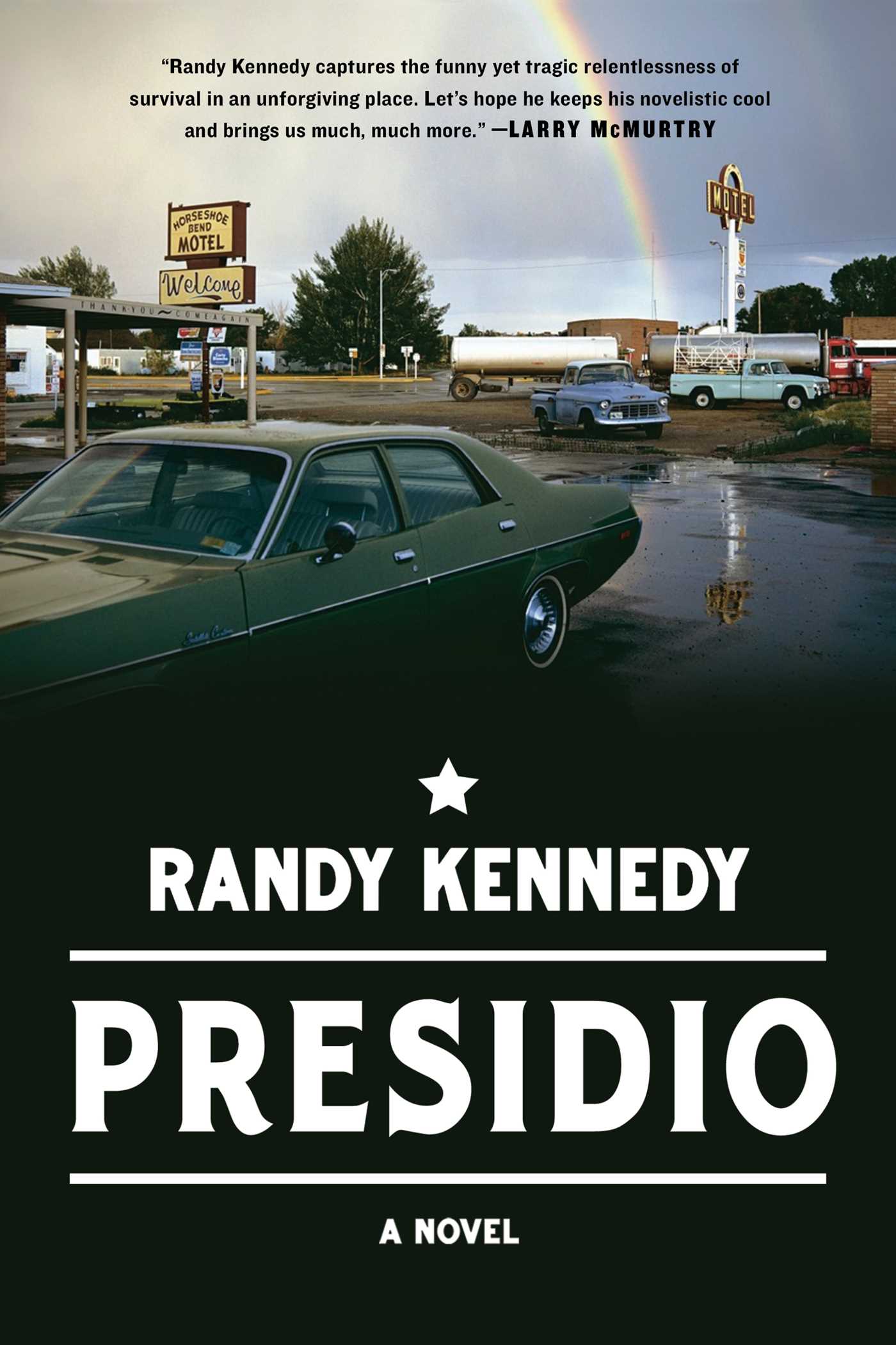

Randy Kennedy’s debut novel, called ‘Presidio,’‘ has gotten excited reviews – including one in ‘The New York Times’ by Lee Child, creator of the popular Jack Reacher thrillers. ‘Presidio’ tracks a car thief and his brother as they race across West Texas. For the Art & Seek Spotlight, we sat down with Kennedy to ask why West Texas? And why a car thief who really isn’t stealing cars for the money?

Our extended conversation, edited for brevity and clarity:

Randy Kennedy, welcome to KERA.

Thanks for having me.

Now, you grew up in West Texas, but you’ve had a solid career at ‘The New York Times’ and now with a New York art gallery. So why return to Nowhere, West Texas, to write your first novel?

Partly, it’s a case of ‘write what you know.’ But I had worked on a bunch of short stories for years and years that were about these two brothers in West Texas, one of whom was a car thief. And there was something about a car thief in that part of West Texas that was very attractive to me. And I also thought, given what my character does – which is he’s a regular car thief and then he kind of tips over the edge and he tries to disappear and not have any possessions and have no identity. And I thought, you really – probably in the 1970s in a place as sparsely populated as West Texas – you really could have gotten away with that.

And also, I’ve been in New York now for 28 years, but the longer I’ve been away from that part of Texas, I began to appreciate its starkness and its pretty strange history. You know, it’s just a freakishly flat part of the world. There aren’t that many places that flat.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

In doing research for this novel, I went back and read the accounts of Coronado’s expedition, when they came through that part of Texas [in 1541]. There was an account written by a soldier who went on the expedition, and over and over, he wrote about how the land actually terrified them. You’d wander ten minutes from camp, and if you couldn’t see it, you couldn’t find it. You were lost – there were no landmarks, not a tree, nothing to follow. They compared it to being lost on the ocean. That’s the only reference they had. They’d never seen anything like it.

And also, I think there have not been many short stories or novels written about the Panhandle proper. Larry McMurtry’s Thalia is kind of nearby but it’s really east of the Panhandle.

Texas noir – crime novels that really use Texas as a setting – they’re now a tradition, not just in novels but films. There’s the bleak landscape you mention, and the hard loner who’s often emotionally damaged like Troy, your car thief. Characters almost as barren as the land. So it’s hard to read ‘Presidio’ and not hear something like Ry Cooder’s mournful slide-guitar music from the movie, ‘Paris, Texas.’

Was any of that an influence on your writing?

I didn’t think of it very much as a thriller, although there are people who break the law and are trying not to get caught. But it was more just watching Westerns, y’know, especially the drifter sub-genre. You know, I kind of think of it more in the realm of short stories by Denis Johnson that are about people who don’t have very many options and they’re just trying to make it work.

They don’t fit in, so they go looking for some place where they do. Somehow.

They don’t fit in and they’re trying to maybe find some meaning in their lives.

I’m originally from Detroit, from a car family. And just about every car Troy steals – I couldn’t help but laugh sometimes. Even in the ’70s, they were pretty much down as junk. Obviously, he doesn’t want to attract attention with some hot car. He’s not in ‘Vanishing Point’ with a hemi Challenger. But I mean, a wood-paneled Ford station wagon? Troy is really not boosting these cars for the money.

No, he’s not [laughs]. I’m really not a car guy, but my father could take apart just about any car and put it back together. And yes, I deliberately chose makes of cars, all of them are no longer in production. It was a very special time, that period, with cars that say a lot about America, America before the gas crisis.

With this kind of driving the highways going on in a novel or a film, there’s often the traditional American ‘romance with the open road.’ All the possibilities that exist out there; you can just keep going and change your life. But here, even as you describe the beauty of the open sky, there’s a sense of futility. Troy and his brother can drive as much as they want, as fast as they can – and the same troubles are waiting.

Yeah, when I was growing up in that part of West Texas, there was a part of me that really liked driving because you could be out by yourself. It was an escape for a while anyway. And the sunsets could be beautiful. But often driving was just drudgery. It was like, ‘I know I have six more hours to get where I’m going, and my ass hurts. But I just gotta get there.’

Consciously or unconsciously, they just have this feeling ‘We’re never going to get there.’ You know, [the Marfa minimalist sculptor] Donald Judd had this great quote. It’s something like, ‘Texas is miles and miles of nowhere to go.’

Whether it’s a drifter in a Western or the hard-boiled character in a Texas noir novel, the thing you do in ‘Presidio’ that’s so different from either of those genres is you let us inside Troy. We actually read his diary entries.

And the genesis of that was that I had written these short stories, and they were almost all in the first person – of this car thief who couldn’t live in society anymore. Then, when it began to make more sense as a novel, those short stories stayed in there as his journal. And I don’t think of this as a heavy ‘meta’ sort of novel, but Troy has a lot of time on his hands. When he’s not stealing cars or breaking into motel rooms, he doesn’t have much to do. So in keeping this little journal on motel stationery or whatever bits of paper he can find, he essentially ends up becoming a writer.

Just mostly for himself – but the conceit of this is he’s kind of a writer.

Without his journal entries, Troy would be completely opaque to us, an enigma, just another sullen loner. But with his journal, there’s actually this almost spiritual or religious thread through ‘Presidio.’ He’s practically Puritanical in the way he doesn’t keep anything he takes or maintain any relationship – as if this world is all corrupting somehow. He’s a car thief who rejects people and money.

Right, right. I didn’t want him to be like a ghost, something mythic. I didn’t want him to be the Clint Eastwood character in ‘High Plains Drifter,’ who you don’t know whether he actually exists or not.

I don’t really know where this person who really wants to renounce all personal possessions in a kind of a monastic way came to be. I saw him as something of a holy fool, a medieval holy fool, who rejects this world, sees through it and tries to live outside it somehow. He’s like the Fool in ‘King Lear.’

Without the puns and jokes.

Yes. And then when I decided to bring a third character into the car – because I felt there needed to be another character besides just Troy and his brother in the car – it became this Mennonite.

And that’s the other unusual thing about ‘Presidio.’ This has to be the only Texas novel I’ve read that features Mennonites. Why this unusual sect?

In the part of West Texas where I grew up, near Lubbock, there were Mennonites who lived around us who were often farmhands. And I was always fascinated by them because I grew up as a Southern Baptist, and I remember at some point sort of realizing they were a kind of Baptist but whatever Baptist they were caused them to separate themselves completely from modern life.

And then I learned about the great colonies of Mennonites in Chihuahua, in the desert in Mexico. I just became fascinated with their displacement – you know, they moved all the way from Canada to Mexico at the beginning of the last century to have freedom from interference, to just live the way they wanted to live.

And there was just something about that austere life and this wandering, there were affinities to Troy.