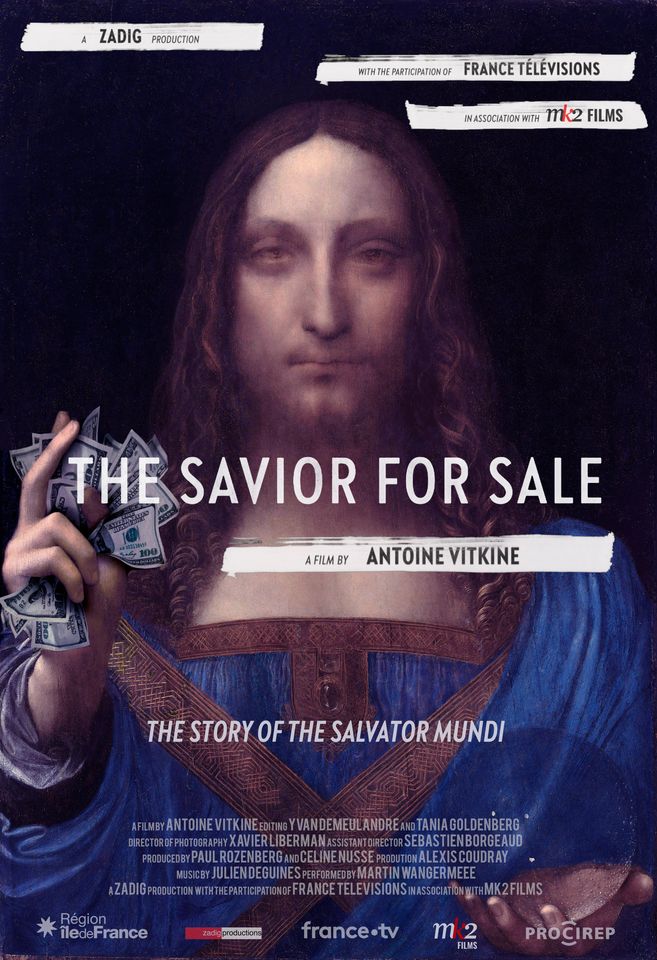

Remember ‘Salvator Mundi,’ That Da Vinci Painting The DMA Wanted To Buy?

ArtandSeek.net April 9, 2021 24The Art Newspaper has a story about a new French film, The Savior for Sale by director Antoine Vitkine, which delves into why the Louvre’s 2019 blockbuster exhibition of Leonardo’s works ultimately lacked Salvator Mundi, the contested portrait of Jesus that was sold for $450 million, the largest amount ever paid for an artwork. The film, which premieres on French television April 13th, includes interviews about how Saudi Arabia pulled the painting from the museum show when the Louvre’s experts concluded that, at most, da Vinci “had a hand in it.”

In 2012, former Dallas Museum of Art director Maxwell Anderson reportedly had the 15th-century painting at the DMA and was trying to raise enough money to purchase it for the museum’s permanent collection. At the time, the price was supposedly $200 million. Anderson’s effort was not successful — and the painting’s then-owners moved on to Christie’s and what became a historic and controversial auction in 2017.

In 2012, former Dallas Museum of Art director Maxwell Anderson reportedly had the 15th-century painting at the DMA and was trying to raise enough money to purchase it for the museum’s permanent collection. At the time, the price was supposedly $200 million. Anderson’s effort was not successful — and the painting’s then-owners moved on to Christie’s and what became a historic and controversial auction in 2017.

The attribution has remained a matter of extensive debate – with some declaring Anderson’s effort at acquiring a work by the greatest Old Master ‘vindicated,’ while other experts argued otherwise. When it came to the Louvre’s exhibition in 2019, The Art Newspaper reports, “An anonymous senior official in French President Emmanuel Macron’s government, codenamed “Jacques,” tells Vitkine that the Louvre’s extensive scientific examination of the painting, conducted in secret, concluded that Leonardo da Vinci himself “only contributed” to the picture, and that its “authenticity” could not be confirmed.”

This was much more than a quibble among art specialists: The Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), had purchased the picture for nearly half-a-billion dollars at a Christie’s auction, where it was sold as an authentic Leonardo — “the male Mona Lisa.” What’s more, France was negotiating a ten-year deal, “potentially worth tens of billions of euros, that gives France an exclusive role to develop the Al-Ula province” as a major cultural site and tourist destination.

The Art Newspaper quotes a go-between in the negotiations over the painting who speaks in The Savior for Sale:

It was very brave of the Louvre to say, ‘this is what we think, many others may think differently, but this is what we think as a scientific reflection on the painting’. I trust the director of the Louvre, I follow the scientists, it’s not for me to say. I have confidence in the Louvre, it’s a question of confidence, the director of the Louvre decides where the painting is going to be shown and in what context.

Unsurprisingly, when this was communicated to the Saudi officials, they were not happy.

But The Art Newspaper report goes on to what’s still an unsolved mystery in the painting’s tangled history: Why, then, did the Louvre issue a book detailing its scientific and historical studies, a book whose preface declares the test results “confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci”?

The Louvre then suppressed the book — because it was meant to accompany the now Salvator-less exhibition, and the Louvre is not permitted to opine about works not in its galleries. The Louvre has not commented on the book nor on The Savior for Sale.

Martin Kemp, the British art historian, the most important expert to attribute Salvator Mundi to da Vinci, has said that Christie’s overstated the painting’s provenance “absolutely.” In the film, he says, “I wouldn’t stick my neck out unless I was reasonably confident, but you can always be wrong. If I’m wrong, nobody died—somebody lost a lot of money.”