Review: ‘An Octoroon’ At Stage West

ArtandSeek.net September 11, 2018 70The Obie Award-winning play, ‘An Octoroon’ – getting its area premiere from Stage West – is an audacious, satiric riff on racial disguise and identity, mask and mockery from African-American playwright Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins. It’s a play-within-a-play, a comic provocation about the play-acting that has made up so much of black and white history in America.

To give a quick idea of the racial mixing and re-mixing going on here: A contemporary black actor (Ryan Woods) portrays a black playwright – BJJ, Jacobs-Jenkins’ stand-in – who decides to put on a favorite old stage drama, ‘The Octoroon,’ and ‘white faces’ himself up in order to play both of the leading roles, the hero and villain. The 1859 melodrama by Irish playwright and producer Dion Boucicault (pronounced ‘BOO-see-KOH’) is set on a Louisiana plantation, where the fates of the black slaves and white slave owners are tied to a missing letter. What’s more, a mixed-race woman (Morgana Wilborn), who is one-eighth black – the ‘octoroon’ of the title – is in love with the white plantation owner who cannot marry her. She’s a trapped, Victorian heroine and victim – she might as well be tied to the train tracks of her destiny (a theatrical cliche, by the way, that Boucicault created).

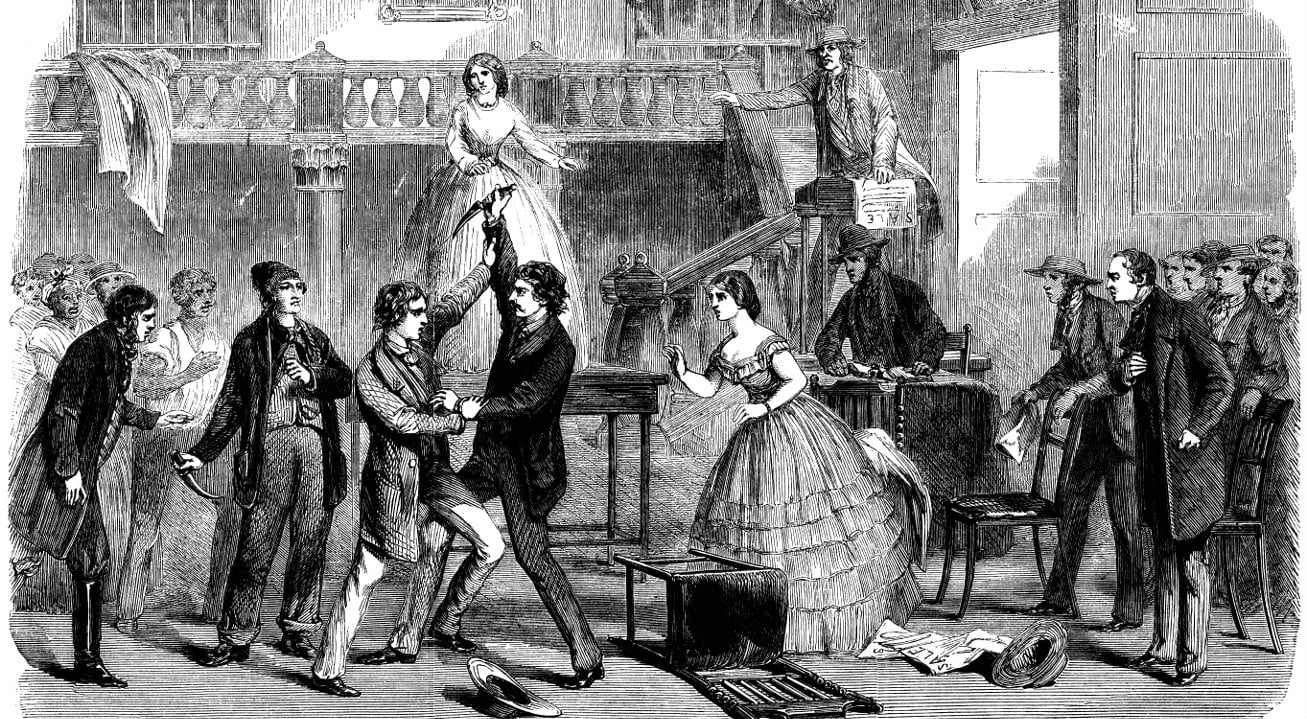

The climactic fight scene from ‘The Octoroon’ as staged at the Adelphi Theatre. Image: UMass Edu Adelphi Project.

Racial-and-facial identities flip back and forth here like playing cards in an old magic trick. BJJ’s therapist suggested he stage this project so he could work out his feelings about whites, and the playwright even has his counterpart playwright, the imperious Boucicault himself, appear onstage (Justin Duncan) – complete with comic Irish accent – to defend his inventive dramatics and to play a ridiculous, drunk, ‘red’ Indian in the play.

The ‘performance’ of race means next to nothing here; it’s all hokey theater. The black face, white face and red face characters are created mostly with a crude smear of color and some cartoonish voices, minstrel shuffling and a white wig that looks like a flattened Persian cat. They are all just joke gestures or cringeworthy conventions.

Except that race also means everything here when it comes to power: who has it, who gets sold, who profits, who can marry whom, whose story gets told on stage – and who will do the telling? One of Jacobs-Jenkins’ repeated jokes is that the production has been pruned and altered because they couldn’t get enough white actors for the roles. Typical. It’s an ironic inversion of the white artistic director’s tired complaint heard so often: There aren’t enough African-American performers around to program anything more than the single black play he has in his season.

In interviews, Jacobs-Jenkins has said that, contrary to contemporary artistic preferences, he actually likes contrived stage melodramas like ‘The Octoroon.’ This one happens to include a burning ship, escapes, a murder and a brawl at a climactic slave auction. Melodramas – like paperback thrillers and reality TV shows – foreground our fears and values about money, power and sex without clarifying them. They’re simply on display, loud and proud and sold to us all over again. Whatever conflicts there may be, they’re not resolved, they just get neatly tied up by plot mechanics – in this case, via that newfangled device, the camera – to assuage (or inflame) our sympathies.

And in 1859 America, arguments about race were never so inflamed: A half-million of us were about to get slaughtered over what it meant to be black or white and the system that had enslaved several million on one side of that color line. At this precise moment, Boucicault dared to defy racial taboos with his sympathetic, mixed-race Zoe (a character type who came to be known as the ‘tragic mulatto’ – still alive and well in American theater in 1981 in Charles Fuller’s ‘A Soldier’s Play’).

Ryan Woods, Christopher Llewyn Ramirez and Jordan Duncan in ‘An Octoroon.’ All photos: Evan Michael Woods

Actually, the opportunistic Boucicault simply ended up cashing in by managing to satisfy both abolitionists and secessionists. Segregation was even reinforced: The tremendous success of his play helped popularize the term ‘octoroon’ as well as the ‘one drop’ rule (one ‘drop’ of black blood made a person ‘fully’ African-American – a rule featured 37 years later in Plessy vs. Ferguson, the Supreme Court decision that mandated ‘separate but equal’ facilities for blacks and whites: Homer Plessy was an octoroon classified as black who challenged racial separation in Louisiana).

What Jacobs-Jenkins does with all this – in director Akin Babatunde’s capable hands at Stage West – is deconstruct it with flair, when he’s not hilarious or shameless about using racist and sexist caricatures: We’ve got stereotypes inside stereotypes here. The results are far more scathing, smart and funny than the Dallas Theater Center’s similar but disastrous effort two years ago with the world-premiere musical, ‘Bella‘ – partly because Jacobs-Jenkins implicates himself in the proceedings.

We open on a conventionally spartan, contemporary setting: a dark, empty stage with a ‘ghost light’ (the light that’s left on in darkened theaters) and the rope riggings dangling down that are used to haul up the painted scenery of an old-fashioned theater (and which will also evoke nooses). Bob Lavalee’s set exposes the mechanisms of the Victorian stage, just as the play will: BJJ promptly comes out to explain what drove him to try to revive such a period drama and what it took to get it staged. Then up go the canvas back drops and out comes the meta-theatrical minstrel show.

Much of the humor in ‘An Octoroon’ resides in just this exposure of the creaky period theatrics and racism. This bi-polar consciousness – we’re in both the 19th and 21st centuries, long ago and very much today – is embodied, for example, in two female slaves, Dido and Minnie. Dido (Bretteney Beverly) is the traditional ‘mammy’ character – deferential, concerned, maternal – while Minnie (Kristen White) is the sassy, young black female cliche of today’s TV shows and films: the sardonic best friend, the ‘mouthy’ employee, the drunken date. Together, the two are almost a Greek chorus, fretting and gossiping about what’s going on.

And now, let’s take a moment for a personal aside. If Jacobs-Jenkins can enter his own play, I’ll step forward briefly into this review. My wife’s grandmother, Berneice, passed away a few years ago in her nineties. When she was young, Berneice toured Texas in a stage company in the 1920s. And in these shows, she often played the maid.

In black face.

Berneice ‘corked up’ (put on burned cork to paint her skin dark), donned a wig and played the comic black maid, a character much like Minnie, the wisecracking, all-knowing servant, a role that’s as old as the commedia. I’m embarrassed to say I was a little staggered to hear all this, not so much for the racism involved, but for my proximity to it. Now I was directly related to someone, a sweet woman whose hand I’d held while she lay in bed in her assisted living center, a woman who had played a ‘stage darkie.’

Nikki Cloer, Morgana Wilborn and Ryan Woods in ‘An Octoroon.’

In other words, the American minstrel show is not so far from us. All the ridiculous, racist trappings we laugh at in ‘An Octoroon’ – your parents or grandparents could have accepted and enjoyed. Boucicault’s play was last staged on Broadway in 1961. It was favorably reviewed. A chief reason BJJ wants to stage it is that we’re still trapped in it today – our cartoons are just hipper, more jaded. Mocking Boucicault’s dated efforts is easy enough, but BJJ aims to undermine his play, defang its power, escape the box we still put him in: the ‘black playwright.’

As BJJ, Bryan Woods is little short of heroic in a physically demanding performance that has him playing three different characters, at one point pretty much all at once: the sardonic, seen-it-all modern playwright, the noble plantation owner and the Snidely Whiplash-like villain. Kristen White is as delightfully energetic and smart-talking as one would hope playing Minnie, while Morgana Wilborn couldn’t be more demure as Zoe. The only weakness in ‘An Octoroon’ is that Jordan-Jenkins knows too much, is too post-modern smart for his own good: He even brings in Br’er Rabbit (Christopher Lew). He looks like Alice’s White Rabbit has hopped into the wrong play, when he’s actually another historic quotation. He seems to serve no function except to emphasize the surrealist, mythical quality of the proceedings – and to display an African-American folk tradition popularized by a white author, Joel Chandler Harris.

And then (spoiler alert), it all ends too abruptly.

That’s disappointing insofar as one wishes to hear more from a character as sharp and self-aware as BJJ , especially now that he’s undergone his therapeutic experiment, and at Stage West, it’s led to such satisfyingly outlandish, deconstructed results. But for Jordan-Jenkins, what other ending or additional explanation could he supply? What other resolution could we realistically expect? After all, he revised Boucicault’s original title from ‘The Octoroon’ to ‘An Octoroon.’

Meaning, of course, this isn’t over. There will be others.