Review: ‘As We Lie Still’ At Contemporary Theatre

ArtandSeek.net November 15, 2016 49There’s an infamous magic trick known as the ‘bullet catch.’ Basically, a person equipped with a fully functioning firearm blasts away at the performer. But, as the illusion’s name implies, the performer magically ‘catches’ or stops the bullet instead of, you know, gaining a large bloody hole in himself. The bullet catch is infamous because since the 17th century, several magicians (and assistants and family members) have truly died doing it — the best known being the ‘Chinese’ magician Chung Ling Soo (real name: William Ellsworth Robinson), who was shot to death onstage in 1918.

Dallas composer-lyricist Patrick Emile and his wife and bookwriter Olivia de Guzman Emile have been developing a new musical, ‘As We Lie Still,’ around the idea of taking such a shooting death one logical step further: What if the victim could then actually, magically, be revived? And what if they could do it again and again, show after show? Repeatedly topping Jesus’ big solo finale would certainly qualify as a box-office draw. The entire idea has a sense of bravura and historical fascination to it — akin to Christopher Priest’s 2005 novel, ‘The Prestige’ (and the Hugh Jackman-Christian Bale film adaptation), which is based on a related premise, cheating a different kind of “death-defying” illusion (both novel and film, in fact, reference Chung Ling Soo).

Level Red Spoiler Alert: Some readers may feel the summary that follows reveals too much.

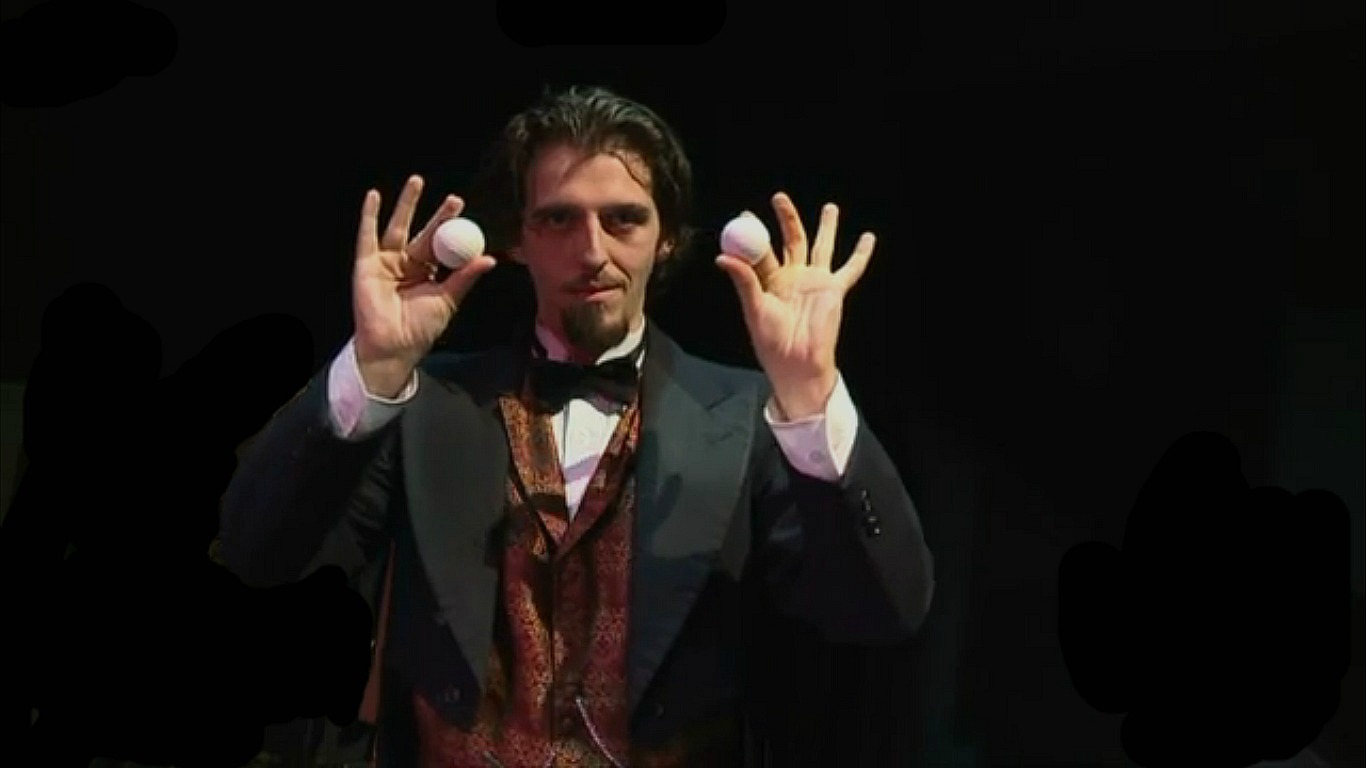

Wyn Delano as the Great Marduk in ‘As We Lie Still.’

In ‘As We Lie Still,’ the turn-of-the-century conjurer in question — the Great Marduk or Avi Leiter (played as your typical imperious, young fame-seeker by Wyn Delano) — has rummaged through ancient books of ‘real magic’ in pursuit of an illusion that will catapult him to stardom. He finds an incantation that supposedly can resurrect the recently deceased. Not surprisingly, his likable, loyal, somewhat dim backstage assistant, Billy (Jovane Caamano), is neither so loyal nor so dim as to get himself shot just so his employer can prove he’s able to abracadabra back from the afterlife. But then Leiter hires a smart, attractive, onstage female assistant, Josephine (Ms. Emile) — and things go disastrously wrong.

Understandably, much of the press attention given ‘As We Lie Still’ has been directed at the undeniable technical feat of making a musical credible as a conjuring act. Fortunately, ‘As We Lie Still’ is set more than 100 years ago, which means the talented magic consultant Trigg Watson must replicate only fairly traditional, seance-and-stage illusions from the period: the linking rings, card tricks, the levitating girl. The tricks are pleasantly handled (I enjoyed the playing cards geysering from a top hat), and they’re astutely augmented by the entire atmosphere of hocus-pocus that technical director Robin Binford has built into the set.

But it’s Peter Rand’s handsome video projections that may be the single most effective aspect of the production design: They let us know where and when we are with evocative, tintype period detail, while also adding ethereal, visual interest to an otherwise simple-looking black stage. Kudos as well to the gifted director Michael Serrecchia for juggling what is easily Contemporary Theatre of Dallas’ most ambitious production to date — including a 12-member cast.

For his novel, ‘The Prestige’ to work, author Priest had to come up with an electrical gizmo, courtesy of the inventor Nikola Tesla. Tesla’s device permits the magician to replicate himself, and thus have new ‘versions’ of himself die night after night. But in ‘As We Lie Still,’ in order for the premise of Leiter’s grand illusion, ‘The Resurrection’ to succeed, we need an after-life. Inevitably, that would be one of the first questions anyone would ask following an onstage revival, other than whether this is covered by medical insurance. Where did Josephine ‘go’ while she was dead? What’d she see? Long tunnel or pearly gates?

Look into my eyes: Jovane Caamano, Olivia de Guzman Emile and Wyn Delano in ‘As We Lie Still’

Look into my eyes: Jovane Caamano, Olivia de Guzman Emile and Wyn Delano in ‘As We Lie Still’

But establishing a credible after-life is a different order of theatrical challenge than showing us some sleight-of-hand. No amount of stage fog will necessarily make St. Peter or Shiva a real character. Which is perhaps why an onstage hereafter seems rarer than a musical-with-magic: I don’t know of many Broadway shows that actually ‘go beyond the grave’ and bring the audience there — except perhaps “Cats,” which hardly qualifies because only Grizabella ascends to the ‘Heavyside Layer.” There’s also Bruce Jay Friedman’s unfortunately neglected dark comedy, ‘Steambath,’ in which God is a Puerto Rican sauna attendant, and the classic, black movie-musical, ‘Cabin in the Sky’ from 1943. Otherwise, I believe, agnosticism pervades. There certainly have been musicals and comedies populated by the occasional spirit — like ‘Ghost’ — but they appear only here on Earth. Heaven primarily seems to exist offstage.

So faced with the prospect of creating the hereafter, the Emiles, director Serrecchia and costumer Michael Robinson (who also portrays the older Avi) have gone somewhat New Agey-ancient Egyptian. We meet Azriel (Aaron Green), who is often popularly identified as the ‘Angel of Death’ or ‘Angel of Transition.’ Here, he’s more the ‘Angelic Hall Monitor’: He keeps the befuddled souls of the recently departed headed in the right direction. But because the now-she’s-dead, now-she-isn’t Josephine keeps jumping the queue, he’s intrigued by her — and theirs becomes something of a reverse Orpheus-and-Eurydice story.

It should be clear by now that while I recognize the necessity of the after-life in ‘As We Lie Still,’ I accept it provisionally — only as a plot device. I suspect most theatergoers feel the same: Let’s see where they’re going with this before we commit to it. Unfortunately, that leaves Azriel and his emotional needs feel disembodied. And that undercuts a large portion of what happens.

In fact, motivation is a problem throughout the show. The way the storyline has been outlined above is not the way the audience encounters it. Instead, we begin, more or less, with the older Avi, now reduced to fussing around his dusty bookshop of arcana and holding the occasional seance for pocket money. One day, in rushes the young Ruth (Monique Abry) who has somehow learned of Avi’s scandalous, ‘revivalist’ background, She pleads for him to give it a go one more time for her husband Michael (Kyle Montgomery) who’s in a coma. Avi refuses — all that old stage business that he once did only ended up in heartbreak.

And right there is where the problem starts. Broadway musicals typically follow the convention known as the ‘I Want’ song. It’s when a character, overcome with emotion, spells out precisely what he or she needs or hopes for, and that emotion powers them forward (and possibly powers the entire show). A character can even have several “I Want” numbers as events and characters change (Jean Valjean basically has a whole slew of them in ‘Les Miz’).

The after-life as a dance number: Olivia de Guzman Emile, Aaron Green and Ashlee L’Oreal Davis in ‘As We Lie Still

We know what Ruth wants: her beloved back on his feet. She sings about her longing and her fears of losing him. And we sort of know what Avi wants. We don’t know the whole resurrection story yet, but it’s clear he both misses his old stage glory and regrets the way everything turned out.

But Avi turns Ruth down. Sorry, no coming-back-t0-life. Not going to happen.

So what happens? He lets her work around the shop. And they happily go get some ice cream in Central Park, and enjoy Billy’s company, yada yada. But why? If there’s a quick justification for all this I confess I missed it. But even if there is, it had better be a good one because Michael’s still lying on his deathbed and Avi’s still not helping. Why wouldn’t Ruth resent Avi, why isn’t she off desperately dialing different medical specialists and why hasn’t Avi — unpleasantly reminded of his past failures — shut the door on her?

Husband Michael, by the way — the subject of all this anxiety — remains almost as immaterial as Azriel. We see him once in a meet-cute flashback with Ruth — and that’s it. (He’s a little like Josephine’s child, whom we learn of almost in passing as her motivation for seeking a stage job and isn’t eally brought up again.) So we never see Ruth visit Michael’s bedside, which might impress a sense of urgency on things. Instead, she wrings her hands once or twice and then goes off to learn the fake-seance con with Avi.

This fuzziness over the main character’s motives isn’t immediately apparent because ‘As We Lie Still’ doesn’t unfold chronologically. It intertwines the past, the present and the after-life in flashbacks and flashforwards and flashes upstairs (hence, the welcome service of Rand’s video projections). Basically, for much of the show, we’re distracted by learning the intricacies of Avi’s backstory and the way the next world functions like the DMV.

Then, all caught up, we see Ruth rush in again, tell Avi of another (somewhat foreseeable plot development) and Avi immediately works to crank up the old incantation. This would imply that, without this new development, Avi would have been perfectly content to leave Michael in a coma, while he and Ruth puttered around the shop.

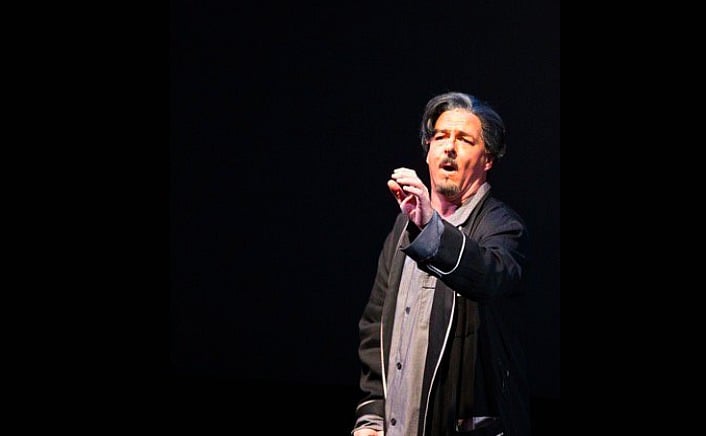

Michael Robinson as the older Avi in the New York Musical Theater Festival production of ‘As We Lie Still.’

I’ve gone into the book problems in ‘As We Lie Still’ in such detail because book problems are notoriously what kill many musicals. And judging from the reviews when ‘As We Lie Still’ debuted at the New York Musical Theatre Festival, the show’s creators sense some of this as well. They’ve tinkered with the show’s opening (it was originally a hospital bedside scene, interestingly enough) and the way the story unfolds.

But what’s also clear is why they’d persist in re-working ‘As We Lie Still’: The entire show has a strong, appealing Sondheimian flavor — in its complexity, its self-consciously theatrical setting, its ingenious interlocking themes of life-and-death, real-or-fake and its overall subjects of loss, memory and regret (think of ‘A Little Night Music’ or ‘Follies’ or even ‘Into the Woods’). Guzman’s often attractive music is also Sondheimian in the way he frequently turns dialogue into seemingly scattered musical lines that then fuse into a whole song. Less successfully, he uses a prologue to introduce the show and the characters (shades of ‘Night Music’ and ‘Into the Woods’) but doesn’t succeed very well. As the show properly gets underway, we still really don’t know who all these people are who’ve been milling about the stage.

One reason we don’t is that Emile is not as deft a lyricist as he is a composer. With Sondheim, even when his music (and the scene in general) functions as exposition, Sondheim holds our interest with wordplay, with chit-chat condensed into poetry, with vivid lines that reveal character in a flash and a phrase. Emile has several passages that ring out, and he knows it because they’re repeated to great effect: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, what you are about to see is real magic!” And “real as a rainbow and right before your eyes!”

A comic interlude — Billy’s “Life of a Stagehand” number — is welcome precisely because it evokes his likable character, what he does and how he goes about doing it. It’s a perfect little cameo, but it’s pretty well unconnected to the narrative around it. It seems to exist mostly to provide a light-hearted finish to the first act.

That’s not a bad reason for a number to exist. In fact, the show needs more of that functional clarity. It will be real magic — and welcome magic as well — if the creators of ‘As We Lie Still’ can ultimately pull this rabbit out of the hat.