Review: Echo Theatre’s World Premiere Of ‘Temple Spirit’

ArtandSeek.net April 10, 2016 24Japanese folk tales (monogatari) frequently have a spareness to them, as if they’ve been rubbed smooth by many hands over the years. The plot can twist and turn, and strange ogres may certainly appear, but the psychology of the characters is kept to a mininum. They’re tagged the ‘wise poet’ or the ‘greedy monkey,’ little more. Their nature may change or their true motives may be revealed by the end, but that’s determined by events, not inner drives.

In short, we are presented with an apparently simple landscape of moral outlines and symbolic actions, where fire demons and ghosts are taken for granted. Hence, the stories’ dream-like, portentous quality. And all of this is conveyed in a prose that’s unadorned (judging from some translations, at any rate — best to avoid the fancied-up, late Victorian ones).

Given its premiere by Echo Theatre, Susan Felder’s ‘Temple Spirit’ is inspired by such Japanese tales. Felder has tinkered with a couple of classics as well as the great historical legend of Chushingura or the Forty-Seven Ronin.

Yet in ‘Temple Spirit,’ the landscape we encounter is one of muddle and needless elaboration, of overwritten prose and over-produced artifice.

It’s frustrating. Given the amount of talent and effort involved in the show, one wishes it were better. Echo Theatre has not merely staged the play, the company has gone to the trouble of finding and refurbishing an old, out-of-the-way performance space — the Show Place Theatre in the Creative Arts Building in Fair Park. During the State Fair, it’s a home for puppet shows — amid the quilts and cooking demos. Interestingly, it’s also a traditional proscenium stage. These are rare in North Texas, once we get past the big touring houses like the Music Hall at Fair Park.

‘Temple Spirit’ is also staged by Jeffrey Schmidt, one of our busiest, more resourceful designer-directors — it was he who brought the play about a haunted temple to Echo’s attention. The temple set design (by Schmidt), the gloomy lighting (Robert McVay) and the costumes (Melissa Perkins) — together, these represent one of the more sophisticated productions from Echo I’ve seen. But there are also masks, shadow puppets, silk-rope dancing, bamboo flute music, the whole grab-bag of Oriental paraphernalia.

The aim is an atmosphere of far-away wonder and artful spookiness. But the production elements often seem unnecessary or distracting — so much decoration. The shadow puppets, for instance, are used mostly for literal-minded illustration. When a crane is mentioned, we promptly see a shadow puppet of a crane. So that‘s what the birds look like. Whatever evocative Japonisme this might add (cue the bamboo flutes), it does little, really, to advance or deepen the story.

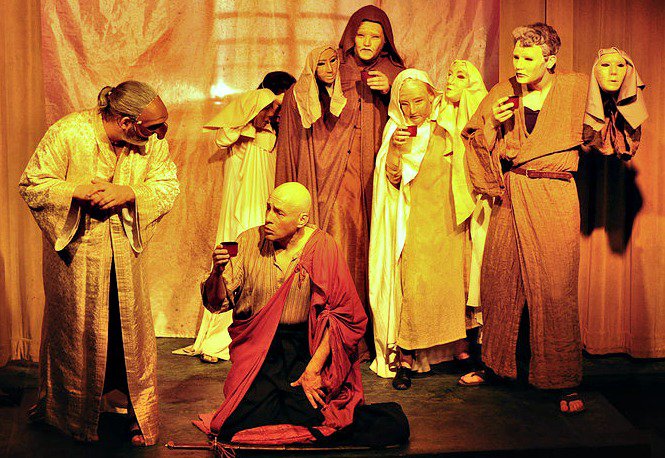

Echo Theatre’s ‘Temple Spirit’: The traveling priest (Anthony Ramirez, kneeling) first meets the unhelpful townsfolk.

Simpler would have been better, even a stark, dark simplicity. That’s because it might counter Felder’s script, which abandons the straight-ahead narrative of a traditional folk tale for a roundelay of stories-within-stories. The basic set-up is borrowed from the 18th-century tale, ‘A Haunted Temple in Inaba Province.‘ A samurai-turned-priest (Anthony Ramirez, getting a heroic workout) is determined to spend the night in a mountain temple infested by demons. The local villagers won’t help him — others who’ve tried before have died, so why bother? — even though, spiritually, the wretched village could use both temple and priest. During his vigil, the priest must endure not only the demons’ assaults but their life stories. Eventually, it becomes clear that redeeming and restoring the old temple will require his own redemption as well. (One can’t help but think of Echo restoring the Show Place Theatre.)

The tales the demons tell start off well enough with a fisherman (Alexander Ferguson) and a ‘flute girl’ (Lorena Davey) relating a variation of ‘Tsuru no ongaeshi’ (‘The Grateful Crane’). Davey’s mournful voice goes far in conveying the story’s theme of love as unrequited self-sacrifice.

But by the end of the evening, after the priest has heard the tale of the Firefly Queen (Nicole Berastequi) and that of a young female banshee trapped in a well (Danielle Pickard), just what the priest should take away from all the intertwined layers of frustration, betrayal and failure is not clear. Perhaps they’re intended as a collective portrait of human unhappiness, a kind of recruitment pitch by the demons. Look upon these and despair — as we did. In which case, two or three of the stories could be chucked; despair would still be felt, but confusion would be less of a factor.

One example must suffice to indicate the puzzlements encountered in Felder’s writing. At one of the play’s small and long-awaited moments of suspense, our priest has a knife held to his throat; his violent death is imminent. That’s what the gloating demon Nezumi promises (in Ian Ferguson’s impressive, Kelsey Grammar-ish tones). But the good priest replies, no, I defeated you, I showed mercy, I spared your life. So you owe me a life.

Freeze. The two characters now hold their positions, the knife remains where it is. And they repeat this same exchange (you’re going to die – no, I was merciful) through four or five elaborate variations. Why? The tension is not heightened, nothing is added, nothing is clarified. To make things happier but even less clear: By my count, Nezumi actually spares two of the characters. Which would seem to mean the priest eventually owes him a life.

Ramirez has most often been a comic character actor employing his booming voice, expressive face and boundless energy. Playing an action-hero priest is a welcome stretch, made all the more credible by the fact that his bald dome makes Ramirez — from some angles — resemble a younger Bruce Willis. Yippie-kay-ay. In Felder’s fashion, the whole question of whether the priest is actually a cowardly survivor of the famous ronin is brought up, used to taunt him and then more or less abandoned. Ramirez doesn’t have much opportunity to explore the character of a tough, veteran warrior-turned-gentle priest haunted by his past failure to live up to a strict code of action (in movie terms, he’s the mysterious, troubled stranger who comes to town and ultimately sets things right). Too bad. In wrestling with whether he is truly a priest or a samurai, Ramirez is more affable — especially in his interactions with a helpful young lad (Brittney Dubose) — than he is tormented.

Just what ‘Temple Spirit’ intends to be is equally unsettled. At the end, the priest sums up what he’s learned by saying, to truly understand the light, one must sit in the darkness. Is that it? And is such an easy morale even necessary? As folk tale wisdom goes, it feels a bit canned considering everything the priest has endured, all the sad, fantastic stories he’s heard.

It seems that when ‘Temple Spirit’ does, at last, aim for the simple and direct, it hits the simplistic.