Review: ‘Inherit The Wind’ At The Dallas Theater Center

ArtandSeek.net June 6, 2017 35It may be hard to believe but Larry McMurtry actually wrote ‘Lonesome Dove’ to savage the traditional Western. He tossed in random cruelties, prostitutes, diseases, meteorological catastrophes, murderous madmen and dull-witted cattle – in short, many of the unpleasant elements Hollywood Westerns have often left off-screen. To McMurtry’s puzzlement, even embarrassment, his dark satire was welcomed as a sweeping saga of the grand old sort, a ‘Gone With the Wind of the West,’ as he put it.

McMurtry threw as much mud at the myth as he could, and director John Ford was still right: ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’

And so it is with ‘the Monkey Trial.’ The Dallas Theater Center is both promoting and staging a revival of the classic 1955 courtroom drama ‘Inherit the Wind’ in ways that say one thing, while the director and authors believe the play says another. In advance interviews, DTC artistic director Kevin Moriarty has argued, quite accurately, that playwrights Jerome Lawrence and Robert Lee declare in their introduction to the printed version of the play that it was not written as history. It’s not a lightly revised version of the 1925 court case in Dayton, Tennessee, when former presidential candidate-turned-popular-evangelist William Jennings Bryan helped prosecute John Scopes for teaching evolution in a public school – against the defense led by the outspokenly liberal attorney Clarence Darrow.

The play was certainly inspired by these events, occasionally draws on them (though it rarely uses actual court testimony). But Lawrence and Lee basically meant they didn’t write ‘Inherit the Wind’ to re-hash the trial’s 30-year-old faith vs. science exchange – and certainly not as a museum display of outmoded thinking. Moriarty has said that reading their intro caused him to view the play with fresh eyes. His production would daringly reinterpret the play by simplifying it, shedding the script of both its period details and its traditional treatments (notably the 1960 Spencer Tracy film). By presenting it without all those distancing distractions, the play would be seen as immediately relevant to our lives, our time.

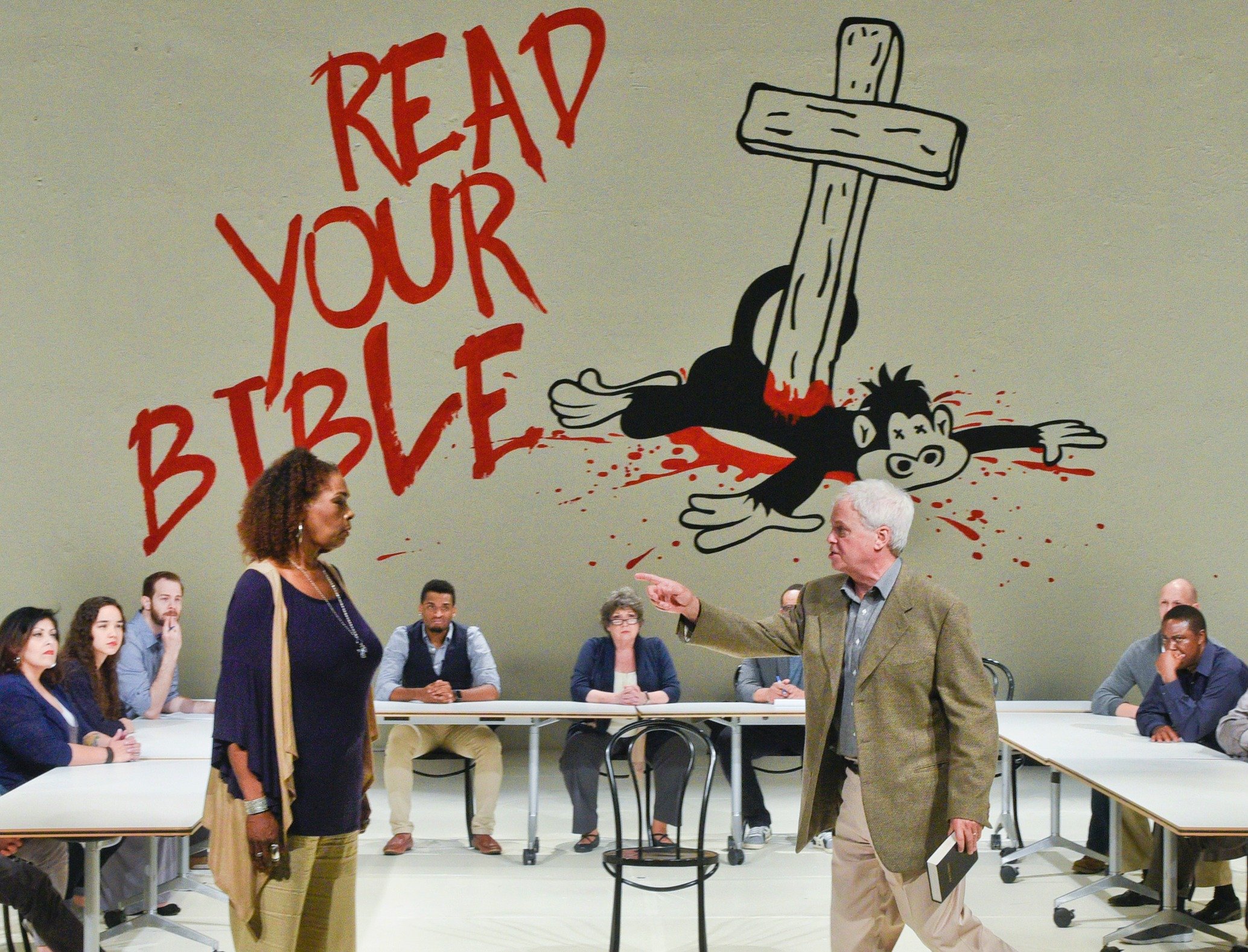

Liz Mikel as Matthew Brady and Keiran Connolly as Henry Drummond face off in court in the Dallas Theater Center’s ‘Inherit the Wind.’ All photos: Karen Almond

In the ’50s, Lawrence and Lee were actually more concerned about the rise of American anti-intellectualism and the threat of a bullying, paranoid, right-wing populism. In this light, ‘Inherit the Wind’ should be classed as another metaphoric treatment of McCarthyism – alongside ‘The Crucible’ and ‘High Noon’: The independent-minded stalwart makes his lonely stand against the angry and fearful majority. So the drama was not really intended to be what it’s often seen as – a rallying cry against the (re)introduction of Christian ‘creationism’ into American science classrooms. Edward Larson’s superb history, ‘Summer for the Gods‘ – which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1998 – details all this.

But as McMurty learned with ‘Lonesome Dove,’ what an artist intends is not necessarily what his audience sees. After all of Moriarty’s statements – and Lawrence and Lee’s original declarations – the DTC production is a thoroughly convincing indictment of Biblical literalism, which, of course, in the form of ‘intelligent design’ remains a persistent controversy in the selection of Texas schoolbooks.

In other words, it’s difficult to see this revival of ‘Wind’ as particularly ‘fresh’ other than in its ultra-spartan production values or as particularly anti-McCarthyite. The DTC promotes it precisely as a re-match of faith vs. science. It’s hard to imagine anyone seeing the ads and programs – with a monkey clutching a cross and the question, ‘When Religion and Science Collide, Who Wins?” – and think of the play any other way.

But perhaps that’s just the theater’s marketing department angling for public interest: Selling conflict sells tickets, especially when we’re talking about riled-up religion and politics. Yet Moriarty’s staging sends the same message. The nakedly simple set – so naked that no set designer is credited – has a back wall emblazoned with a large caricature of a chimp impaled by a bloody crucifix and the command, ‘Read Your Bible.’

Nope, doesn’t look like anti-McCarthyism is on the menu this evening. We’ll be getting re-heated Darwin vs. God.

And Moriarty’s opening only confirms this. He’s added a prologue in which actors recall early encounters with Biblical literalism or their first doubts about such literalism. This certainly brings faith vs. religion up to the present day, but this means the production may not be ‘history’ (as in dated-looking) but it’s director’s own device sets up the same, Spokes-era conflict of faith and reason.

Moriarty has used such unnecessary preludes before, and their purpose seems to be to make the actors more like us in the seats (as if they weren’t already). But having self-consciously revealed some detail from their ‘real’ lives, the actors immediately step back and become actors, they shift into different characters. So the prologue actually draws attention to their function as performers. At the same time, their stories introduce a fake-folksy didacticism that ‘Inherit the Wind’ already suffers from. Essentially, the prologue says, “The issues we’re about to debate are still relevant and timely today. They’ve even impinged on my life offstage.” Yet relevance is something a play enacts; it’s not something a performer asserts.

As for the rest of Moriarty’s staging, some theatergoers are not able to see past its gender-and-racial-neutral casting: A black actress (Liz Mikel), for instance, portrays Matthew Harrison Brady (the play’s stand-in for William Jennings Bryan), while a black actor (Akin Babatunde) portrays his wife. Such non-traditional casting has practically been the DTC’s stock in trade. ‘In the Beginning’ had a biracial Adam and Eve way back in 2009. Sally Nystuen Vahle recently portrayed Ebenezer Scrooge. For those who object to such casting, one might wonder what shows they’ve seen at the DTC.

Hello, cousin: Alex Organ as the sarcastic journalist E. K. Hornbeck in the Dallas Theater Center’s revival of ‘Inherit the Wind.’

What’s surprising about Moriarty’s bare-bones approach is that it honestly becomes effective, even as much of it initially feels contrived. It strips the play down to its strength: the courtroom cross-examination. The staging is so bare one suspects cost-savings inspired it as much as any dramatic vision. (Recall all those audience headsets in the recent revival of ‘Electra’ or the giant cast required for the community-participation ‘Tempest’ the DTC just staged – those productions were expensive.)

The approach is so plain, it’s plain-spoken. The actors don’t speak in dialects or accents. That’s a hurdle for many in the cast because they portray multiple characters. Some of the townfolk are talkin’ and droppin’ their g’s, and darn it, some of ’em don’t, yet everyone sounds alike. No one has a discernible Tennessee twang or in the case of E. K. Hornbeck (based on the bilious journalist H. L. Mencken) no Baltimorese.

So the actors have no historical props or costumes or wigs, no set, no distinguishing voices or accents. They do have that large, blood-red banner and dead chimp – a Brechtian splash, perhaps, amid all this spare modernism. Otherwise, they are left with just bare words and bare emotions.

Which, as noted earlier, is more than enough when it comes to the famous back-and-forth court argument between Bryan’s righteous but blinkered Christian faith and the snapping skepticism of Drummond (the play’s stand-in for Clarence Darrow). Some of Drummond’s arguments (much like Darrow’s in real life) are of the village atheist variety. If God is all-powerful, can he create a mountain that he can’t climb? Who was Cain’s wife? That kind of thing.

Yet this exchange still grips and entertains because Moriarty was right about casting Liz Mikel. She’s a larger-than-life performer bringing the kind of larger-than-life presence that Brady needs – without making him a blowhard or a fool. As Drummond, Kieran Connolly has a wary, gimlet-eyed quality; he’s a scarred old brawler who, like many aging boxers, has had some human sympathy pounded into him. And in the role of Hornbeck, the play’s annoying and self-admiring wit, Alex Organ excels, once again, as a gleeful, jeering cynic.

It’s too bad that Lawrence and Lee fall into one of the things they treat with mild scorn: preachiness. “An idea is a greater monument than a cathedral.” If ‘Inherit the Wind’ has any truly famous, lasting quotation, it’s that one, one of Drummond’s comebacks. It’s a glib pseudo-profoundity. Chartres Cathedral, York Minster, La Sagrada Familia, Hagia Sophia: These cathedrals can awe a viewer with their aspirations and the abilities of the hundreds of artisans who carved and painted and built them over decades. The architecture, the lighting, the sheer scale of these structures can crack open a mind, flood a person with appreciation for what our fellow hominids are capable of – out of simple faith or brilliant engineering.

Meanwhile, there are plenty of dumb ideas, ideas we learn only later were stupid or self-defeating. In real life, one of the wisest reasons Bryan had for opposing the theory of evolution was that it offered the cold-hearted rich a ‘survival of the fittest’ justification for leaving the poor to their suffering. It’s their own fault; it can’t be helped. Bryan was correct. Darwin’s theory led, mistakenly but eventually, to social Darwinism which led to eugenics which led to the Holocaust. And one can still hear ‘law of the jungle’ justifications behind some proponents of free-market economics – as if hedge-fund trading was a form of ‘natural selection.’

Akin Babatunde and Liz Mikel as Mrs. Sarah Brady and Matthew Harrison Brady in ‘Inherit the Wind.’

In fact, the late, great paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote that the average American, if he knows anything of the ‘Scopes monkey trial,’ knows three things: High school teacher John Scopes was persecuted for teaching Darwin, Clarence Darrow made a fool out of the Bible-thumping William Jennings Bryan in court and the entire case was a victory for freedom of thought. It kicked fundamentalism into retreat, prompting its long, declining influence on American thought and politics.

All three ideas, Gould pointed out, are wrong. As the DTC program for ‘Inherit the Wind’ notes, the facts are that Scopes willingly enlisted in the ACLU’s campaign to challenge the Tennessee law banning evolution. Dayton courted the entire controversy for the tourist trade, Scopes lost and was fined and at the time, much of America did not see the case as a titanic struggle over the country’s soul. It was another summer carnival, a traditional bit of American hokum and hot air. It was only Bryan’s death five days later that, in hindsight, lent the case epic significance. As for fundamentalism’s decline, in the years immediately following the trial, some 41 anti-evolution bills were introduced in state legislatures across the country.

Much of the reason any of us remember the Scopes trial – remember it incorrectly like this – is ‘Inherit the Wind.’ That’s not to say the play is a bad play, that its effects have been entirely misleading. It’s just that it doesn’t do what Lawrence and Lee thought it would. It’s rarely – if ever – been taken as a warning against McCarthyite demagoguery. For good reason, that’s not really what the play argues. But neither do people often recall its ending, in which the playwrights try to soften their sometimes simplistic depiction of Biblical literalists in the person of Brady, portraying them as motivated primarily by the fear of modern science. Actually, William Jennings Bryan had been a determined trust-buster and anti-imperialist, the leader of the progressive wing of the Democratic party for 20 years.

But print the facts and we’ll still remember the legend.