Review: ‘Romeo and Juliet’ At The Dallas Theater Center

ArtandSeek.net February 19, 2016 57

All the other kids with their pumped-up kicks: Robert George as Tybalt vs. Drew Foster’s Mercutio at the Dallas Theater Center.

Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo & Juliet’ has often been used by theaters to attract younger audiences – because of its story of the tragic love between two teenagers. The Dallas Theater Center’s current production follows that pattern – the play has been stripped down and made contemporary with torn jeans, pop music and gunplay. KERA’s Jerome Weeks sat down with Justin Martin to sort out whether this approach really works or not.

Justin: When it comes to the Shakespeare plays, Dallas Theater Center artistic director Kevin Moriarty wants to make them accessible to teen audiences by simplifying the language and making things look contemporary. But as admirable as that intention may be, you’ve described the results as often approaching ‘short-attention-span Shakespeare.’ Is that true with the current ‘Romeo and Juliet’?

Now, by far, the best known example of this kind of ‘kid-accessible’ or YA approach has been film director Baz Luhrmann’s deliriously over-the-top movie version, the one starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

You remember it? Lemme guess. You hated it.

I hated it.

Like an hommage?

In the film, for example, Romeo hangs out in a pool hall with his buddies. Onstage here, same thing, a pool hall. In the film, the young lovers sneak away to get secretly married by Friar Laurence, and his church has these rows of big, white, neon crosses. Same thing here – although it’s just one big, white, neon cross with neon stripes overheard. There are maybe a half-dozen of these ‘visual echoes,’ some less obvious than others.

Dash Mihok as Benvolio shooting some pool with Leonardo DiCaprio as Romeo in Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’ (1996)

Such as?

Sometime she driveth o’er a soldier’s neck,

And then dreams he of cutting foreign throats,

Of breaches, ambushes, Spanish blades,

Of healths five-fathom deep; and then anon

Drums in his ear.

So what’s the overall effect of these ‘quotations,’ as you call them?

To be fair, in his film adaptation, Luhrmann is aiming for the trash-operatic, the chic and grandiose. That’s not Ferrell’s game. He does more than just quote Luhrmann here. He’s got some theatrical inventiveness going on to keep his adolescent audience members awake and engaged. He boldly opens the play with the ominous, final death scene. A morgue full of white-shrouded corpses strikes a death-haunted note more effectively than the traditional prologue usually does (“the fearful passage of their death-mark’d love”). Ferrell also pulls a smart bit of cross-gender casting (something he did in ‘Othello’); here, it’s Christie Vela as Friar Laurence.

The good friar serves two awkwardly conjoined plot functions: He offers the immediately ignored, canonical wisdom about passion and restraint (“Love moderately, long love doth so”) and then makes that advice futile by bungling the delivery of the all-important note explaining Juliet’s faked death.

But with a woman in this role, the good friar gains emotional weight, earns more of our attention. Vela’s Laurence is more of an involved, warm, maternal presence — she now offsets the nattering, comically useless Nurse (Liz Mikel) and, in this case, Juliet’s own absent mother. Ferrell’s stripped-down casting has axed both female parents from the Montagues and Capulets, leaving only an abusive Chris Hury as Daddy Capulet. As the single responsible adult female, Vela’s Laurence becomes an emotional, moral counterweight to the Capulet warlord and the two families’ strife and rage.

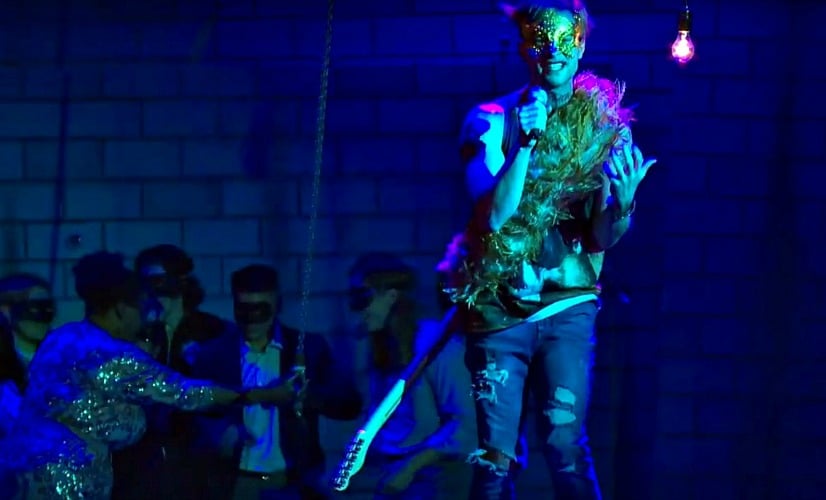

Quick: ‘Romeo and Juliet’ or ‘Hedwig and the Angry Inch’? Drew Foster delivering Mercutio’s ‘Queen Mab’ song at the Theater Center.

But what’s more typical of this production’s sensibility is designer John Coyne’s set. It looks bewilderingly like an empty city reservoir. Whatever its metaphoric meaning, the cistern’s high, curved back wall provides seating for young audience members onstage. They even get to don masks, climb down and party with the Capulet family in the ball where Romeo and Juliet first meet (it’s an easy way for the theater to fill the party scene by padding out its 10-member cast).

All of this — and the DTC’s signature technique of actors-doing-calisthenics-in-the-aisles — makes ‘Romeo and Juilet’ something different, it generates a little frisson, creates an ‘experience.’

But I’d argue all this misses the point because the fundamental idea — dress up Shakespeare in sneakers and Berettas and the young’uns’ll love him — is flawed. Consider ‘The Game of Thrones,’ ‘Lord of the Rings’ ‘The World of Warcraft’: There’s nothing contemporary-looking about any of these. They’re dense, pseudo-medieval fantasies. They’re multi-episode sagas, self-contained worlds with their own languages, governments and even cosmologies — in short, they’re all the kinds of things that make Shakespeare so alienating. Yet young audiences swarm to them in the millions.

In contrast, when Ferrell applies all his devices and upgrades to Shakespeare — including a show-off bullet-to-the-head to round off things at the end — the overall effect is of strain and self-consciousness, of trying too hard. You know, trying to get hip with the kids.

What does engage people at the Theater Center is Ferrell’s casting of Romeo. Jake Horowitz is not the typical teen heartthrob. He’s charming and awkward (once Romeo gets past his unpleasant, pouting-after-Rosaline mood at the start). He’s more like Jay Baruchel.

Chrstie Vela as Friar Laurence, center, Chris Hury, seated left, as Capulet.

You mean the guy from ‘Man Seeking Woman’ on TV?

Horowitz has got much the same gawky, goofy physicality. In the famous balcony scene, Romeo brags that Juliet’s love alone makes him dare to sneak into the Capulet family home just to see her (“Thy kinsmen are no stop to me”). But Horowitz delivers the lines with an over-eager, nervous quaver in his voice. Even the clumsy set — a wall flips up like a garage door, creating an unstable-looking ledge for the two lovers — actually helps in this instance, underscoring Horowitz’ awkwardness (Um, is this thing safe? How do I climb on to it?)

Directed by Ferrell, both Horowitz and Kerry Warren — who has a good mix of innocence and high spirits as Juliet — actually get chuckles in the scene. That’s what makes it fresh and contemporary — unlike the Luhrmann film which devolves into what Hollywood does, showing pretty people kiss. Horowitz and Warren add a layer of credible, adolescent angst and vulnerability. And that’s much harder to do than re-arranging the seats onstage.

Forget that, forget the guitars and the chrome-plated gun. Making us feel Romeo and Juliet are real and alive as any blindly oblivious, lovesick teenagers? So when they die, we feel we’ve really lost someone? That’s how you engage an audience.

Young or old.

Thanks, Jerome.