Review: Lawrence Wright’s ‘God Save Texas’ – Take A Trip Around The State Without Leaving Your Reading Chair

ArtandSeek.net June 7, 2018 63For many years, when friends moved here, I’d visit Half-Price Books to grab a couple of welcome-to-Texas gifts. This was before bookfinder.com, so like some hunter-gatherer, I’d roam among the bookshelves, rummaging for old copies of Larry McMurtry’s ‘In a Narrow Grave’ or ‘Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen.‘ The two essay collections are reflective, historically-informed and entertainingly jaundiced; they’re field guides to the strange history, peoples and customs hereabouts.

Although ‘Grave’ came out in 1968, many of its insights still have a serrated edge: “Most of what I have said about Houston’s pretensions could simply be repeated for Dallas. Houston is open, an opportunist’s delight. Dallas is cleaner than Houston; cleaner because more tightly controlled.”

Still, it’s undeniable some observations in ‘Grave’ have been bulldozed into irrelevance by a half-century of colossal urbanization, immigration and whatever ‘Texas chic’ happens to be this year. But then in 1999, in “Walter Benjamin,” at the age of 60, McMurtry felt the need for a cultural and autobiographical summing up, a look around the landscape and history that had been his subjects (some might say targets) for so long: “In the West, lifting up one’s eyes to the heavens can be a wise thing, for much of the land is ugly. The beauty of the sky is redemptive; its beauty prompts us to forgive the land its cruelty.”

A chief reason many such declarations still stand is that McMurtry was often measuring Texas Present against Texas Past and Texas Myth. He’d been an unhappy child of cattle ranchers, and he used that real-life toehold in pioneer Texas history to evaluate where we were and how we got here.

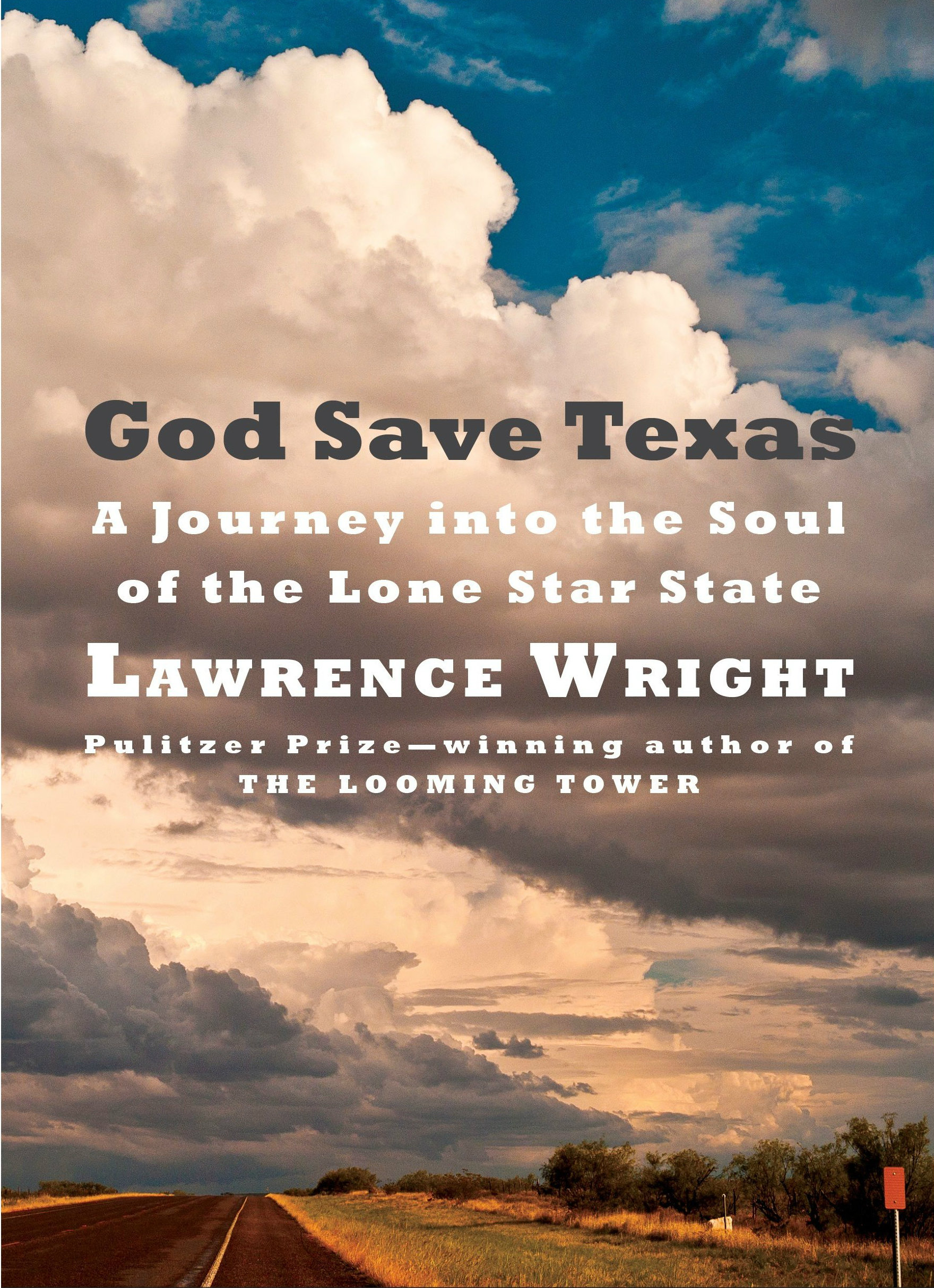

That skeptical look back is a marked difference with Lawrence Wright’s new assessment of the state, ‘God Save Texas: A Journey into the Soul of the Lone Star State‘ – which is a heartfelt but decidedly uneasy look forward. The Austin-based journalist and screenwriter, author of ‘The Looming Tower,’ hikes and bikes along some of the same trails McMurtry did (both ‘God Save” and “In a Narrow Grave” visit major cities: Dallas, Houston, Austin).

Wright does include a fair amount of history in his account of our merry, petrol-pumping Eden (Stephen F. Austin, Spindletop, Hollywood, Charles Whitman). But what motivates ‘God Save Texas’ is Wright’s fear that Texas has been the harbinger for – too late! – what’s already taking over the rest of the country. We know the drill by now: political extremism and paralysis, a roaring nationalism and fear of immigration, a rollback of federal oversight on the environment, banking, education, racial and gender equality, employer liability – and so on.

Meanwhile, many pundits have posited California – environmentally-sensitive, gender-neutral, Silicon-Valleyed and celebrity-cultured California – as the opposite model for the kind of America we supposedly want to be. For his part, Wright worries that in this wrestling match between the two states, Texas plays the posturing bully. We’re arrogant and fearful, certain we’re surrounded by enemies. This justifies both Texas lashing out and crowing over any victory, real or imagined. Open Carry for gun-owners. Rejected federal spending for expanded medical care. Healthy corporate growth in a low-tax, low-safety-regulation business climate.

Wright sketches in this red state v. blue state analysis, but his basic argument is that it’s too binary, too simple and too harsh on Texas. He finds plenty to love and admire in our state. And it’s not just the usual, awe-inspiring features of the Texas landscape like Big Bend or Willie Nelson. As he bicycles and drives around the state, Wright hopes to find Texans who aren’t the loud and intolerant cliches his Eastern friends fear.

Wright grew up in Dallas – and wrote about it (‘In the New World’ from 1988). He contemplates the tragedies tied up with political violence that have scarred the city (JFK and the July 7th police massacre). But Dallas takes some deserved hits from him as well. Income inequality is lower here than in other big cities, for example, but when income inequality is connected to race, the disparity becomes a canyon. Around the country, Wright notes, the average number of African-Americans among the homeless population is 40 percent. In Dallas, it’s nearly two-thirds.

Despite Wright’s Big D credentials, ‘God Save Texas’ is a thoroughly Austin-eyed view of the state. The sizable center of the book concerns insider politics, Texas-grown presidents and the state legislature (topics McMurtry mostly just snorted at). Wright confesses he found George Bush likable – a case of what’s been dubbed ‘Bush Nostalgia’ – given that Bush, as Texas governor, at least attempted to lead from the middle, even though it was Lt. Governor Bob Bullock who was pushing the bills through and keeping the restive legislators in line. Wright repeatedly wishes that, as president, Bush had never invaded Iraq and would like to believe that, otherwise, he’d have been a decent leader (‘otherwise’ in this instance means ‘not fully addressing whatever Bush’s responsibility was for the near-collapse of the economy’).

Where Wright really gets into his Diogenes-like search for a More Sensitive, Middle-Ground Texas is his backstage account of the most recent legislative session in Austin. In this drama, Speaker of the House Joe Straus played the Last Sensible, Business-Minded Republican, one who mostly out-foxed Lt. Governor Dan Patrick’s angry social conservatives demanding crackdowns on the border, abortion and transgender bathrooms.

Then Straus promptly announced he wouldn’t seek re-election.

So we remain a state run by a government that leans seriously more rightward than its population does. (Wendy Davis: “Texas is not a red state. It’s a non-voting blue state.”) Wright sees our refusals to properly fund education and healthcare as seriously retrograde – especially for a state, he argues, that was born optimistic and future-oriented. We Texans seem to be a hearty bunch of can-do-ers who apparently haven’t figured out that an independent-minded, tech-savvy state won’t be built by poorly-educated serfs who can’t afford to see a doctor.

As for Texans not being the cultural Barbarians on the Brazos everyone thinks we are, Wright spends a chapter or so doing quick drive-bys on Texas high art. Look, there’s the Kimbell and the de Menil. Cormac McCarthy and John Graves are just great. Wasn’t artist Donald Judd a bit of a cranky purist with all his minimalist boxes parked around Marfa?

Wright spends far more time on local music and movies (Austin . . . again). Which, frankly, he probably should. If I can crib a line from poet Robert Pinsky, which he used about American culture in general: Texas’ lasting influences lie not in our attempts to ape Europe’s aristocratic masters. They lie in our bastardized arts and bad habits. All honor to the Horton Footes, Donald Barthelmes, Sandra Cisneros and Vernon Fishers of the state, but Texas’ unique contributions are in Western swing, Texas blues, Tejano and T-Bone Walker’s guitar sound. We invented the frozen margarita and the silicone breast implant. We helped launch neo soul (thanks, Erykah), the regional theater movement (Margo Jones in Dallas, Nina Vance in Houston) and the Dirty South in hip-hop. The disreputable genre of the low-budget, high-shock-content indie horror flick took off because of ‘The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.’ This is the state where nachos and the ATM were born, where Tex Avery dreamed up Daffy Duck.

Wright would call such statements “Level III” thinking – a re-appreciation of the kind of homegrown, make-do, “Level I” culture people often learn to escape or scorn. “Level II” thinking is your standard, cultural insecurity and snobbery; it’s borrowed and nouveau riche. For all its faults, Level II has a lot going for it. It did bring us that considerable art collection in Jerry Jones’ football palace, for instance. And put a Michelangelo in the Kimbell.

The not-so-simple fact is that Texas culture is unavoidably what it is because of the state’s crossroads location, its size and its history. Texas is an ongoing collision of Hispanic traditions, a mythic cowboy image of resilience and honor, swaggering pirate capitalism and funky African-American ways. For better and worse, our home state is basically America with the brake cables cut.

So. Never a dull moment around here. Actually, fifty years ago, McMurtry feared Texas was becoming dull. He thought Texas was akin to the younger sibling of California, not its rival but the punk kid brother always trying too hard, trying to look cool in his borrowed Ray-Bans. But then, McMurtry was writing when the state’s population was running away from its rural roots and becoming overwhelmingly urban. What distinguished us – all that struggle and squalor, wildcatters and longhorns – has led mostly to copycat skyscrapers and more freeway exits. We’ve been turning into a suburban industrial park like everywhere else.

So. Never a dull moment around here. Actually, fifty years ago, McMurtry feared Texas was becoming dull. He thought Texas was akin to the younger sibling of California, not its rival but the punk kid brother always trying too hard, trying to look cool in his borrowed Ray-Bans. But then, McMurtry was writing when the state’s population was running away from its rural roots and becoming overwhelmingly urban. What distinguished us – all that struggle and squalor, wildcatters and longhorns – has led mostly to copycat skyscrapers and more freeway exits. We’ve been turning into a suburban industrial park like everywhere else.

Wright’s worldview, on the other hand, is thoroughly post-suburban. He’s trying to find what still distinguishes us – if anything. He does encounter decent folks, talented artists, wised-up activists. But are they … enough? In effect, the questions Wright contemplates are: What’s still Texas – and is it worth it? Yes, of course it is, you’ll say. But remember, one thing that certainly distinguished Texas is that it’s a state born out of a fight for liberty – led by slaveowners. That marks a place, and a people.

Granted, it’s not fair to compare McMurty and Wright. For his part, McMurtry is a superb essayist but definitely not a reporter. He barely interviewed anyone. With ‘God Save Texas,’ Wright wants to be a wise essayist but remains what he’s mostly been: a keen reporter. That was the case with both ‘The Looming Tower,’ his landmark history of al-Qaeda, and his expose ‘Going Clear,’ which bravely took on the deep-pocketed Church of Scientology. Even today, Google Wright’s name, and the first thing to come up is an attack ad paid for by Scientologists. This is five years after ‘Going Clear’ came out. That’s a badge of honor for a journalist.

In 1980, Wright moved to Austin to write for ‘Texas Monthly’ – which is not too long after I arrived in town. That sentence, by the way, is a very Wrightian entrance to a subject. He often name-drops a famous friend or an accolade to illustrate some cultural shift or a personal life change. In ‘God Save Texas,’ we learn that Wright’s Austin neighbor was once director Terrence Malick (‘Tree of Life’). Another time it was Matthew McConaughey. With proper reverence, Wright has held Trigger, Willie Nelson’s legendary guitar. His visit to Houston, it turns out, was prompted by the Alley Theatre’s world premiere of his new play (it was crippled by Hurricane Harvey, a disaster that prompts some of the book’s most moving passages about the heroic decency of ordinary Texans). When Wright toured Lubbock, his guide was the great Joe Ely. By this point in the book, you’re liable to think, Of course it was. Inevitably, perhaps, they didn’t chat about Lubbock’s cotton crop and the unsustainable drain it’s causing on the Ogalala Aquifer. They discussed Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley.

Because that’s what I’d want to chat about with Joe Ely, too.

In his acknowledgements, Wright says that this book is the result of ‘New Yorker’ editor David Remnick asking him to ‘explain Texas.’ Actually, Wright spends a fair amount of time explaining himself as well. There are musings like the following, as he drives back to Austin one evening: “I thought about how unintentional most of life is. Part of me had always wanted to leave Texas, but I had never actually gone. Sometimes we are summoned by work or romance to move to another existence and for me those moments when there is no reasonable alternative to departure have always been joyful, full of a sense of adventure and reinvention. … Now here I was, on a darkening highway in Texas, with so much more road behind me than what lay before.”

In other words, “God Save Texas” is a memoir – a memoir in miniature. Texas became a mirror for self-reflection – as it often does. Nothing wrong with that. Using your late-in-life regrets to reconsider your country, your state, your art, the entire cosmos: This is a tradition as old as Dante finding himself lost in a dark woods as he enters the ‘Inferno.’ Or Henry Adams worrying about our clattering, 18th-century American democracy as it headed into the modern world.

With such ponderings, it’s the journey, as the saying goes, not the destination that counts. Which is one way of pointing out – no surprise – Wright never fully ‘explains’ Texas. Who could? Robert Caro is spending five volumes just on Lyndon Johnson. There’s one Texan whose tremendous contradictions, greatness and pettiness, crudeness and shrewdness, probably embody the state better than anyone. JFK had us dreaming of equal voting rights and going to the moon. LBJ delivered both. He also got us stuck in Vietnam.

But Wright does deliver something of an apologia pro vita sua. His life, he fears, has been “provincial” in many ways. “I’ve always chosen to remain a step away from the center of the action, which for me would have been in the bustle of Manhattan or the corridors of power in Washington or the bungalows of Hollywood studios. They are all lives that beckoned to me. Each of them might have been more fulfilling than the one I chose. … I have been close enough to those beguiling alternative lives to drink in the perfume of temptation [drink perfume?]. And yet, some maybe cowardly instinct whispered to me that if I accepted the offer to live elsewhere, I would be someone other than myself. My life might have been larger, but it would have been counterfeit.

I would not be home.”

Many authors – many people – lack perspective on their own achievements in life. Mark Twain believed his masterpiece was his lifeless biography of Joan of Arc, not ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ Kafka asked his friend Max Brod to burn all his fiction.

Many authors – many people – lack perspective on their own achievements in life. Mark Twain believed his masterpiece was his lifeless biography of Joan of Arc, not ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ Kafka asked his friend Max Brod to burn all his fiction.

But c’mon. Provincial? Consider: Wright is a staff writer for ‘The New Yorker.’ He’s a ‘New York Times’ best-selling author. He won a Pulitzer Prize for ‘The Looming Tower,’ re-worked it into a documentary film and now re-worked it again as a TV mini-series. He won a National Book Critics Circle Award for ‘Going Clear’ and a primetime Emmy for the TV version. He’s a Hollywood screenwriter-producer. He’s repeatedly adapted his print journalism into one-man shows for himself to star in on New York stages – so much so the ‘Times’ has taken to referring to him as a ‘writer-performer.’

This is not exactly a trailer-park existence. I confess whenever our author worked in a reference to his career or managed to name-drop another celebrity chum, the book became a little hard to read. I was rolling my eyes. Would a Manhattan address have conferred greater significance to all this? I know several New Yorkers whose addresses don’t exactly excuse their lives. ‘God Save Texas’ itself was excerpted in the ‘TLS,’ the Times Literary Supplement, one of the world’s leading revues. The London publication has an unconventional new editor, but it’s still not one normally given to excerpting books about the origins of fracking or who’s buried near Ann Richards. So even literary London takes notice of Wright’s jottings.

‘God Save Texas’ is a sincere and knowledgeable guide to the state (though you might be startled to see Muddy Waters listed as a ‘Texas musician’). And it’d make a good introduction to Texas for the many newcomers who still flock here despite housing values that rival Mars-colony prices. Wright’s volume is more earnest, more up-to-date, though less droll, less literate than McMurtry’s essay collections.

I suspect that means it’s more likely to age quicker. As previously noted, ‘Walter Benjamin,’ ‘Narrow Grave’ and ‘God Save Texas’ are very different books in temperament and purpose. McMurtry contemplates his own life and the history (and demise and persistent mythic existence) of cowboys. Meanwhile, Wright crosses the state and has to consider the likes of Alex Jones’ InfoWars.

But by the end, both authors seek forms of reconciliation with the lives they’ve lived and the larger-than-life state they’ve lived in. It says something about our state that it provokes such authorial insecurities, such personal reckonings. This is Texas as both burden and inspiration. No wonder our authors feel the need to explain it, to make peace with it. It’s like Mom and Dad and that first love they lost.

For better and worse, it’s made these authors who they are.