Review: The DTC’s ‘Twelfth Night’ Is Wasting Away In Margaritaville

ArtandSeek.net April 24, 2019 78The brilliant novelist and critic Angela Carter once mused that it’s hard to imagine being killed by too much fun – “death by tickling, perhaps.”

Carter was distinguishing among ‘fun,’ ‘pleasure’ and ‘delight.’ Fun, she writes, is different from pleasure because pleasure has overtones of the sensual – and therefore, the possibly dangerous. Even “having a bit o’ fun” – the cheery British expression for sex – disengages fun in bed from love, marriage, any larger concern.

“Fun is also quite different from delight, which is a more cerebral and elevated concept,” Carter writes. Delight means something in the world has been illuminated – and lights us up in return. Carter concludes that ‘fun’ is simply “pleasure that does not involve the conscience or, furthermore, the intellectual.” It’s fancy free! Which is why many people feel “it must be inherently trivial.”

Determinedly trivial fun is what’s served up eagerly by director Kevin Moriarty in his current production of William Shakespeare’s ‘Twelfth Night’ at the Dallas Theater Center. The show is occasionally amusing, but there’s good reason it’s been chopped down to 90 minutes without an intermission. This kind of fun wears thin quickly.

‘Twelfth Night’ is Moriarty’s first effort with a great Shakespeare rom-com since he staged ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ to inaugurate the Wyly Theatre ten years ago. A decade on, and the moment we set eyes on set designer Anna Louizos’ marvelously realized beachfront property for ‘Twelfth Night,’ it’s plain that the director’s determination to keep Shakespeare enforcedly ‘contemporary’ and supposedly more accessible remains undimmed.

Let’s go mildly crazy: Blake Hackler, one of the entertainments in the DTC’s ‘Twelfth Night,’ shakes his booty for Nicholas Rothouse and Liz Mikel. All photos: Karen Almond

In interviews, Moriarty has expressed a fear of being boring in the theater. Yet he’s employed the exact same methods with Shakespeare for ten years now: stripping down the script, using a modern setting, adding pop songs (this time, Jill Scott, Billy Joel and Stevie Wonder among others), arming actors with squirt guns, encouraging singalongs with the audience, casting actors non-traditionally and having them run through the aisles to delight us because, look, there’s someone actually running through the aisles during a performance.

In all this, it seems he’s more afraid of Shakespeare’s own words, Shakespeare’s wisdom and humor simply delivered by actors – something that audiences might actually want. This time around, all that’s missing from Moriarty’s go-to techniques is the celebratory balloon or confetti drop at the end. But let’s return to that confetti-less finale later: It reflects one of the director’s more interesting and substantive changes to Shakespeare’s play.

Having been shipwrecked on the Adriatic seashore, Viola (Delphi Borich) asks some passing strangers, “What country, friends, is this?” Their reply: “This is Illyria, lady.” But we know the real answer: “This is Padre Island, babe.” The cut-off shorts, the swaying palm trees, the young people dancing to an onstage band playing Prince’s ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ – all we need are some frats lighting up some blunts.

The point – as it was with Shakespeare, too – is setting ‘Twelfth Night’ in some relaxed and beguiling Other Place, a vacation from the workaday. Louizos and costumer Mari Taylor have worked painstakingly to make this sandy Shangri-La as convincingly real as a plastic lawn chair, a beer cooler and a string of party lights.

If only that much attention had gone into rooting the characters as real, conflicted or engaging human beings, we might feel something was at stake. Something might delight and illuminate.

The latest in Versace men’s wear for the beach: Tiffany Solano DeSena, Alex Organ and Tiana Kaye Blair (l to r) in ‘Twelfth Night.’

To take a few examples: Tiffany Solano DeSena plays Olivia, the countess in charge of this particular Margaritaville. The Lady Olivia is in mourning over the tragic, double loss of her father and brother. But because her sorrow leads her to reject the romantic overtures of Duke Orsino, Olivia is repeatedly described as heartless, even cruel – mostly by Orsino.

And that’s primarily how DeSena plays her – and not for laughs. Or depths. Rarely does she convey that Orsino’s wooing might actually be insensitive, that Olivia is weary from all this death and responsibility. Her servants rightly mock her melancholy retreat from life because life itself is the cure for melancholy. At the same time, though, the countess good-naturedly defends the jests to her sour major domo, Malvolio:

To be generous,

guiltless and of free disposition, is to take those

things for bird-bolts that you deem cannon-bullets:

there is no slander in an allowed fool, though he do

nothing but rail.

Instead of a ‘free disposition,’ DeSena sticks to playing Olivia as almost imperious. Conversely, David Matranga plays Orsino as pretty much your standard, cool dude – and not, as Shakespeare intends from his opening lines, a silly aristocrat swooning around, rhapsodizing about love rather than actually loving a woman.

DeSena’s off-putting Olivia even punches a hole in the story’s romantic logic. Viola’s brother Sebastian (Christopher Llewyn Ramirez) shows up miraculously alive and has a rapturous encounter with Olivia – because long before his arrival she’s been smitten by Sebastian’s twin sister Viola, who – as Shakespeare’s heroines are wont to do – has secretly disguised herself as a male servant. Olivia’s sudden attraction to Viola-in-drag is an emotional thawing that the great Mark Rylance – when he played Olivia in the Globe Theatre production – transformed into one of the play’s main pivot points and an amazing comic turn. Here, DeSena’s amorous reaction to Viola is so tepid, you might miss it.

As a result, when the Sebastian-Olivia romance does come along, it doesn’t feel like it’s much cause for joy. Congratulations, Sebastian, you’ve just won the heart of a rather cold contessa. Good luck with that.

Designer Anna Louizo’s richly detailed set is one of this comedy’s successes – although that makes the ugly green plastic clump underneath the balcony all the more odd. Its only purpose seems to be to hide some lights.

Or consider Malvolio. Alex Organ has a real talent for playing monsters (‘Frankenstein,‘ ‘Othello‘), and he easily adds Malvolio’s prickly officiousness to his repertoire. Malvolio despises the party-loving spongers at Olivia’s house: Toby Belch (Liz Mikel) and Andrew Aguecheek (Blake Hackler). They, in turn, prank him by making him believe the Lady Olivia is secretly in love with him.

‘Fun,’ according to the Oxford English Dictionary, has its origins in the hoax. There can be an element of ridicule in ‘fun’ – as in ‘to poke fun.’ Which is why audiences often feel sorry for Malvolio by the end: He’s the butt of what can seem a mean-spirited practical joke, a case of humor going too far by messing with a person’s vulnerable feelings. Organ plays Malvolio with the stiff physicality and bristling energy of John Cleese’s Basil Fawlty. But for the most part, his Malvolio is just an imperious stick. With Fawlty, there’s frustration and pathos powering his rage. He knows he’ll never escape the second-rate hotel he’s stuck running with his dim-witted staff.

Here, we never really feel why Organ’s Malvolio would so hungrily grasp at Lady Olivia’s love. Kudos to Moriarty for creating the one, little, cleverly invented scene that hints at Malvolio’s inner simmer. He notices the forged love letter from Olivia that triggers the prank because he’s been stuck with picking up the beer bottles and other beach trash left behind by the partygoers. That’s our only glimpse of why Malvolio might resent Belch and Aguecheek: They add to his indignities. Otherwise, he’s just a convenient spoilsport we all enjoy mocking.

Go through the other roles in “Twelfth Night” and repeatedly subtract these kinds of motivations, and the comic humanity Shakespeare puts on display becomes almost skeletal. Ultimately, the characters start looking like they exist to trigger the next plot device.

That’s partly because Moriarty’s cut out any chunk of text he finds inconvenient. Which – rather surprisingly – includes just flat-out killing off Feste, one of Shakespeare’s iconic fools. Several of Feste’s greatest lines remain like faint echoes, parceled out among the onstage musicians, including the clown’s famously wistful song, ‘The Wind and the Rain.’ But Shakespeare’s fools are more than just entertainers. They’re frequently a play’s reality principle. Without that clear-eyed figure embodied here – sometimes joining in the antics, sometimes standing apart warily – the carnival spirit runs free, weightless and pointless: As Feste sings, when he was a child, “a foolish thing was but a toy.”

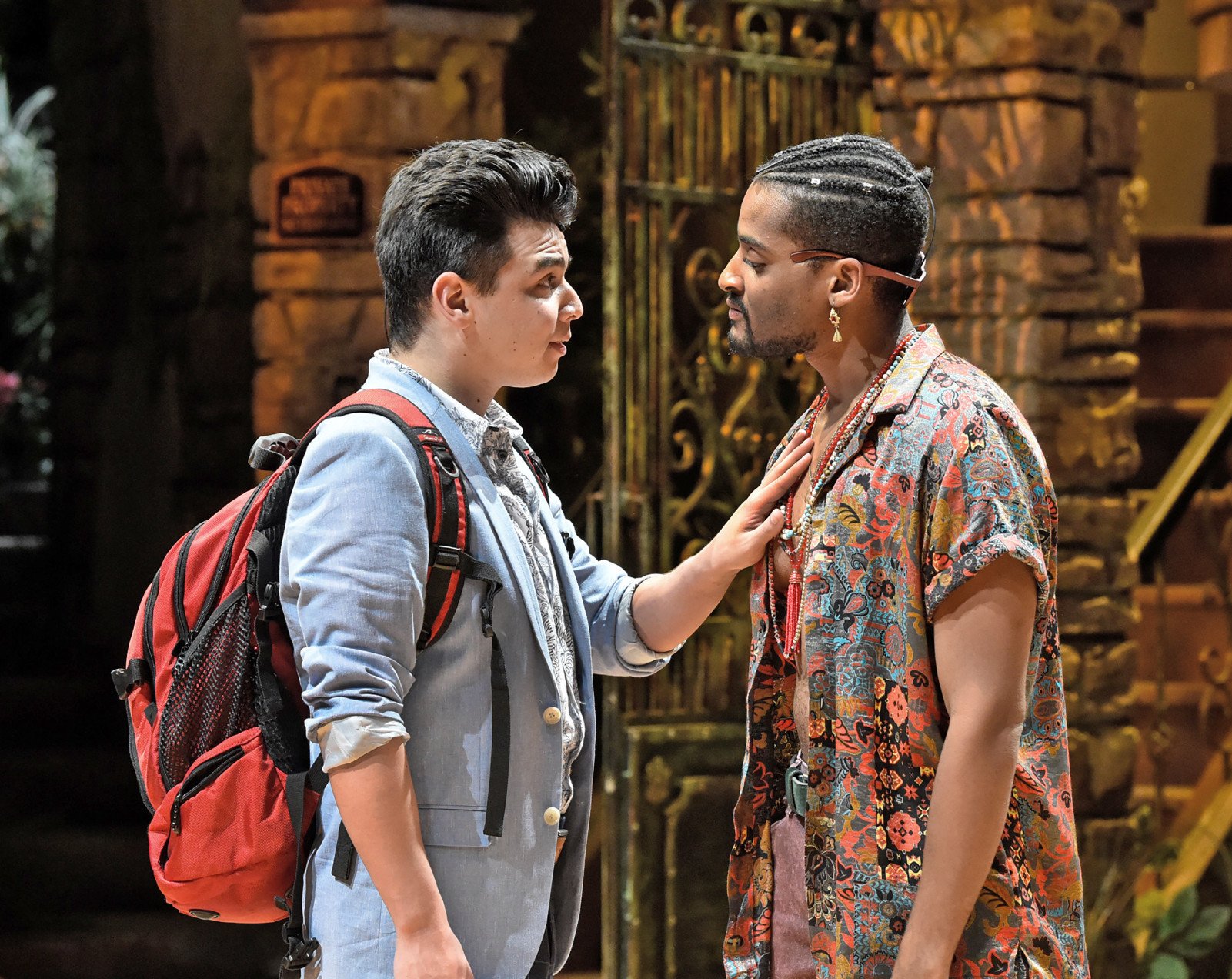

Christopher Llewyn Ramirez as Sebastian and Ace Anderson as Antonio in ‘Twelfth Night.’

In place of all these missing emotions, Moriarty inserts pop songs – taking his cue, as many directors have, from Shakespeare’s famous opening line: “If music be the food of love, play on.” But here, the songes aren’t so much additions to – that is, amplifications of Shakespeare’s intent – they’re substitutions for. Or they’re attempts at substitution, at any rate. When Liz Mikel’s ‘Aunt’ Toby Belch is admonished for being drunk, she responds with outrage and with Amy Winehouse’s ‘Rehab.’ Apparently, no one’s paid attention to the song’s defiant but also self-pitying tone and lyrics: “I don’t ever want to drink again / I just, oh, I just need a friend / I’m not gonna spend ten weeks / Have everyone think I’m on the mend / And it’s not just my pride / It’s just till these tears have dried.”

I know, I know. I sound like the killjoy Malvolio, wagging his finger disapprovingly. It’s not that Moriarty’s ‘Twelfth Night’ is without its real pleasures. Almost anything with Blake Hackler in it is worth watching – even when he’s been oddly cast, as he has been with Sir Andrew Aguecheek. It’s odd because the baseline joke with Aguecheek is that – as his name indicates – he’s too old, timid and sickly to be taken seriously as a potential husband for Olivia. It’s only Toby who encourages this hopeless courtship so Aguecheek will continue underwriting Toby’s drinking tab. Toby goads Aguecheek into challenging Viola-in-drag to a duel in order to impress Olivia with his courage – even as Aguecheek is too puny or frightened to succeed.

With Hackler, this entire comic set-up is seriously shifted because he’s comparatively young and vigorous. Instead of a foolish old feeb, his Sir Andrew is a whirligig of gleeful, clueless energy. When asked to display his dancing skill, Hackler kicks up his heels in delight – like a child showing off how high he can jump. His Aguecheek may be timid but he’s also uncontrollably impulsive – again, like a child. Hackler is the one actor here who should escape through the audience because he’s the one who can get a laugh, using his awkward collisions with seated theatergoers as further revelations of his character’s spirited idiocy.

So the comic shift here is that Hackler’s Aguecheek is clearly a poor choice as a possible husband for Olivia – not because he’s old but because he’s played as stereotypically ‘gay’: dapper, flighty, boyish, sulky, not a “manly” fighter.

But beyond the squirrelishness Hackler finds in Sir Andrew, there’s little richness to these characters – except, interestingly enough, the rather minor figure of Antonio, the sailor who rescues Sebastian, Viola’s twin brother. He assumes a much larger, more nuanced role because Moriarty has strongly emphasized the homoeroticism in ‘Twelfth Night.’ He’s hardly the first director to do so: That Old Globe production with Mark Rylance had an all-male cast, just as Shakespeare’s original ‘Twelfth Night’ did. Even without such a wholesale casting choice, the fluid sexuality in Shakespeare’s comedy is built in: When Orsino has his new manservant, Viola, take his romantic appeals to Olivia, he’s disturbed by how easily his affections seem to shift from their intended target to this attractive young ‘lad’ he’s hired.

But Moriarty goes even further and in a different direction by highlighting the connection between Sebastian and Antonio. There’s actually nothing in Sebastian’s dialogue to indicate any erotic or amorous attraction: He expresses the formulas of gratitude and respect (“I perceive in you so excellent a touch of modesty”). But Antonio speaks much more emphatically, with greater longing: “If you will not murder me for my love, let me be your servant.” And they kiss – an action not indicated in the text; nonetheless, it’s a kiss that has more tenderness in it (on Antonio’s side at least) than all the other dreamy or frantic wooing going on.

And this leads to one of the few truly compelling moments in the whole DTC ‘Twelfth Night.’ Antonio is arrested by the Duke’s men, so he asks the friend he thinks is Sebastian to give him back the money Antonio gave him earlier so he might bail himself out now. But it’s Viola-in-drag, not Sebastian, Antonio’s talking to, so she, bewildered, declines the request. The moment feels genuine because Ace Anderson does something rare here: He plays two emotional notes simultaneously. He’s both angry and tearfully hurt. To him, Viola’s refusal is not simply unkind or disappointing, it’s like a rejection from a lover at the worst possible moment: “I’m breaking up with you, you’re going to jail and I’m acting like all of this doesn’t involve me.” Anderson’s Antonio achieves such sympathetic appeal, such human reality here that, not long afterwards, when Malvolio appears all pouty and sad about how the letter-prank turned out – we barely notice him as he sulks around the theater.

The musicians (KJ Gray, Nicholas Rothouse, Nathan Burke) perform Feste’s ‘The Wind and the Rain’ because now, the fun of this little Mardi Gras is over: “But that’s all one, our play is done.” Sobriety re-asserts itself – with its newfound couples but also its unavoidable demands.

This closing scene is hardly any ‘fun’ at all. But for this fading moment, Anderson does very little yet holds our rapt attention. Alone, he listens to Shakespeare’s words being sung. He contemplatively smokes a cigarette and considers all that he’s lost. He’s completely silent. Yet he’s not boring.