The Cult Of The Cord

ArtandSeek.net December 20, 2018 31Welcome to the Art&Seek Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the cultural creativity happening in North Texas. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists and artworks we’ve chronicled.

The Dallas Museum of Art’s current show, ‘The Cult of the Machine’ features paintings by Georgia O’Keefe and film clips by Charlie Chaplin. But Art & Seek’s Jerome Weeks reports what steals the show is a rolling sculpture weighing nearly two tons. And 80 years ago, when that sculpture was new, nothing on the road could keep up with it. It’s probably the DMA’s fastest artwork – ever.

It’s a car, of course. But – quite the car.

“This is a 1937 Cord Cabriolet, supercharged Cabriolet,” says Mark Ames. “They only built this car for 2 years, 1936 and ‘37. The cabriolet designation really means convertible in today’s parlance.”

Ames is an Arlington entrepreneur who owns nearly two dozen classic autos. This is actually the third Cord he’s owned, but this black, two-seater roadster is his favorite: “I drive it a lot; it’s a joy to drive.”

Ames loaned the car to the DMA for ‘The Cult of the Machine’ exhibition. Ames won’t say how much he paid for it ten years ago, although Cords like it have been auctioned for more than $300,000. That’s partly because there are actually hundreds of different Cords still around, but this model, the 812 – it’s the rarest, the most prized.

“There’s only 12 of these left,” says Ames. “There’s only 12 of these supercharged convertibles left.”

You can tell the supercharged 812 from the standard model Cord because of the chrome-plated exhaust pipes snaking out of the sides of the engine compartment. Only the 812 had them. ‘Supercharged’ means the engine has a forced-air system that causes it to burn fuel faster, run more efficiently. It’s somewhat akin to a ‘turbo engine’ today. Its supercharged V8 engine was why the 812 topped out around 110 mph – making it one of the fastest, factory-built cars at the time. For his part, Ames says he’s gotten his car up to 80 mph, which is fast enough for driving around in a rare masterpiece. The real threat to the car these days, he says, is from people wanting to take a picture of it. With their cellphones. While driving.

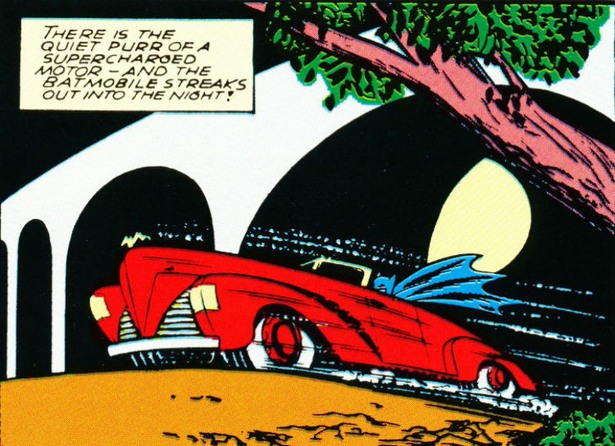

But the primary reason the 812 is valued is its brilliant fusion of design and engineering. The Cord is cited as one of the most striking, innovative cars ever built. Just standing still it projects a sleek muscularity – from its ‘coffin-nosed’ hood and louvered, wrap-around grille to its tear-drop wheel wells. Comic book artist Bob Kane even used the Cord in 1941 as the model for the very first Batmobile.

“It was a great exercise in style,” Ames says. “It was designed by Gordon Beuhrig [who also crafted the Auburn Speedster and the Lincoln Continental Mark II], and that was back in the days before any kind of computers. It was the first car ever designed using a quarter-sized clay model to start. It was all done as a piece of artwork. In fact, there’s a book about the car called ‘Rolling Sculpture.’”

The DMA’s show displays ‘Precisonist’ art from the 1920 and ‘30s. Precisionism was a loose, very American movement. It absorbed European, avant-garde trends – like the sharp, geometric edges of Cubism and some of the impulse behind Italian futurism, which was obsessed with everything fast, mechanical, violent and revolutionary (which is why a number of its artists ended up joining Mussolini’s Italian fascists).

But where the European schools represented radical breaks with tradition – they wanted to ‘force the new’ into being – Precisionism often still looked solidly realistic. That’s partly because the ‘future’ was already here. Precisionism wasn’t so ga-ga for gadgetry because, around the world, America was already seen as ‘the country of the future’: The Empire State Building (1931) was the tallest in the world. The Ford River Rouge Plant was the largest industrial complex anywhere. We’d invented air-conditioning, the Tesla coil, the filing cabinet and the gas chamber. So Precisionism often focused on how the streamlined and the mechanical were already parts of our daily lives. For good and bad.

“America is this vast country and it’s industrializing faster than any other place,” says Mark Lamster about the United States in the ’20s and ’30s. Lamster is the architecture critic of ‘The Dallas Morning News.’ “And so architects are coming from Europe and they’re inspired by the grain elevators, by the bridges, by this American industrial architecture.”

Lamster has written ‘The Man in the Glass House,’ a new biography of architect Philip Johnson. Johnson designed the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth and the Crescent in Dallas. Johnson is important in Precisionism because he curated a 1934 show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York called ‘Machine Art.’ It was revolutionary, the first art show to display mass-manufactured products as if they were one-of-a-kind paintings.

Mark Ames demonstrating the fingertip electric switch that activated the manual gear shift on the Cord 812. Note also the chrome ‘horn wheel’ inside the steering wheel. Photo: Dane Walters

“Designed objects had been in museums before,” says Lamster, “so you’d see like vases and chairs in period rooms showing us a salon at Versailles. But the idea that every day, industrial objects could have artistic value – you know, an airplane propeller, ball bearings, a waffle maker – that was what was being presented as art.”

Which brings us back to the automobile at the DMA. Philip Johnson loved the modern, the sleek, the machine-made. Not surprisingly – Johnson himself owned a 1937 Cord Cabriolet.

Mark Ames can rattle off a list of the Cord’s many innovations:

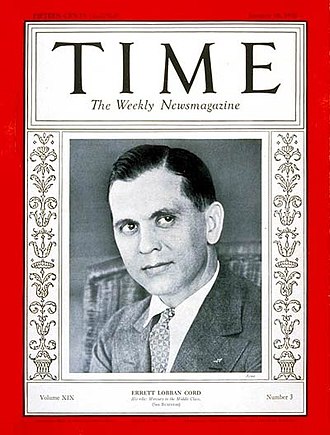

In 1932, Cord owner E. L. Cord (who also owned Auburn and Duesenberg) made the cover of Time.

- It was the first car with front-wheel drive – because of that, it didn’t need the drive-shaft hump that runs down the middle of a typical car. That allowed the Cord to be lower and sleeker than the high-riding carriage-boxes of the ’30s. It also gave the car more foot room, which was needed considering how narrow it is, even for a two-seater.

- It was the first car with a dial to raise or lower the illumination on the dashboard. One of the first to have a built-in radio. One of the first to dispense with running boards – it didn’t need them for passengers to ‘step up’ into the car because it was built so low. The lack of running boards augmented the overall ‘clean,’ streamlined look.

- The first car with a covered gas cap. Not a big deal, yes, but it perfectly suited the car’s aerodynamic aesthetic.

- The first car with an electric switch on the dash to shift gears. The gear box was manual, but the switches meant the driver wasn’t physically shoving the transmission into different gears. An electro-servo did that.

- Beuhrig was a genius when it came to using off-the-rack products to fit the car’s design. Putting a horn button in the middle of the steering column was too costly and cumbersome, so Beuhrig put a chrome metal wheel inside the steering wheel, a wheel that echoed the Cord’s design elements, like its hubcaps and knobs. It also offered the safety and convenience of not needing to take either hand off the steering wheel to honk the horn. Voila, the first horn wheel, standard equipment for years on many American cars.

- Most famously, the Cord 812 was the first car with hidden (or retractable) headlights. You manually opened and closed them with cranks tucked away under the dash. Another sign of Beuhrig’s make-do inventiveness: The headlights are adapted from aircraft landing lights.

So with all these gizmos integrated into the design, just how ‘advanced’ was the Cord? No other factory-built car came equipped with both standard front-wheel drive and retractable headlights for 30 years. And when that new, ‘revolutionary,’ full-size luxury car arrived, the 1966 Oldsmobile Toronado, it had hubcaps with circular holes lining the rim – a tip of the hat to Beuhrig’s own design on the Cord’s hubcaps.

Unfortunately for us at the DMA, Ames can’t fire up his car’s Lycoming V8 engine. Fire safety regulations. When put on display indoors like this, cars are drained of fuel and oil and their batteries are disconnected.

But perhaps standing still like that, unable to move – it’s only fitting. As the DMA’s show on Precisionism indicates, there are downsides to innovation. The Cord was a huge hit with the public. And it more or less killed the company.

“When they first introduced the car,” Ames says, “the response was so great, they got orders beyond their ability to produce. And they had some issues with some of the technology, so they were not able to deliver on time.”

Those issues included vapor lock (the fuel line overheats and the liquid gas vaporizes) and slipping out of gear on occasion. Eventually, E. L. Cord’s Auburn Automobile Company was sold offto the Aviation Company. Officially, it still exists, though Avco, as Aviation is now known, is mostly in, well, aviation: airlines, air fields, air transport.

Today, as a still-functioning antique, Ames’ own Cord does have some of the old-car drawbacks that are true for many vehicles from the era: Brake technology, for instance, hadn’t kept up with a supercharged car’s speed. If you went fast enough and applied the brakes long enough, they’d overheat and freeze up. The Cord also wasn’t designed – as today’s cars are – to sit in boiling hot, bumper-to-bumper freeway traffic for hours. So its engine can overheat – which is why many Cord owners have installed an extra fan in the engine compartment. And the convertible roof is still a complicated, Tinker-Toy operation to get up or down. But the Cord was the first car to have a ‘ roof storage trunk’ with a streamlined ‘lid’ – where the convertible roof retracts out of the way. Again, another stylish touch.

As Ames says, the Cord was like a comet from the future. It burned brightly – but not for long.

We’re lucky to catch one at the DMA.