The Rise Of ‘Sunken Garden,’ The 3D Opera That Crosses Dimensions

ArtandSeek.net March 12, 2018 33A live performance of any opera is already three-dimensional – unless, somehow, the singers and sets have been seriously flattened. But the opera ‘Sunken Garden’ is often called the ‘3D opera’ because of its unprecedented fusion of live (three-dimensional) singers with film performances and (three-dimensional) digital projections. The groundbreaking work debuted in London, Lyons, then Toronto — and now the Dallas Opera is presenting its US premiere.

But ‘Sunken Garden’ also represents the fusion of two unique, but chiming artistic talents.

Sunken Garden – Excerpts from Michel van der Aa on Vimeo.

You may know British author David Mitchell from his best-selling novels, including ‘The Bone Clocks’ and ‘Cloud Atlas.’ The latter one became a visually dazzling but so-so film in 2012 from the director of ‘The Matrix Trilogy,’ starring Tom Hanks and Hallie Berry. ‘Cloud Atlas’ is a sci-fi-ish epic racing through six different centuries, with characters’ lives interrupting and rippling through each other across time. It’s characteristic of several of Mitchell’s novels in that it’s seriously involved with music — in this case, a forgotten classical work, whose musical themes and form somewhat echo the story’s own intersecting plotlines.

In one scene, Hallie Berry, playing a journalist, has tracked down a vinyl recording of the ‘missing’ classical work: ‘This is the ‘Cloud Atlas Sextet?’ she asks a record store clerk, played by Ben Wishaw.

‘I doubt there’s more than a handful of copies in all of North America,’ he says.

‘But I know it,’ Berry’s character declares, even though she’s never heard it before — yet will live out its implications in the past and the future. “I know I know it.’

Hallie Berry in the future in the 2012 film, ‘Cloud Atlas.’ Photo: Jay Maidment.

The 49-year-old Mitchell often uses multiple narrators, multiple dimensions like this. He plays with time and mortality, with power and memory — with narrative itself.

So why can’t he just tell a straightforward story?

“To give it a thoughtful answer,” he says, laughing — on the phone from Chicago, “it can’t be straightforward. It’s a re-phrasing in creative writing terms the question, ‘Why are we who we are?’ It actually becomes harder, as your career goes on — if you’re lucky enough to have a career that goes on — to keep out the motifs you find yourself going back to again and again to kickstart a narrative. I’ve got about five or six archetypal themes. Difficulties in communication. Fissures in time and space. Predation. But why this lot, I’m not sure.”

Mitchell’s musical inclinations and his ‘maximalist’ writing — his way of pushing a story’s many possibilities to the breaking point and then merging them together again — found a receptive reader in the Dutch composer Michel van der Aa.

The 48-year-old van der Aa isn’t famous outside the rarefied world of contemporary international composers. But in that world, he’s a big deal. His 2010 cello concerto called ‘Up Close’ won the Grawemeyer Award. The Grawemeyer is the classical composer’s equivalent to a Nobel Prize. It’s been around for 30 years — and even Philip Glass hasn’t won it.

Composer-director Michel van der Aa (left) and novelist-librettist David Mitchell (right) in ‘Composing Conversations,’ a public discussion held by the Dallas Opera. Photo: Jerome Weeks

“Michel’s an explorer,” Mitchell says of van der Aa’s cross-disciplinary artistry. “And he’s an alchemist. And he’s a grown adult with the sense that he’s a kid in this fantastic magical toy shop.”

He could well be talking about his own approach to writing novels. When the two men eventually met, van der Aa suggested Mitchell call him the next time the author, who lives in Ireland, was in Amsterdam. The next time Mitchell was in Amsterdam, he told his Dutch editor — with typical British reticence — Welllll, maybe he shouldn’t call van der Aa. The man teaches, after all. He’s probably busy.

“I still remember my editor saying in this cold, steely voice,” Mitchell says with a laugh, “‘Now don’t you do his thinking for him. I’ll call him and see if he’s busy.’”

When they did meet, the two men didn’t immediately launch into possible projects. They talked opera: what it could be, what it should be, going forward. And then Mitchell told van der Aa about a novel he’d been considering, part detective story, part diabolical fantasy.

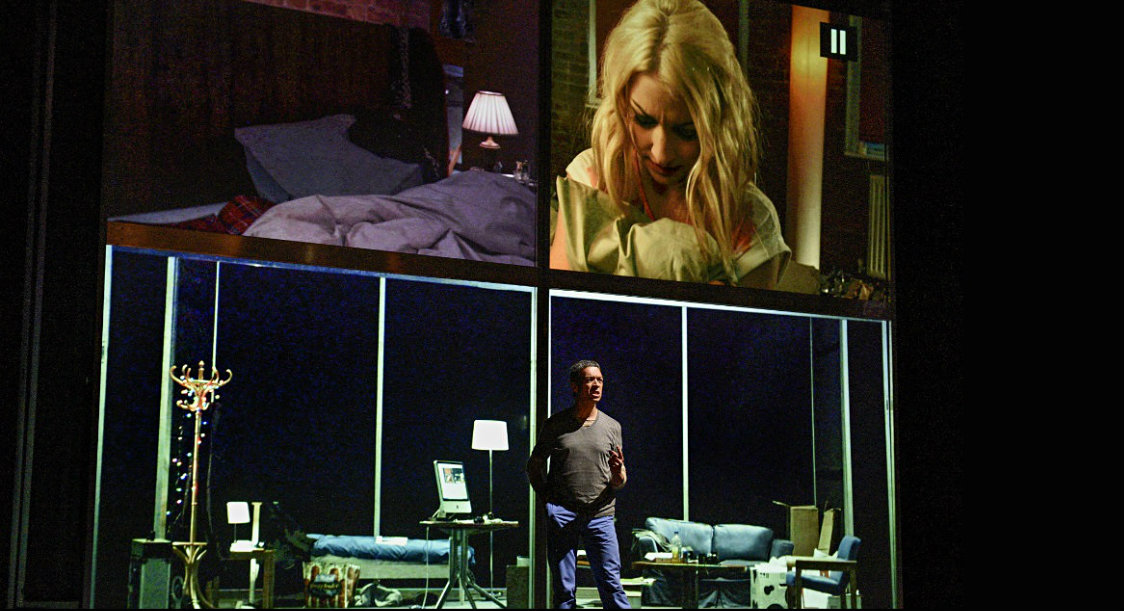

Roderick Williams as video artist Toby Kramer (bottom) and Kate Miller-Heidke as Amber in the video above. Photo: Karen Almond.

In the opera, the story follows a video artist named Toby Kramer, who’s commissioned to shoot a documentary about two missing people, a software engineer and a party girl named Amber. The videomaker encounters a psychiatrist named Marinus who knows more than she lets on (a figure who pops up, in different forms, in several of Mitchell’s novels), and Toby discovers that the two missing people are trapped between life and death in a kind of way-station, an unreal garden hidden under an overpass. There have been videos before this point, but the garden is where the 3D projections kick in and operagoers need to put on their 3D glasses — as we’re told in a pre-show announcement.

Each character reveals past torments that have also trapped them, in a way, in their own lives. Australian mezzo-soprano, pop singer and songwriter Kate Miller-Heidke sings Amber’s role — she’ll appear in Dallas entirely as a virtual figure, not in ‘real life’ on stage — and she sings music that’s also typical of van der Aa’s work: It shifts from electronic dance to pop ballad to operatic aria.

In a public discussion last week hosted by the Dallas Opera, van der Aa pointed out that opera composers have always drawn on folk tunes, popular melodies. “Why not now?” he asked with a smile and a shrug.

Writing the libretto and lyrics for an opera — rather than being some tortuous plunge into a new style of writing, it was almost a relaxing break, Mitchell says. He’d written one opera before, but he admits he still delivered a first draft to van der Aa that would have become something like a four-hour long epic. The novelist filled in every character’s backstory in detail. (‘Sunken Garden’ is now closer to 100 minutes.) But Mitchell ultimately came to see that, unlike with a novel, he doesn’t have to generate all the realistic details that a reader needs to ‘see’ things in a novel, especially when those things are as fantastical as they are in ‘Sunken Garden.’

“It’s rather like writing a fairy tale,” the novelist says. “I don’t have to worry about making it ‘real.’ I can just write ‘Exit garden through a vertical pond,’ and leave it up to Michel and his designers [notably set and lighting designer Theun Mosk] to figure out what a ‘vertical pond’ looks like and how it works on stage. And because ‘Sunken Garden’ has that dark, ‘Alice in Wonderland’ aspect, the 3D is not a gimmick. Making it integral to the story was important for Michel and me.”

Katherine Manley as Zenna Briggs, who commissions Toby Baker’s documentary. Photo: Karen Almond

What’s more, opera – as perhaps the world’s most collaborative art form, using music, video, dance, costumes, sets – opera also has a tendency to ‘max out’ its storytelling, to pile on references and impressive spectacle. Much like Mitchell’s novels.

“It’s somehow an externalized dream,” he says. “It’s a moving mythology. It’s the ultimate art form, isn’t it? It’s like being inside a painting. Pretty much anything that humanity came up with before the 20th century in terms of ways to do a narrative — you can find hefty strands of its DNA in opera. What more can I say apart from a resounding, ‘Amen’ and ‘Hallelujah’?”

Well, he could say what he told van der Aa last week.

He’d like to try creating another opera with him.