These Five Young Men Were Bullied For Being Dancers. Now, They’re Headed To Juilliard.

ArtandSeek.net June 9, 2017 54This fall, five male dancers – all graduates from Booker T. Washington High School in Dallas – are headed to Juilliard, the renowned fine arts school in New York City. Both Booker T. administrators and the college regard it is an unprecedented hallmark.

They say the day they got accepted into Juilliard still feels like a dream.

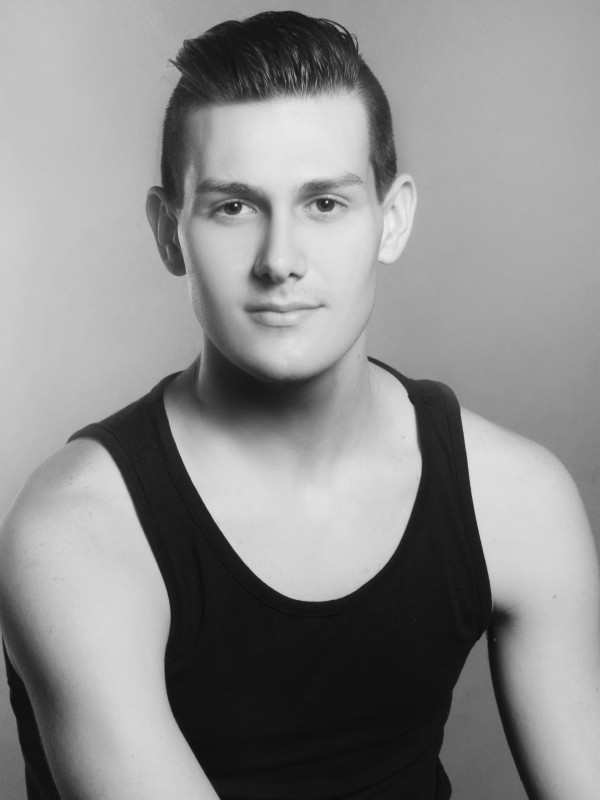

“I dropped my phone. I screamed, and I ran into my living room and started crying,” said Ricardo Hartley.

“I had a mouthful of cereal. I got the call, answered it, and I was choking, trying to swallow,” Zane Unger chimed in.

For Michael Garcia, the moment was sweet relief.

“You receive a call with a New York area code, and you’ve been waiting years and especially since your audition, just anxiously awaiting this phone call,” he said. “And I remember I didn’t cry or scream or anything, I just sat down in silence, and I was like, ‘I just got into Juilliard.’”

Meet the Booker T. Washington Fierce Five

Juilliard accepts only 12 male dancers from around the world each year. Kate Walker, the dance coordinator at Booker T. Washington, said the high school does have a legacy of excellence.

“But it’s really a coup to have as many men from one department,” Walker said. “In 2014, we had four dancers – two men and two women – go to Juilliard. But truly to have five men in one year is really unheard of.”

Juilliard confirmed it’s never admitted that many dancers from one school before. In 2014, the school also admitted an actor from Booker T. Washington.

Each dancer has a unique story. Garcia started dancing when he was 7 years old, and he moved to Dallas from South Texas to pursue it. Hartley was a late bloomer, picking up dance at 13. Unger, once a clumsy baby, used dance to find balance.

“As opposed to using words, I feel like I can use my body language and the way I move to express my thoughts.”

Kade Cummings followed in his sister’s footsteps: “I just tagged along with her, and I got interested watching the classes, and I was like ‘Hey I can do that too!’”

And Todd Baker started dancing when he was 9, after cycling through several other hobbies. Dancing, to him, felt natural.

“It feels natural to me just like it might feel natural to someone else who loves to write or loves to sing,” Baker said. “As opposed to using words, I feel like I can use my body language and the way I move to express my thoughts.”

A journey of struggle and sacrifice

The guys say Juilliard is the ultimate affirmation for young dancers, but getting in didn’t come without struggle. Some of them had financial hardships – sometimes weighing whether to pay for dance classes or pay for another meal or two. Both Hartley and Garcia uprooted from their hometowns to study dance in Dallas. For Garcia, it was tough to dance freely back in South Texas, where he said Mexican culture discouraged it.

“Dancing was just something little girls did as a hobby,” he said. “I think my mother was worried about what other people would think.”

Garcia is not alone. Male dancers continue to face stigma that challenges their masculinity.

“At least for the five of us, I’m sure there was a point where all of us went through that teasing and that bullying and thought, ‘is this really something I want to do for the rest of my life? Is this something I want to deal with for the rest of my life?’” he said.

For Hartley, that conflict was even closer to home.

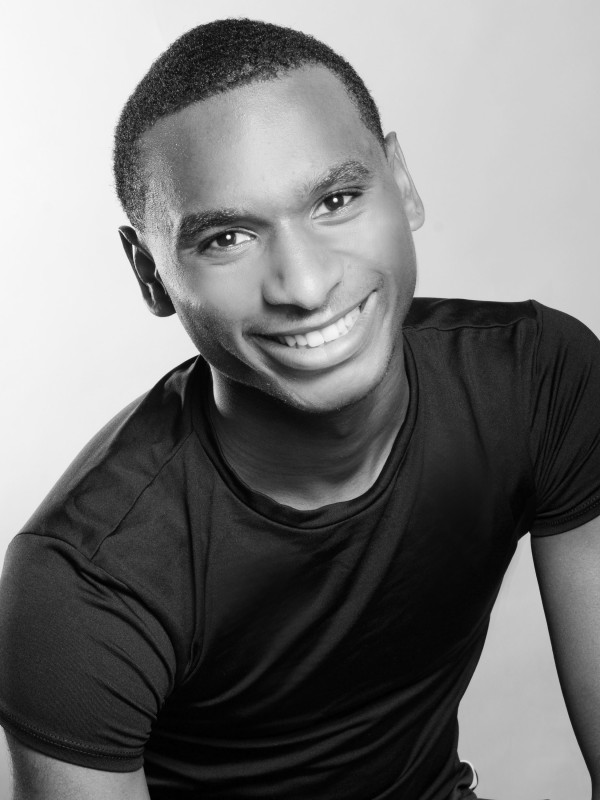

“My father had the biggest problem with it,” Hartley said. “You don’t see a lot of male dancers, and so it came to the point where my dad hated it so much, my dad would make me late to rehearsals. He wouldn’t take me to dance class.”

He said that relationship helped him realize that going to Juilliard means much more than just an education.

“For me to say that a black man who started dancing at a late age can make it this far and can keep going, it’s like I can be an inspiration for other black kids,” he said. “It just feels unreal in that my voice is finally being heard.”

The guys said they weren’t the only ones who struggled. Unger said while he’s worked hard and given up plenty to get to this point, his mother made the real sacrifices.

“She waited outside for dance classes for hours on end, she pays for literally my entire career so far, and she’s just always there for me,” he said. “I think our parents made the sacrifice just as much as we have, and without them, we would not be here.”

“It just feels unreal in that my voice is finally being heard.”

For Garcia, things with his mother took a turn.

“This past year, I developed a really horrible relationship with my mother, and I realized that for me to be able to continue down this path and thrive like I want to, I needed to remove myself from that relationship,” he said.

Since September, he’s stayed with friends and relied on the generosity of their families and his teachers. He hasn’t spoken to his mother. He hasn’t told her about Juilliard, but he assumes she’s caught wind of the news by now.

“I hope she’d be happy for me. It was a goal we’d set together a long time ago.”

But he, like the other four, are looking forward. The big move to the Big Apple is just a summer away, and there’s not a nerve in sight.

They’re excited about New York: the food, wandering around Soho. Mostly, they’re thrilled to be in a city where they can be themselves, and where they believe dreams come true.