Working In Black And White

ArtandSeek.net July 19, 2018 37Welcome to the Art&Seek Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the stories and artistic efforts being made by creatives in and around North Texas. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

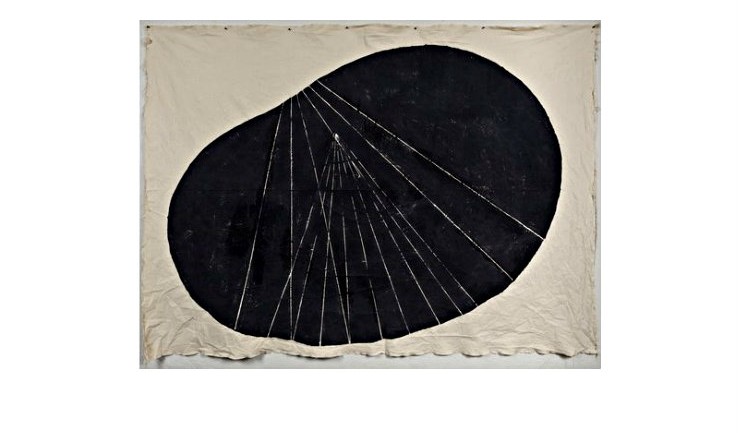

‘Been Knowin’ Since ’93,’ graphite and cloth, 2017

You can’t get much simpler than the materials Denton artist Taylor Barnes often uses – just black charcoal on white fabric. Or tree branches and twine. In this Art & Seek Spotlight, we visit Barnes’ studio to see how much she can do with so little.

It’s an unusual studio on the UNT campus. Barnes’ studio is admittedly a bit of a mess; most artists’ studios are. Messing around is often just part of the creative process. But here, everything’s pretty much black or white. A fine black powder coats the floor, it’s like the darkest soot imaginable. And it’s smudged across the once-white walls.

Barnes must create a lot of dust in here.

“Oh, it’s ridiculous usually,” she says. “I mean, this is me cleaning. But this room is usually coated, yeah.”

The 25-year-old Barnes often works in charcoal – not the kind you light up in your backyard grille. Barnes uses willow charcoal, burned tree branches that are turned into what look like sticks of pitch-black chalk. It crumbles into powder pretty easily, especially when it’s rubbed across a textured fabric like duck cloth canvas. She uses a bit of fixative – a sprayed glue – to hold the charcoal to the canvas, but not a lot, not enough to lose that thick, dusty, you’re-going-to-leave-fingerprints texture of charcoal.

“It’s the tactileness of it, the texture that comes up on the canvas,” she says of the charcoal. “I’m really just attracted to how black it can get.”

The artist in her studio. Photos: Courtesy of Taylor Barnes.

And with Barnes, it gets densely dark. She works that charcoal. Which is why she uses a face-mask respirator when she’s here, like a house painter. So she can breathe.

“Whenever I started working in here and I was like seeing all the flakes going up, I thought, ‘Ohmigod, I’m gonna have to protect myself from this.’ It will kill me one day,” she says with a laugh.

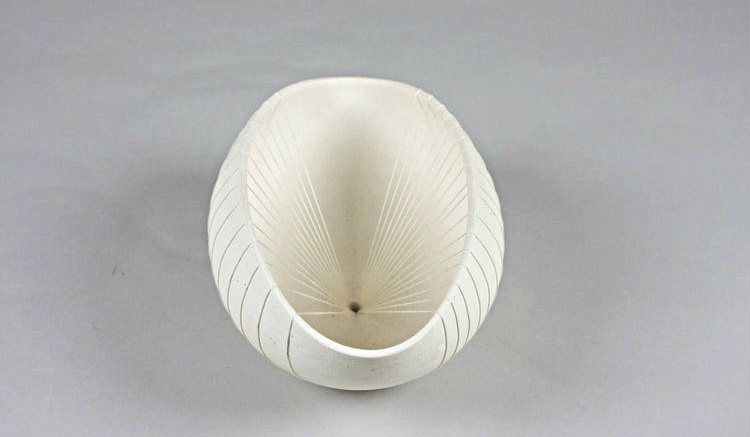

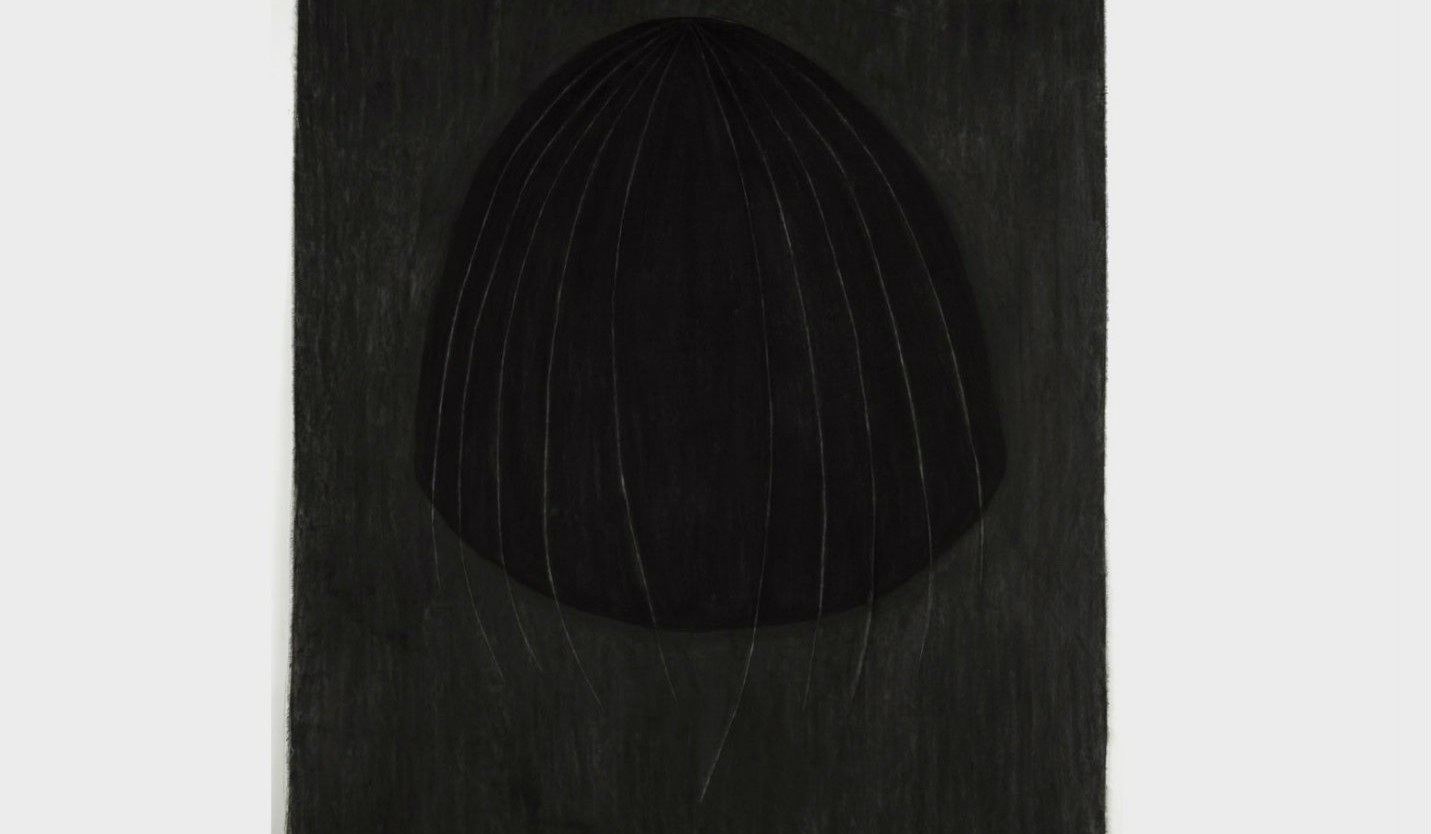

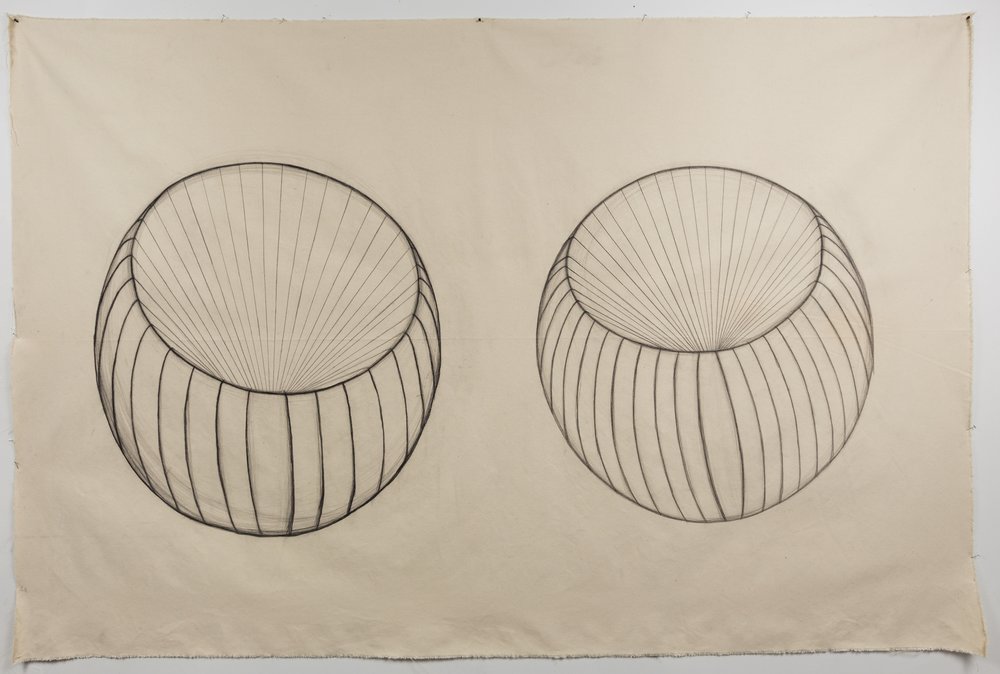

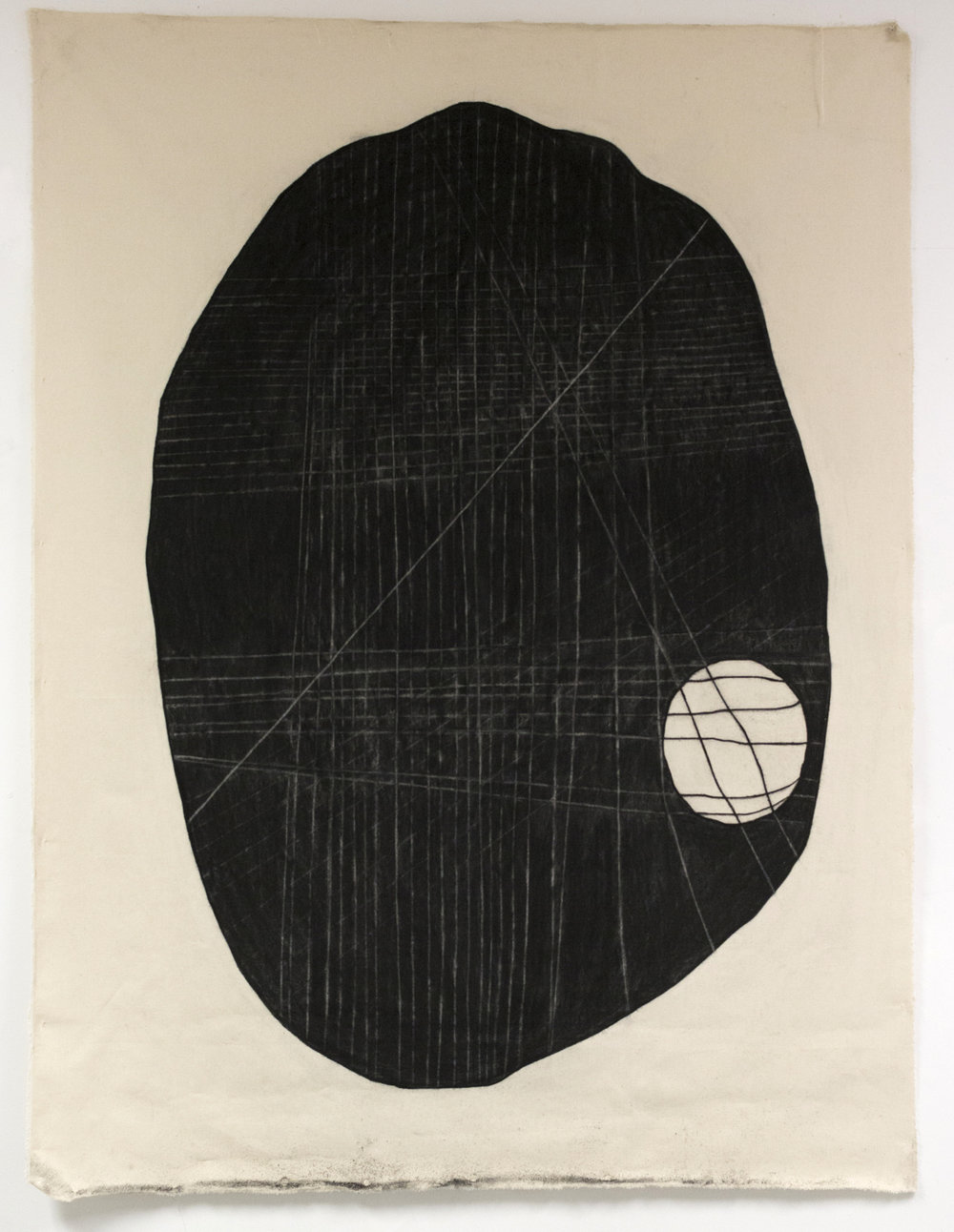

Many of Barnes’ current works are both impressive and restrained in their stark simplicity. On loose, bare fabric, she creates huge, dark circles and ovals – they look like black holes on the wall. But these 2-D works recall her work in 3-D as well. Barnes has made handsome, ceramic bowl-shaped sculptures. They look like elegant dishware you could buy at Crate and Barrel. And they, too, are either black or white.

“I love that there’s no frills,” she says. “It’s just black and white. I love that about it, yeah.”

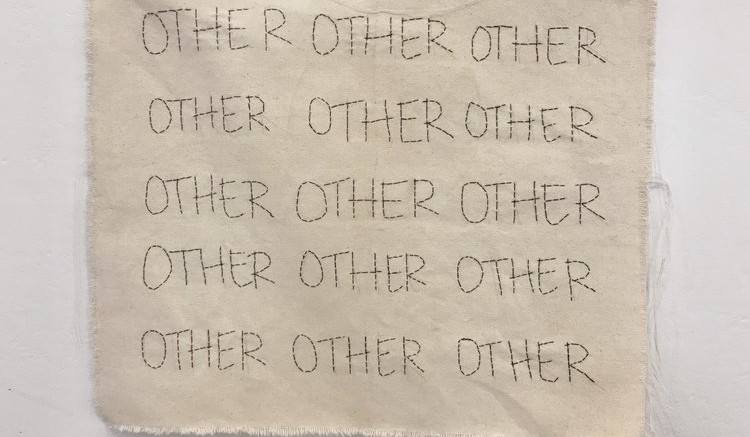

Other times, Barnes will take a word – like ‘other’ and embroider it into fabric – over and over. Or she’ll print the word “token” in black on plain fabric – over and over. Or she’ll build a simple cage of sticks and twine and call it ‘Barracoon’ – an old term for a slave barracks.

Barnes is African-American. She’s one of the very rare black graduate students in UNT’s College of Visual Arts and Design. So yes, you can be impressed by the incredible minimalism of Barnes’ artworks – and not know that all this is about race.

“That’s what makes her work so powerful,” says Lauren Cross. She’s an artist and teaches interdisciplinary art and design at UNT. “She is having this very intimate conversation about race, about her own experience of being African-American, and yet the visual representation of it seems simple yet has all these different layers.”

Barnes grew up in Dallas, attended Coppell High School, but not as the typical budding artist, although art was a side interest.

“I was a really huge jock,” she says, “like I played soccer, I played tennis for a really long time, I was like super-competitive. And then I tore my Achilles – so I started taking art a lot more seriously.”

‘That Thing You Said Still Eats At Me,’ charcoal and cloth, 2017

Barnes started in ceramics but ended up double-majoring at UNT in fibers and ceramics. Her work’s been shown in local galleries like Erin Cluley and 500X; it’s won awards. Barnes says art is where she finds her calmest self. It’s where she transmutes her experiences of race and identity into fabric, clay or wood.

“I don’t think every black artist has to talk about black things,” she says. “I don’t think that is fair because we live it every day. But I definitely think it’s important.”

At Coppell High, Barnes says, white students called her ‘oreo’ – meaning, of course, black on the outside, white on the inside.

“And what do you do or say when you’re 12-14 and you don’t understand what that means or what that comparison is?” she asks. “So I have no clue what provoked that. I guess because of the way that I speak because I have an education.”

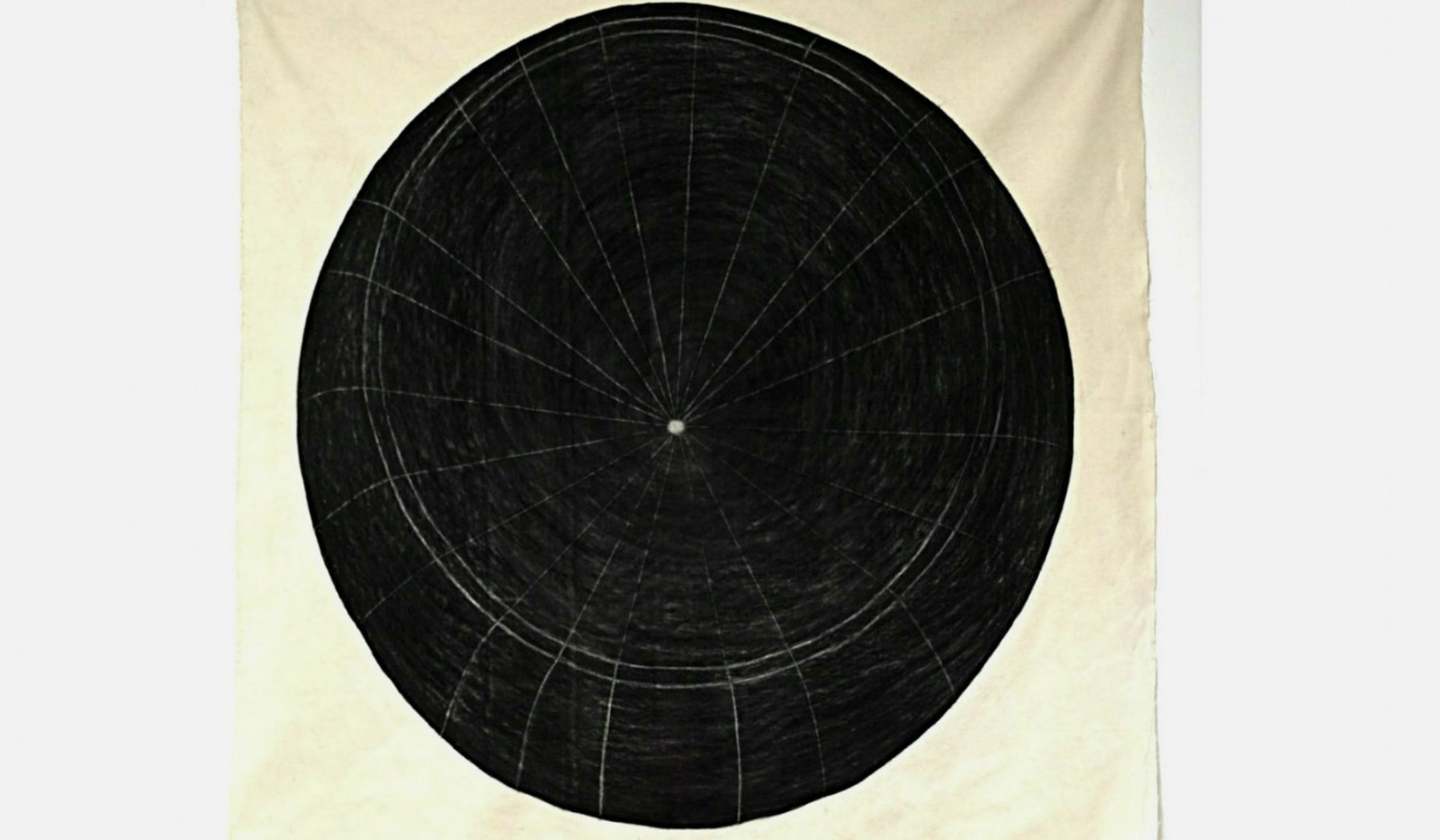

What Barnes ultimately did was title one of her works ‘Oreo.’ It’s a huge black circle with fine white lines giving it shape – only the title indicates there’s something more here. Barnes is taking minimalist forms, which are typically abstract, even emotionally blank, and she’s layering in racial history and personal experience. She isn’t bothered by the fact some people catch these meanings while others may see only shapes.

“I think that’s a great place to be because there’s no barrier, and there’s no box. And to me this theme of identity and experience will be a common theme in my life. This is who I am, so it doesn’t feel forced.”

So Barnes expects to spend her lifetime using charcoal, clay, fabric and other materials, to explore her complex feelings about race — because black or white, they’re not so simple.